Red River of the North - Fargo-Moorhead Diversion

| Geolocation: | 46° 53' 16.6571", -96° 44' 17.2851" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | .220220,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 10001,000 km² 386.1 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Continental (Köppen D-type) |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | urban |

| Important Uses of Water | Domestic/Urban Supply, Fisheries - wild, Recreation or Tourism |

Contents

[hide]Summary

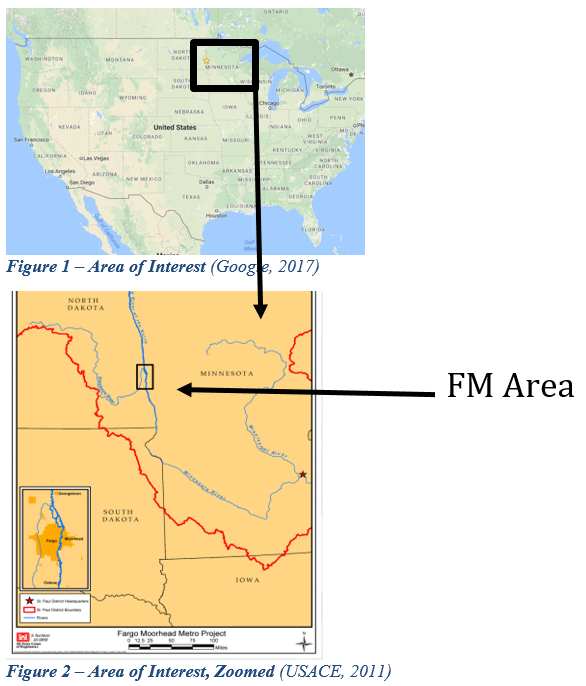

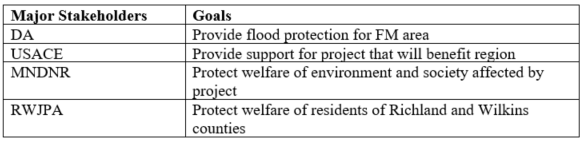

The Fargo-Moorhead Diversion (FMD) has been proposed as a solution to flooding in the Fargo-Moorhead (FM) area of North Dakota and Minnesota. The project is aimed to reduce the risk of flooding from the Red River of the North (RRN) which flows through the FM area, directly between the cities of Fargo, ND and Moorhead, MN, and acts as the ND-MN border. The RRN has reached the defined “flood stage” a total of 48 times in the last 109 years, and thus presents nearly bi-annual risk to both communities, which comprise in total of roughly 220,000 people. This project is ongoing, but is currently in litigation over certain disputes from the opponents. If litigation is resolved in the next year or does not halt construction, then the project is scheduled to be finished in roughly 2022. The city governments of Fargo and Moorhead have partnered with the local county governments to form the “Diversion Authority” (DA) which itself has joined with the United States Army Core of Engineers (USACE) to propose a US $2 billion project (FMD) that would divert water around the cities and prevent major flooding during a flood event. However, there are those that oppose the diversion. These opponents include the Richland-Wilkin County Joint Power Authority (RWJPA) which is comprised of a pair of two counties upstream from the FM area on the RRN, and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (MNDNR). Both the RWJPA and the MNDNR claim that irreparable harm will be done if the project is carried out and thus have filed suit against the DA and the USACE attempting to halt the project construction.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

Geographic

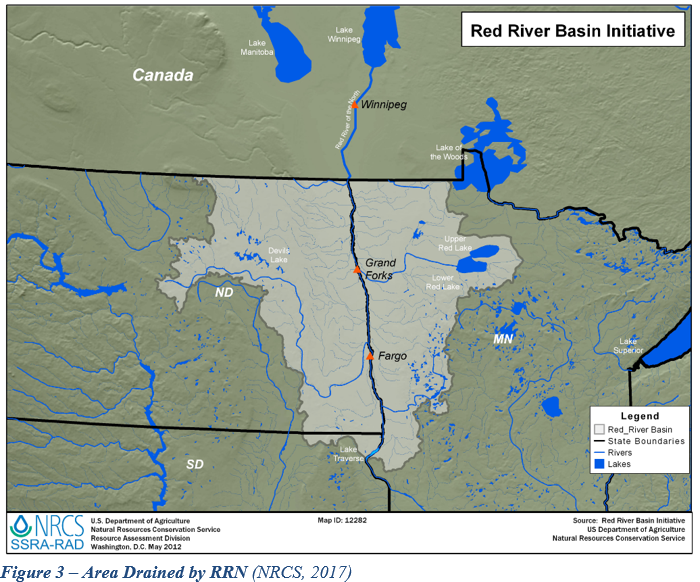

The RRN is situated in the Red River Valley which runs north and south along the Eastern and Western borders of North Dakota and Minnesota respectively, north into Canada, and eventually drains into Lake Winnipeg in Northern Canada.

Along with making up the border of the two states, the RRN also drains a large area of Eastern North Dakota and Western Minnesota, with multiple small streams and rivers running into it as it flows north. The Red River valley is a very fertile area that supports a large amount of agriculture into both MN and ND. The rich soils and flat topography support a productive environment. For example, the US is the 3rd largest producer of sugar beets in the world, producing roughly 10% less than the world’s leading producer, Russia (World Atlas, 2017). An average of 57% of US sugar beet acreage is planted is in the Red River Valley (USDA: Economic Research Service, 2017). Yet the flat topography has the effect of exacerbating any flooding that occurs meaning that the cities and towns in the valley, which are very similar in elevation above sea level, have a similar level of risk when it comes to flooding issues in the valley. However, due to the nature of past settlement, the valley is home to ND’s largest population centers (Fargo and Grand Forks) as well as the largest in western MN (Moorhead).

Historical

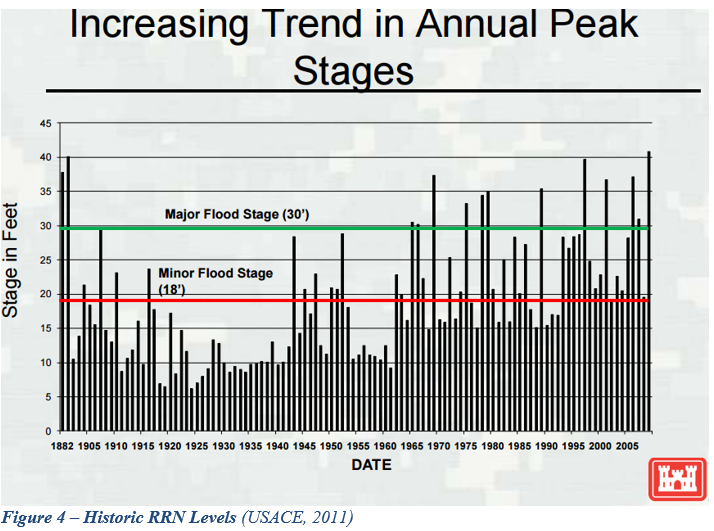

The RRN has a history of flooding. As mentioned previously, it has flooded 48 times in the last 109 years (USACE, 2011) . For the RRN flooding is defined as a measured water level in the river that reaches a certain point above sea level. Strictly speaking, achieving “Flood stage” in the Red River implies that it has overtopped the 18’ and is thus adversely impacting some entity either directly or indirectly. Elevation is defined from the river bed. This is important for the RRN because the river has had a trend of increased flooding in the last 100 years with almost 5 times as many occurrence in the most recent 50 years as in the first 50 years.

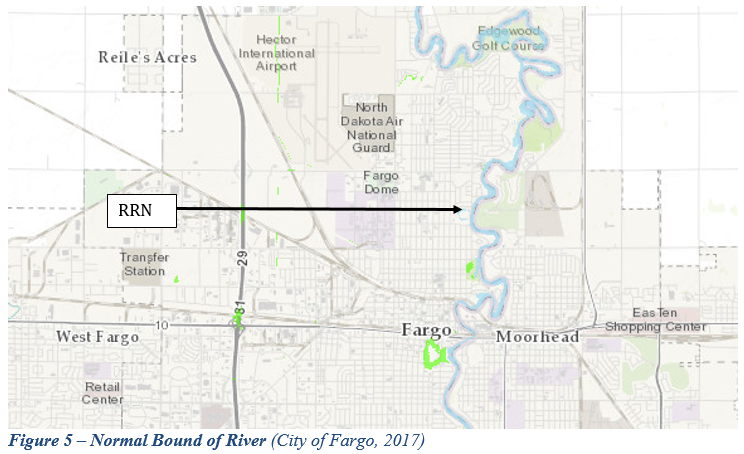

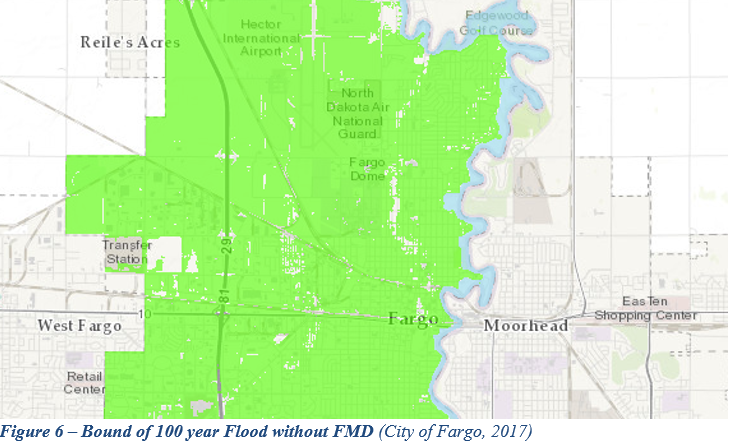

This frequency, along with the flat topography mentioned previously, has led to catastrophic flooding in areas north of the FM area during previous years, as well as emergency measures that were implemented in the FM area itself. This was particularly acute in 2009 when the city narrowly avoided inundation. The people in the valley are accustomed to dealing with flooding, but historically the ultimate solution has been disputed. This is particularly magnified because of the high degree of uncertainty that the valley experiences during flooding season. Flooding itself, which depends highly on snow melt in the basin and thus on weather patterns, is often very difficult to predict accurately. Figures 5 and 6 show the normal bound of the RRN and the 100 year flood level without the proposed FMD.

Environmental

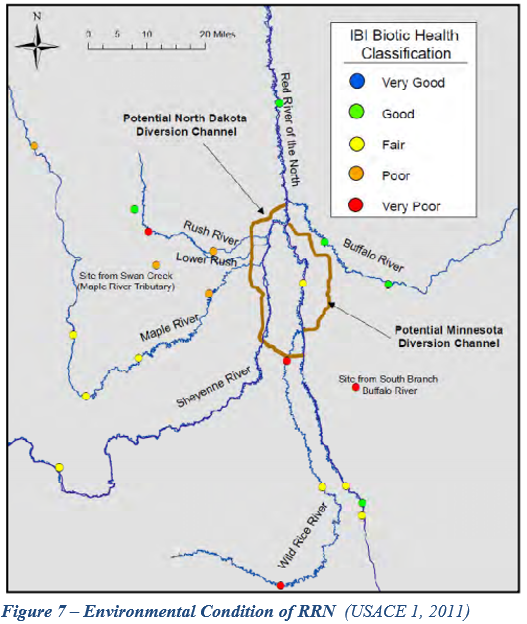

The RRN is often highly utilized by the communities as a hub for outdoor activities. Yet the current state of the adjacent riparian environment is degraded from pristine in both the RRN and it adjacent tributaries (USACE 1, 2011). This is primarily due to modifications that have already been made on the RRN and its tributaries to modify its flow in one way or another. The water quality is rated as being acceptable for most uses, and is suitable for the fish that inhabit it. The fish and wild life populations are reduced from their historic levels as would be expected for areas of development, but for certain species, efforts are currently underway to improve the situation (USACE 1, 2011).

Political

The FM area has a dichotomy of liberal and conservative politics. But, after the most recent flood event that occurred, which impacted all in the FM area, there was a unified sense from both political sides that something permanent needed to be done to solve the flooding issue. The consensus is partially drawn from the fact that the communities have often been drawn together during trying periods, and have narrowly succeeded installing temporary flood measures that protected the cities. Thus, in terms of the FM area there is a high degree of unity in terms of achieving the goal at hand. This unity is reflected also in all the decision makers that represent the area. Furthermore, the State of ND is very supportive of any efforts to improve the situation as well. The primary opposition is only from the MNDNR and the RWJPA.

Economic

The FM area is a multi-billion economic center (Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority, 2017) in North Dakota. It is also a large economic center for Western Minnesota as well. Currently the residents of the FM area pay a large amount of flood insurance due to their residence in an established US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) flood plain. This has added a large incentive to reduce premiums. In order to make the project happen, there is currently a large amount of Federal, State, and Local funding is available for the project, and the members of the community have been shown to be extremely willing to engage in talks that reduce their economic burden and foot a large portion of the bill though tax increases.

History of the Problem

Build-up Prior to Disputes

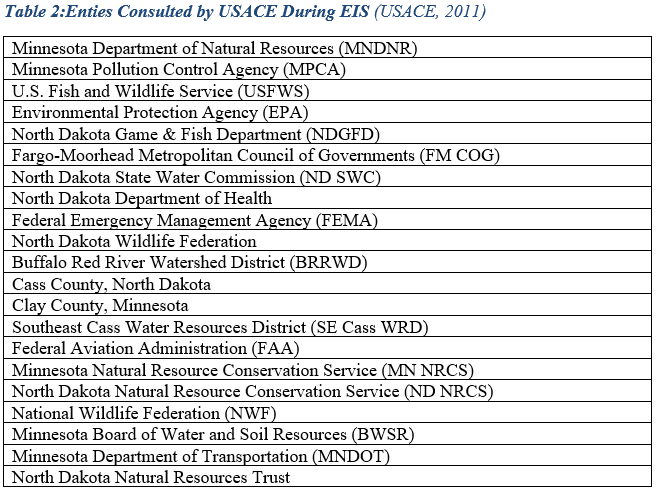

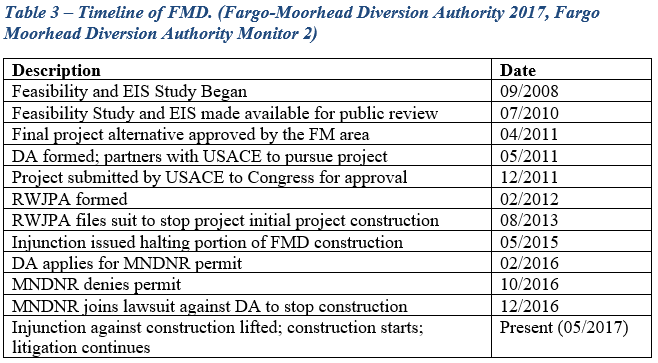

In 2008, a feasibility and environmental impact study (EIS) were begun by the USACE to assess alternatives for flood mitigation in the FM area, along with highlighting opportunities for environmental and recreational improvements that would work in tandem with existing flood control structures (Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 1, 2017). The economics of this problem were the primary motivation for flood mitigation and helped show the need for a long-term solution. The FM area saw that saving money would be on two fronts: elimination of emergency measures and reduction in flood insurance. For example, the FM area spent $70 M during their most recent flood emergency. In addition, even without spending on emergency measures, the area was estimated to be accruing US$195,000,000 in annual residual damages from flood insurance and related expenses that resulted from the FM area being within a flood plain. Thus, accounting for the cost of the diversion, after taking into account expenses, it was found that up to a 1.74 benefit/cost ratio could be created by the project (USACE 1, 2011). The EIS and feasibility study found that flood control was feasible in the FM area. Thus, the USACE began to work with state and local agencies to formulate flood control alternatives. The USACE worked with the parties listed in table 2 to understand the issues currently present on the RRN and to formulate a solution that met all goals highlighted by the FM area.

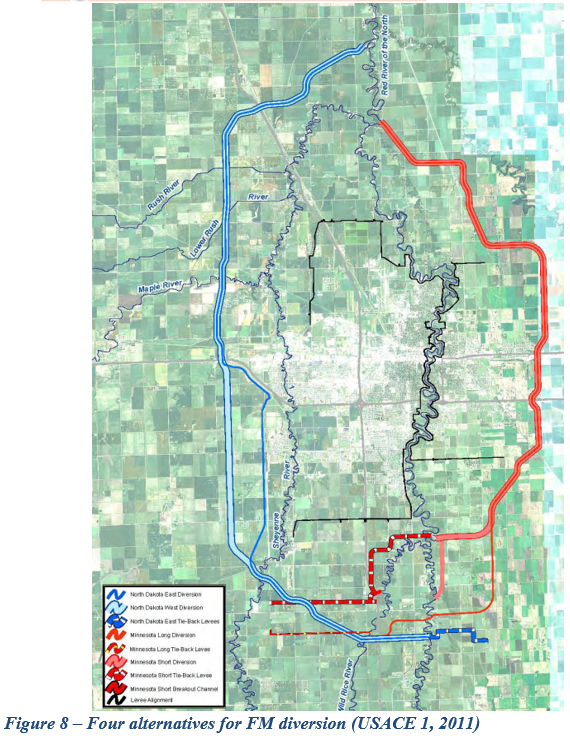

The EIS study and the feasibility study allowed the USACE to understand which alternatives would meet the desired objectives. Pairing the results of the studies, the USACE presented 3 possible solutions (not including the “do nothing” option) for flood protection in the FM area. They consisted of three separate routes that diverted part of the water in the river into a separate channel around the FM area to prevent it from passing directly between the cities. The USACE explored options that simply would have allowed the high portions of the channel flow that passed through the town to be confined with levees, but those options proved unable to meet the level of flood protection required by the cities (USACE 1, 2011). The three alternatives are noted in figure 8.

Since the river acts as the border between MN and ND, the diversion options were to primarily divert water through one state or the other. In the final proposition, 3 of the 4 solutions shown in figure 8 were proposed. Two solutions were proposed to go through ND, and one option was proposed to go through MN. After the MN state government expressed concern about the option going through MN, the MN option was dropped. By early 2011, the USACE completed their study and proposed a final solution to policy makers in the FM area (Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 3). The solution proposed used the ND East route (See figure 8), and was presented as maximizing all relevant benefits. According to the USACE, the selected alternative reduced the risk of flood damages in the FM to a reasonable factor of safety; it restored and improved the degraded RRN riparian ecosystem, and provided additional wetland habitat, along with recreational opportunities (USACE 1, 2011). Moreover, they stated that the solution provided the least impact on the Canadian side of the border to create a more viable international solution. They said further that it provided the least impact downstream overall, which minimized the effect on further development in the Northern Red River valley. The solution also sought to account for history by understanding that it was likely a flood event worse than any on record would happen at some point in the future. Thus, the FM area, having had quite a battle with 50 year floods was given a solution that was designed for 100 year floods. Environmental factors were not a key in driving the discussion of solutions because they were considered to be less of a priority than the flood protection and development (USACE 1, 2011). Water quality was not going to be affected in the long term, wetlands and habitats were going to be eliminated by construction, yet more were proposed as a part of the project (USACE 1, 2011). The USACE proposed the project in early 2011, after which it was approved by all leaders in the FM area (Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 3, 2017). Due to the history of flooding, there was a large amount of support that was offered at the local level. The policy makers who had met to approve the project from the USACE initially, formed themselves into the DA. Their goal was to act as a spearhead for the project, and unify local constituencies. Once the project was approved locally, the newly formed DA partnered with the USACE to gather resources to develop and finish the project. In late 2011, the USACE submitted its formal report to congress, beginning the process of obtaining federal funds and approval for the project (USACE 4, 2011). By May of 2014, the US congress authorized a portion of federal funding for the project. This was paired with local funding which by that time was substantial enough to cover the remainder of the project.

Key Disputes

There are certain issues that plagued the project. The inability to resolve these disputes led to litigation. Starting in 2012 and up to the present, as the FM diversion project was developed, the MNDNR and RWJPA began to highlight issues that they were unwilling to overlook.

RWJPA

The initial disputes in the project were brought out by the RWJPA beginning in 2012 (Fargo Moorhead Diversion Authority Monitor, 2012. As stated in table 2, the diversion plan was discussed with multiple parties as the USACE went through the planning process, determining what would be workable solutions. Furthermore, the USACE released its EIS and feasibility study to the public and to various agencies for comment twice during the planning process. The USACE stated that they integrated these comments into the final consideration of the alternatives (USACE 1, 2011). The alternatives, and the final plan that was agreed upon, were based on the findings of the EIS. However, parties in communities upstream, notably Richland and Wilkins counties, were omitted from the local authority comments on the study and were not considered substantial actors in the plan taking place. As a result, there was not an understanding of what would be acceptable execution for the FMD alternatives for either Richland or Wilkins county. In order to better voice their concerns, Richland and Wilkins County formed the RWJPA to represent the residents in the two respective counties (Larson, 2012). After failing in discussion, and to halt the project, the RWJPA filed an injunction with the MN state district court seeking to block the preparation construction from taking place (Von Korff , 2013).

MNDNR

The MNDNR brought out a set of disputes that were initially separate from the RWJPA. The MNDNR argued that the project did not properly account for public health, safety and welfare of citizens, and did not represent the minimal impact solution for the problem at hand (MNDNR , 2016). Furthermore, that there were significant environmental impacts that were not being accounted for in the selected FMD alternative. The MNDNR concern with public welfare centered around the requirement for a dam that had been integrated as a portion of the flood control for the project. It stated that the USACE had incorrectly portrayed the potential adverse affect that the dam that could have on people’s lives in the event of a failure (MNDNR, 2016). Furthermore, the MNDNR argued that the project advanced the interests of the FM area while violating the rights of upstream communities, both in terms of the allocation of stress due to risk of flooding, and due to shifting of the requirement for flood insurance from FM further upstream. Also, it postulated that this was done by inflating the perceived benefits of the project, and thus allowing the project to be billed as better than reality allowed (MNDNR, 2016). Finally, the MNDNR voiced the opinion that the FMD would not sufficiently give concern to environmental issues that would come about through the project. In their fact-finding process, they argued that USACE and DA mitigation plans for the environment in the context of the FMD were not sufficient, and that the overall plan proposed for the diversion did not include enough of a means that would allow for consistent monitoring of systems put into place to continually assess environmental impacts (MNDNR, 2016). As a part of the dispute, the MNDNR informed the DA that because a portion of the project was proposed to be constructed in Minnesota, that the DA would need to apply for permit to allow construction. The DA questioned this claim since the project was being built by the USACE which would imply that the project would bypass state regulations, since that due its responsibilities, the USACE has authority over the navigable water ways of the US (USACE 2). Yet, in the interest of eliminating issue of jurisdiction and to hasten the process, the DA applied for the permit in early 2016 (MNDNR, 2016). After reviewing the application, the MNDNR denied the application saying that that the FMD’s environmental and social impacts did comply with MN state law. According to documentation, (USACE 1, 2011), the USACE consulted consistently with the MNDNR to determine what sort of FMD would be acceptable to the agency in terms of its concerns. Yet, the denial of the permit application suggests there was not enough communication between the two agencies. The MNDNR filed a lawsuit in tandem with the RWJPA arguing that the FMD was a violation of MN state law since the DA did not have a permit. The DA subsequently argued that there was no need for one due to the involvement of the USACE.

Project Timeline

The Current State and Conflict

Ongoing and Past Efforts

Currently construction is proceeding, as is litigation. The original suit of irreparable harm being done by the project, and the violation of MN state law is still in question. However, the DA is actively attempting to resolve issues that stand in the way of construction, and to negotiate with parties that challenge the project (Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 4, 2017). In addition, both the USACE and DA are actively communicating with the MNDNR to determine what steps need to be taken to resolve MNDNR environmental and social concerns.

Why have issues surfaced?

Due to population and economic status, the DA consists of the most powerful sub-state political entities in ND and in western MN. Moreover, because of FM economic clout, both ND and MN are committed to trying to ensure the safety of the large amount taxable income that the FM area generates. In addition, the FM area is growing and many of the smaller towns are uneasy about the increasing footprint of the cities (Miller, 2012). The DA has been unsuccessful in gaining an understanding of what needs to be done to mitigate the issues of concern for the RWJPA and the MNDNR, which hence implies that the DA has been unable to communicate effectively with RWJPA. As the parties move forward, the cost and repercussions of continued litigation and absence of solution mount further. For example, the cost of litigation for the project is over $US3,500,000 (Fargo Moorhead Diversion Authority Monitor 1, 2017). Hence, the trust issues at hand should be considered. Through building trust and communication, the parties involved can begin to find common ground in the dispute so that the a unified front with the goal of providing flood protection and stability to the entire Red River valley can be found.

Recommendations for Problem Solving

The basic issue that needs to be dealt with in this case is trust and a common understanding of the mutual goals for all the involved parties. To build the understanding necessary to complete those fundamental objectives, practical steps need to be taken. A common theme in the case is that the leaders on various sides can be quoted that they are “working with the other parties to resolve the issues.” Most notably, there have been small conferences, private meetings, public meetings, requests for input on project details, and studies. All these have failed to bring consensus to the issues that are currently in litigation. A fundamental issue, is that there is lack of agreement on the facts, such as water modelling, net environmental impacts, quantification of flood levels, and socio-economic. Therefore the parties need to agree on a foundation that begins with some sort of joint fact finding process that either includes the USACE working closely with the disputing parties, or uses a jointly agreed upon third party that will render a mutually acceptable set of data. The disputing parties do not trust the core data and analysis, therefore, there needs to be better understanding of just how to quantify the impacts. A second issue is that there has been no evidence shown of a mutual gains approach being used. It appears that the groups are very fixated on the diversion itself, and have thus eliminated creative ways that the groups can meet the interests of both parties. A practical way to find new solutions would be to have a series of informal meetings involving leaders of the DA and RWJPA. The sole purpose could be to generate different alternatives that resolve the conflict, requiring benefits to be allocated to all parties involved. In structuring the discussion, since there has been an issue of implementation of feedback, it would be key to emphasize how the implementation of an alternative would be measured, and what the timeline would look like. It would be helpful to break the leaders into small groups so that discussions could be conducted without the worry of the opinions of constituents. Conducting all discussions with confidence agreement in place would further aid genuine expression. Conclusions and Summary

The FM diversion case presents many lessons than can be learned. First, the importance of communication is highlighted: that there is much more to a public project than simply coming up with a design. There must be active communication from those significantly affected. Also, there are opportunities to take multiple approaches that consider the needs of all involved. This can be done with a mutual gains approach, working through concepts like joint fact finding. The fact that all stakeholders in the valley need to recognize, is that if a solution is not found, and some sort of step is not taken to reduce the flooding risk at large, in the event of a flood, the entire valley will suffer, and not just one community. Because of the intertwined aspects of the region, if one area suffers, then then remainder will be impacted in one way or another. Thus, the longer the parties take, the more likely that this year they get hit by the “big one”.

Issues and Stakeholders

Stakeholder Goal Summary

NSPD: Ecosystems, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Community or organized citizens

Discussion

NSPD: Ecosystems, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Community or organized citizens

The DA desires a long-term solution to flooding, so that emergency measures will not have to be taken in the future. They would also like to protect and ensure future development around the FM area so that the growth of the region is not stymied (Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority, 2017). The USACE is concerned with ensuring development in the FM area, and protecting the development that is already present (USACE 3). The MNDNR wants to ensure that the environment and the welfare of the people is safeguarded in the spatial area of the project. They do not think that the project does this properly. Thus, they are working to stop the project in favor of trying to find an alternative (MNDNR). The RWJPA wants to protect the welfare of the people that it represents. The FMD threatens the welfare of the people by putting flood water in areas of both counties that have not had flooding before. The posit that this water and other upstream impacts will do irreparable harm to the people living in the counties, and thus oppose the project (Von Korff, 2013)

The DA, MNDNR, RWJPA, and USACE are attempting to resolve issues, that could delay construction, through an out of court solution. There are no other major stakeholders that are not being included in the discussions. Due to a lack of trust and mutual understanding by the parties involved in this project, problems have arisen that have caused an inability to find solutions that serve all parties involved. Therefore, an increase in trust would be applicable to allow the parties to build a consensus and to work towards solutions that emphasize mutual gains and a joint understanding of the project.

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreNo ASI articles have been added yet for this case

Key Questions

Transboundary Water Issues: How can mutual trust amongst riparians be nurtured? What actions erode that trust?

Case shows the results of extended negotiation that does not recognize needs of the other party

Tagged with: Red River Flood USACE

References

Bibliography

Brisbois, L. I. (2017). CASE 0:13-cv-02262-JRT-LIB. Retrieved from fmdam.org: http://fmdam.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/D436-Brisbois-Discovery-order-5-4-2017.pdf

City of Fargo. (2017). Flood Stages. Retrieved from http://gis.cityoffargo.com: http://gis.cityoffargo.com/FloodStages/

Fargo Moorhead Diversion Authority Monitor 1. (2017). Fargo Dam and FM Diversion Costs as of February 28, 2017. Retrieved from www.fmdam.org: http://fmdam.org/fargo-dam-and-fm-diversion-costs-as-of-february-28-2017/

Fargo Moorhead Diversion Authority Monitor. (2012). Richland Wilkin Joint Powers Authority commences Legal Challenge to expanded Fargo-Moorhead Flood Diversion Project. Retrieved from www.fmdam.org: http://fmdam.org/richland-wilkin-joint-powers-authority-commences-legal-challenge/

Fargo Moorhead Diversion Authority Monitor. (2017). Home. Retrieved from www.fmdam.org: http://fmdam.org/

Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 1. (2017). Project Area History. Retrieved from http://www.fmdiversion.com: http://www.fmdiversion.com/project-area-history/

Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 2. (2014). Diversion Coordination with Minnesota DNR Ongoing. Retrieved from www.fmdiversion.com: http://www.fmdiversion.com/diversion-coordination-with-minnesota-dnr-ongoing/

Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority. (2017). Why is it Needed? Retrieved from http://www.fmdiversion.com: http://www.fmdiversion.com/why-is-it-needed/

Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 3. (2017). About the Diversion Authority. Retrieved from www.fmdiversion.com: http://www.fmdiversion.com/who-is-the-diversion-authority/

Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 4. (2017). Court Refuses to Reinstate Dismissed Claims Against the Diversion Authority; Reinstates Corps as an Active Defendant . Retrieved from www.fmdiversion.com: http://www.fmdiversion.com/court-refuses-to-reinstate-dismissed-claims-against-the-diversion-authority-reinstates-corps-as-an-active-defendant/

Fargo-Moorhead Diversion Authority 5. (2017). Home. Retrieved from www.fmdiversion.com: http://www.fmdiversion.com/

Google. (2017). Maps. Retrieved from Google Maps: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Mass+Alliance-Portuguese+Speakers/@36.8741751,-107.1852374,4.25z/data=!4m5!3m4!1s0x89e370b482283743:0x91017253bcf265fb!8m2!3d42.3727699!4d-71.094753

Larson, M. (2012). Richland and Wilkin Counties Unanimously Form JPA. Retrieved from www.fmdam.org: http://fmdam.org/richland-and-wilkin-counties-unanimously-form-jpa/

Miller, P. (2012, August 16). Defending Richland-Wilkin Counties. Retrieved 2017, from http://www.wahpetondailynews.com/: http://www.wahpetondailynews.com/opinion/editorials/defending-richland-wilkin-counties/article_6007faf2-e7cb-11e1-9c76-001a4bcf887a.html

MNDNR . (2016, October 3). Fargo-Moorhead Dam Safety and Public Waters Work Permit Application 2016-0386 Findings of Fact. Retrieved from http://www.dnr.state.mn.us: http://files.dnr.state.mn.us/waters/surfacewater_section/damsafety/fargo_moorhead-findings_of_fact.pdf

MNDNR 1. (2017). Fargo-Moorhead Metropolitan Area Flood Risk Management Project - Environmental Review. Retrieved from www.dnr.state.mn.us: http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/input/environmentalreview/fm_flood_risk/index.html

NRCS. (2017). Red River Basin Initiative. Retrieved May 15, 2017, from www.nrcs.usda.gov: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/programs/initiatives/?cid=stelprdb1117397

Tran, T.-U. (2016). Feds formally commit to start F-M diversion. Retrieved from www.inforum.com: http://www.inforum.com/news/4071674-feds-formally-commit-start-f-m-diversion

USACE 1. (2011). Final Feasibility Report and Environmental Impact Statement: Fargo-Moorhead Metropolitan Area Flood Risk Management. St. Paul: USACE. Retrieved from http://www.fmdiversion.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Main_Report_with_Attachments.pdf

USACE 2. (n.d.). Legal Definition of “Traditional Navigable Waters”. Retrieved 2017, from http://www.usace.army.mil: http://www.usace.army.mil/Portals/2/docs/civilworks/regulatory/cwa_guide/app_d_traditional_navigable_waters.pdf

USACE. (2011, September 23). Fargo-Moorhead Metropolitan Area Flood Risk Management Feasibility Study Report and Environmental Impact Statement. Retrieved from International Water Institute: http://www.iwinst.org/feasibility/110923_FMM_CWRB.pdf

USACE 3. (2016). Corps awards its first contract for Fargo-Moorhead diversion project. Retrieved from www.fmdiversion.com: http://www.fmdiversion.com/corps-awards-its-first-contract-for-fargo-moorhead-diversion-project/

USACE 4. (2011). Proposed Report of the Chief of Engineers. Retrieved from www.iwinst.org: http://www.iwinst.org/feasibility/Proposed_Report_Chief_of_Engineers.pdf

USDA: Economic Research Service . (2017). U.S. Sugar Production . Retrieved from www.ers.usda.gov: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/sugar-sweeteners/background/

Von Korff, G. W. (2013). Appendix H - North Dakota Legislative Branch. Retrieved from www.legis.nd.gov: http://www.legis.nd.gov/files/committees/63-2013nma/appendices/wt090513appendixh.pdf

World Atlas. (2017). The Top Sugar Beet Producing Countries In The World. Retrieved from www.worldatlas.com: http://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-top-sugar-beet-producing-countries-in-the-world.html

| Area | 1,000 km² (386.1 mi²) + |

| Climate | Continental (Köppen D-type) + |

| Geolocation | 46° 53' 16.6571", -96° 44' 17.2851"Latitude: 46.8879603029 Longitude: -96.7381347623 + |

| Issue | Stakeholder Goal Summary + and Discussion + |

| Key Question | How can mutual trust amongst riparians be nurtured? What actions erode that trust? + |

| Land Use | urban + |

| NSPD | Ecosystems + and Governance + |

| Population | 220,000,000 million + |

| Stakeholder Type | Federated state/territorial/provincial government +, Local Government + and Community or organized citizens + |

| Topic Tag | Red River Flood USACE + |

| Water Use | Domestic/Urban Supply +, Fisheries - wild + and Recreation or Tourism + |

| Has subobjectThis property is a special property in this wiki. | Red River of the North - Fargo-Moorhead Diversion + |

There are no

There are no