Integrated Management and Diplomacy Development of the Chao Phraya River Basin

| Geolocation: | 13° 45' 9.8088", 100° 31' 29.6484" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 2525,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 157925157,925 km² 60,974.843 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Monsoon, Dry-summer |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, agricultural- confined livestock operations, industrial use, urban, urban- high density |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation, Industry - consumptive use, Industry - non-consumptive use |

Contents

[hide]- 1 Summary

- 2 Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

- 3 Issues and Stakeholders

- 4 Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

- 5 External Links

Summary

The Chao Phraya River Basin (“the basin”) is the largest river basin of the Kingdom of Thailand and plays a significant role in terms of agricultural, industrial and economic development. In recent years, there has been a series of extreme drought and flooding that increasingly challenge the management of the entire basin. For example, the major flood in 2011 has set a new precedent in terms of scale and scope of the issues at hand. As a consequence, one should wonder if and how the current assumptions and implications underlying the current practice should be reassessed. Considering the Water Diplomacy Framework, the management of the basin could be assessed and improved in a number of following ways.

- Recognize growing uncertainty of the water resources in the basin, particularly under the ongoing climate-change circumstance. This concern applies not only to the precipitation and runoff prediction, but also to the definition of zones of complexity of shared interests, particularly in the middle basin and the delta;

- Participate in the joint fact-finding process, engage in a value-creation process and commit to the consequent agreements; and

- Continually learn and adapt to emerging incidents and situations, and set priorities toward cumulative benefit not only for one specific party or group of interest, but rather for the entire basin.

As a consequence, the policy and politics of the Chao Phraya River Basin management should operate on a nonpartisan, impartial and fact-based platform. The management should also consider the dynamics and limited predictability of the resources, diverse interests of people and the communities, and the interdependence of economic, societal, policy and political dimensions of the commitments and consequences from prior and current decisions.

Structure of the first publication[1]

The discussion comprises nine sections. The case first discusses the importance of the basin and implications in natural/environmental, policy and political terms. A brief description of the basin history and stakeholders renders a discussion basis of the integrated management and challenges in two senses: a conventional view encompassing seasonal challenges such as drought and flood control and an emerging view with extreme conditions since 2011. Focusing on the latter circumstance, the depth of the discussion is extended to emerging challenges as a consequence of the increasing extremity likelihood. Resolutions in response consist of a a proposal of a Master Plan on Sustainable Water Resource Management and a complementary analysis in the sense of the Water Diplomacy Framework.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

The Chao Phraya River, together with the Mekong River, is the most important river in Thailand, as the entire river stretches across a significant amount of area: from the upper basin via its tributaries in the northern part of Thailand, to the middle basin where the confluence of Ping and Nan Rivers, the two major tributaries, is located, and flows southward to the delta into the Gulf of Thailand. The entire area is denoted as the Chao Phraya River Basin (See Exhibit 1).

Context of the Chao Phraya River Basin[2]

Evolution of the Basin Significance

The Chao Phraya River, together with the Mekong River, is the most important river in Thailand, as the entire river stretches across a significant amount of area: from the upper basin via its tributaries in the northern part of Thailand, to the middle basin where the confluence of Ping and Nan Rivers, the two major tributaries, is located, and flows southward to the delta into the Gulf of Thailand. The entire area is denoted as the Chao Phraya River Basin.

The Chao Phraya River Basin is rich in the history of Thailand, dating back to the Sukhothai (700 years ago), Ayutthaya (500 years ago) and Thonburi (250 years ago) Kingdoms. Cultural, social and political developments of Thailand over the years have transformed the basin, and the basin inherited significant endowments in terms of population settlements; the basin also preserved the traditional and cultural heritage that are still present in Thailand and the Thai culture today.

Nowadays, the basin is home to approximately 40% of the country’s population, with farmers as the majority in the upcountry and urban dwellers in Bangkok and other big cities in the basin such as Chiang Mai, Ayutthaya and Nonthaburi. With significant agricultural development since the middle of last century, water irrigation and related infrastructure developments such as dams and reservoirs have been constructed to increase the scale, scope and efficiency particularly to develop all-year agricultural activities. The rationale is: with preserved water supply by the dams, additional water-intensive agriculture can be developed in the dry season, rendering a positive impact in the sense of economic, trade and labor policies.

Together with the growing demand for electricity, driven by economic advances, large dams were constructed to serve both agricultural and hydropower generative ends. In particular, the Bhumibol dam (749 MW) on the Ping River and the Sirikit dam (500 MW) on the Nan River together control over one-fifth of the basin annual runoffs combined. Control of these dams therefore plays a major role in regulating water supply in the middle basin and the delta area.

In addition, it is also intended that the dams would assume additional functions, such as management of saline incursion, especially during the dry season when there is salt water intrusion from the Gulf of Thailand to the agricultural areas in the delta and middle basin; flood mitigation by limiting runoffs from the dams during the monsoons; and preservation of natural ecosystem in the upstream reservoirs and promotion of tourism.

Significance of the Chao Phraya River Basin

The Chao Phraya River Basin is the largest river basin of the Kingdom of Thailand. Since it has no transnational boundaries, the Government of Thailand assumes a primary authority of the basin management. From Thailand’s perspective, the basin not only represents a substantial geographical area inhabited by approximately 40% of the country’s population, it is arguably the most important river basin at least in five terms:

- Irrigation: the basin supplies water to the country’s largest agricultural systems, which represent the principal proportion of the nation’s entire workforces, and is naturally home to traditions and cultural heritages;

- Industrial use: the basin is domiciled to a host of emerging manufacturing factories ranging from automobile to electronic and chemical sectors. The industry represents a lion’s share of Thailand’s economic output with strong growth prospect, and implies a need to increase the amount of water supply to support the industries;

- Urban water supply: the basin provides the largest proportion of water supply in Bangkok, the capital city, and the Upper Ping Basin, including Chiang Mai, the second largest city. With a projected growing population density, increase in water demands is anticipated;

- Dams: implies the management of an interdependence of hydropower generative sources and flood control via water release management, primarily at the Bhumibol and Sirikit dams that control over one-fifth of the basin annual runoffs combined. Control of these dams therefore plays a major role in regulating water supply in the middle basin and the delta area;

- Environment and cultural heritages: the basin, particularly in the upstream areas, is Thailand’s primary natural habitat of wildlife in a large natural preservation region. It is also home to the roots of Thailand’s cultural development since over 700 years ago.

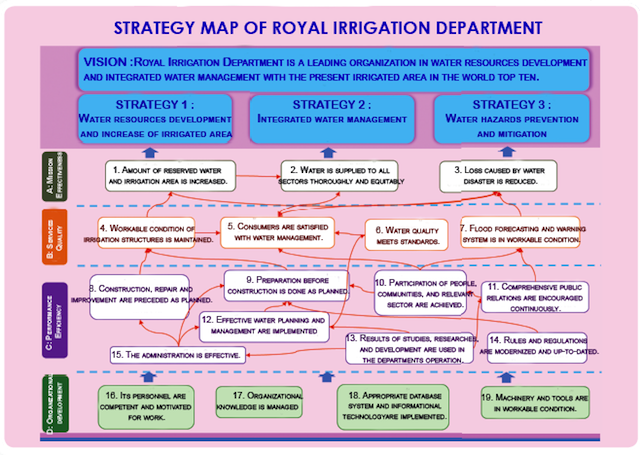

Traditionally, the planning and execution of water resources management in the basin and throughout the Kingdom of Thailand is the duty and responsibility of the Royal Irrigation Department (See Exhibit 2)[4]:

| Duty | Description |

|---|---|

| Water provisioning | Implementation of activities aimed at achieving, collecting, storing, controlling, distributing, draining or allocating water for agricultural, energy, household consumption or industrial purposes under irrigation laws, ditch and dike laws and other related laws |

| Damage prevention | Implementation of activities related to prevention of damages from water; safety of dams and appurtenant structures; safety of navigation in commanded areas and other related activities that may not be specified in annual plan |

| Agricultural land management | Implementation of land consolidation for agriculture under the Agricultural Land Consolidation Act |

| Miscellaneous | Implementation of other activities designated by laws or properly assigned by the Cabinet or Ministers |

However, since the turn of the century, the basin confronts a critical situation to preserve the sustainability of the basin, in terms of: matching the growing aggregate demand from the agricultural, industrial and urban uses with the limited supply; and managing the increasing predictability of seasonal precipitation, impacting particularly rain distribution and variation, in every single year and between consecutive years. This situation threatens not only the region, but also the entire country, because of the basin’s contribution relative to the nationwide level in terms of economic output from the agricultural and industrial to the service sectors; sources of employment, and implication of cultural heritages and communities; and urban area growth.

Challenges: Seasonality versus Emerging Extreme Conditions

Seasonality Challenges: Drought and Flooding Risks

The Chao Phraya Basin has experienced a higher frequency of extreme conditions (droughts and floods) within the last few decades. Presumable causes are deforestation, decreasing precipitation from climate change and increasing water abstraction especially in the upper basin[6]. Such occurrences cause a heightened stress in the basin, despite major engineering constructions that are designed primarily to mitigate droughts, e.g.:

- Storage of excessive rainfalls in the monsoon season by dams and reservoirs, such that there would be additional water supply for irrigation in the successive dry season. Water storage therefore enables agricultural activities for the entire year regardless of the dry-season severity;

- Improving scale, scope and efficiency of the canal and irrigation systems that stepwise increase the water service coverage, therefore decreasing the agricultural lands that solely depend on water supply from natural rainfalls. This effort increases the scale, scope and efficiency of the agricultural activities, provided that adequate water is available during the dry season by the dams and reservoirs located upstream.

On the other hand, the basin is vulnerable to great flooding risks, especially in the middle basin and the delta areas including Bangkok. With this concern, His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej initiates and patronizes Bangkok’s integrated flood management system[7] by heightening flood barriers in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area (responsible by BMA), improving river and drainage systems (by RID and PWD, respectively), building multipurpose dams (also by RID), and constructing temporary water storing areas[8] on the western and eastern coast of Chao Phraya estuary (by BMA and RID).

Emerging Extremity from 2011

Every year, one of the most important strategic decisions[9] focuses on the total amount of water that should be released by the dams during the 6-month dry season[10]. In general terms, the decisions are based on four criteria:

- Demand mainly from the agricultural planning, or the target volume;

- Rainfall forecast in the upstream and downstream areas of the basin;

- Carry-over water in the dam from the preceding monsoon season; and

- Regulated water level during the dry season.

In theory, the logic is to match the supplies in (2) and (3) with demands as specified in (1), by making sure the regulated levels of the dams do not deplete or overflow, specifically: The former concern of depletion raises the concern to ensure the dams will maintain adequate water supply, especially in an extremely dry year, until the end of the dry season, without breaching the minimum dam-level; whereas the latter concern of overflow prevention ensures that the dam will possess an adequate capacity to restore rainfall in the subsequent monsoon season, especially in an extremely rainy year, without breaching the maximum dam-levels.

However, this logic tends to be intractably complicated and as a result becomes a subject of mismanagement dispute from inadequate water supply (among RID, EGAT and PWA) or flooding (among RID, EGAT, PMA as well as BMA and MWA) that strongly affects the Bangkok Metropolitan Area. At the policy and political level, the Government of Thailand has become the focal point of dispute in the media, since it maintains an overall executive responsibility of the basin management.

In fact, potential causes of such practical challenges are varied and are not necessarily attributable to mismanagement of any one single party. The following are outstanding reasons of the management complexity on the basis of limited predictability with precision of:

- Water abstraction along the rivers and in the vast amount land in the basin further exacerbates the control mechanism;

- Rainfall forecasts, in the dry season and in the subsequent monsoon season. For example, a monsoon with high precipitation would require more water release from the dams and reservoirs in the preceding dry season, such that there would be adequate capacity to store excess rainfalls to effectively prevent flooding in the downstream.

The severe flooding in 2011[12] portrays an illustrative example. The incident started with an early monsoon season, where extreme rainfalls from March over the northern basin area reached 344% above mean[13] and caused significant runoffs from the upper basin to Bangkok. By the beginning of October, most major dams in the basin were already near or at the maximum capacity. As reported in the Nation daily newspaper from October 2, 2011[14]:Nine major dams are over 90 per cent "full", including Sirikit Dam in Uttaradit (99 per cent) and Bhumibol Dam in Tak (93 per cent).

As a result, engineers of the major dams were left with no choice but forced to increase the rates of discharges. From this moment, flooding in the basin was inevitable. Exhibit 3 shows a comparison of an example satellite photos before and after the flooding.

The incident affected 13.6 million people and 65 provinces and, as a result, damages amounted to 1.4 trillion Baht in total[15]. This extreme situation questions the long-standing challenges of the basin, particularly in terms of integrated management and natural limitation of the basin to handle emergency situation, as well as overlapping interests among institutions and the politics thereof. From an analysis of the timeline in this incident, one could infer the causes of the dispute from the following three examples:

- First, the potentially excessive use of groundwater may have undermined absorption and drainage capacity in case of flooding. The situation is exacerbated and complicated by inefficient canal and drainage systems in and around the cities. As cited by Bangkok Post on September 9, 2011[16]:Responding to growing public anxiety, the FROC director said it was very difficult to evaluate the flood situation because the water was moving underground through the city's sewers.

- Second, predictability of floods and joint fact-finding during the emergency hours were critical in the decision-making process but impossible to implement. As cited by Bangkok Post on November 11, 2011[17]:The Thai (Royal) Irrigation Department reported Bangkok flood waters could be drained in 11 days. Spokesman dismissed reports (that) the city could be hit by more waters from the North. Floodwater was described as being 1 km (0.62 mi) from Rama 2 Road and the situation "hard to predict”.

- Third, lack of a coherent implementation plan in the emergency phase led to resistance from people in the affected areas, in this case, those who dwelled outside the flood protection or “sandbag walls”. As cited by Bangkok Post on November 28, 2011 (7 days after the predicted “end of flood waters” from the previous paragraph)[18]:Residents in areas that remained flooded were growing more impatient. Sandbag walls were being sabotaged and sluice gate levels changed. Residents in some areas were said to be "poised to revolt”.

Aftermath: Proposal of a Master Plan on Sustainable Water Resource Management

In the aftermath of this severe flood in 2011, the Government of Thailand established the Strategic Committee for Water Resource Management and, as a response to the crisis, proposed Master Plan on Sustainable Water Resource Management[19], under the management of the National Economic and Social Development Board, a long-term strategic planning authority of the administration.

The overarching rationale of the Master Plan is to embrace the country’s development initiative under the guiding principle of His Majesty the King’s philosophy of Sufficiency Economy[20], while incorporating short-term action plans to (a) improve the capacity of flood prevention, emergency flood management and warning systems; (b) prevent and minimize losses and damages from the large-scale floods; and (c) build confidence and engage farmers and communities.

The action plans comprises 8 work streams involving over 20 different state organizations with a total budget of 300 billion Baht (i.e. approximately 2.6% of the national GDP in 2012). The lion’s share of the budget shall be allocated to:

- Restoration and efficiency improvement of physical constructions (e.g. water channels, dams and drainage, including land use zoning;

- Selection of water retention areas and recovery measures (in the same sense as mentioned as “temporary water-storing areas” in Sections Seasonality Challenges: Drought and Flooding Risks and Discussion: Ongoing Challenges After the Major Flooding in 2011);

- Restoration and conservation of forest and ecosystem particularly in the upper basin by focusing on reforestation and rehabilitation of the forest areas in the Chao Phraya River’s tributaries; and

- Establishment of an information warehouse, forecasting systems and disaster warning system.

As of 2013, it is still unclear how the government would finance this project; whether, when and to which extent this Master Plan will be implemented; and if the intended outcome could possibly be created at the targeted scale and scope, and sustained over the long haul.

Issues and Stakeholders

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Ecosystems, Governance, Assets, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Development/humanitarian interest, Environmental interest, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens

- Royal Irrigation Department (“RID”): a state department with responsibilities to provide all water supplies for irrigation throughout the year. Agriculture is the major concern. See also discussion of the organizational strategic responsibilities.

- Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (“EGAT”): a state enterprise that manages the majority of Thailand's electricity generation capacity. In this case, it operates dams to generate and stabilize the hydropower as a base load. However, owing to a broader and stronger energy mix in the recent decades, it becomes less dependent on the basin resources.

- Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (“BMA”): manages the urban city and maintains the integrity of water supply and flood protection in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area, together with the Metropolitan Waterworks Authority (“MWA”).

- Government of Thailand: the executive administration under the constitutional monarchy of the Kingdom of Thailand. It is responsible for the overall management of the water supply (i.e., manage, control and promote efficient use of water for agricultural, industrial, power generation and urban uses toward self-sufficiency). It established the Flood Relief Operation Center (“FROC”) during the major flooding in 2011.

- Provincial Waterworks Authority (“PWA”): a state department that provides water services in the Kingdom of Thailand, except for the Bangkok Metropolitan Area.

- Thailand Board of Investment (“BOI”): a governmental agency that promotes investment in Thailand and maintains contacts and relationship with foreign investors in Thailand.

- National Economic and Social Development Board (“NESDB”): a special governmental agency with responsibilities to formulate and develop national strategies that alleviate poverty and income distribution, enhance competitiveness, and promote social capital development and sustainable development.

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreDiscussion: Ongoing Challenges After the Major Flooding in 2011

As a result, the basin needs to cope with additional dimensions of the challenges:

- City management to mitigate risks of extreme events, eg, severe flooding, salinity incursion

- Balance of upstream and downstream resources, considering technical, societal & political aspects

- Industrial area protection to minimise risks from direct impact and manage investor’s confidence

- Trust in the management of the administration

Contributed by: Siripong (Pong) Treetasanatavorn (last edit: 11 May 2014)

Water Diplomacy Development in the Chao Phraya River Basin

Diplomacy Development Cornerstones:

- Define long-term engagement objectives: people

- Recognise the challenges: management of uncertainties

- Focus on consensus building & adaptive learning

- Strike a balance between preserving natural resources and managing the short-term practicality

Contributed by: Siripong (Pong) Treetasanatavorn (last edit: 11 May 2014)

External Links

- Chao Phraya River Basin (Thailand) — Water resources and socio-economic situation in the Chao Phraya basin

- ^ Published on May 11, 2014. The author would like to acknowledge valuable comments from Joyce Cheung and Itamar Shahar, also to Professor Lawrence Susskind and the entire Water Diplomacy class discussion on May 1, 2014. See further details about MIT Water Diplomacy at http://dusp.mit.edu/epp/project/water-diplomacy and Class 11.382 WATER DIPLOMACY: THE SCIENCE, POLICY AND POLITICS OF MANAGING SHARED RESOURCES at http://dusp.mit.edu/subject/spring-2014-11382-0

- ^ Contents in this section rely primarily on public information at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chao_Phraya_River http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhumibol_Dam http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sirikit_Dam http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_Thailand http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Thailand

- ^ Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tributaries_of_the_Chao_Phraya_River

- ^ See http://www.rid.go.th/ and also http://www.bangkokpost.com/business/13065_info_royal-irrigation-department.html

- ^ Source: http://www.rid.go.th/

- ^ Francois Molle, et al, “Dry-season water allocation in the Chao Phraya basin: What is at stake and how to gain in efficiency and equity”, Proceedings of the International Conference The Chao Phraya Delta, 2000.

- ^ Siripong Hungspreug, et al, “Flood management in Chao Phraya River Basin”, Proceedings of the International Conference: The Chao Phraya Delta, 2000.

- ^ See Water Detention Project or "Kaem Ling" (Monkey Cheeks in Thai) at http://www.chaipat.or.th/chaipat_old/n_stage/activities_e/ling_e/ling2_e.html

- ^ See Section 4.5 on page 20 from Francois Molle, et al, “Dry-season water allocation in the Chao Phraya basin: What is at stake and how to gain in efficiency and equity”, Proceedings of the International Conference The Chao Phraya Delta, 2000.

- ^ Thailand’s dry season runs from January to June, with the monsoon rainy season from July/August to November/December.

- ^ Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2011_Thailand_floods

- ^ Primarily from July 2011 to January 2012. See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2011_Thailand_floods

- ^ Bangkok Pundit, "The Thai floods, rain, and water going into the dams – Part 2", Asian Correspondent, November 2011: Source: Thai Meteorological Department Monthly Current Report Rainfall and Accumulative Rainfall March 2011.

- ^ "Major dams over capacity" The Nation, October 2011.

- ^ World Bank “The World Bank Supports Thailand's Post-Floods Recovery Effort” December 2011: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2011/12/13/world-bank-supports-thailands-post-floods-recovery-effort

- ^ “Froc admits it really doesn't know" Bangkok Post, September 2011.

- ^ “Capital could be dry in 11 days”, Bangkok Post, November 2011. Also at Wikipedia entry: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2011_Thailand_floods#Timeline_of_protecting_downtown_Bangkok

- ^ “Residents poised to revolt" Bangkok Post. November 2011.

- ^ “Master Plan on Water Resources Management”, Office of National Economic and Social Development Board, Thailand, January 2012.

- ^ “Philosophy of Sufficiency Economy”, the Chaipattana Foundation, accessible at: http://www.chaipat.or.th/chaipat_english/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4103&Itemid=293

| Area | 157,925 km² (60,974.843 mi²) + |

| Climate | Monsoon + and Dry-summer + |

| Geolocation | 13° 45' 9.8088", 100° 31' 29.6484"Latitude: 13.7527246644 Longitude: 100.524902344 + |

| Land Use | agricultural- cropland and pasture +, agricultural- confined livestock operations +, industrial use +, urban + and urban- high density + |

| NSPD | Water Quantity +, Water Quality +, Ecosystems +, Governance +, Assets + and Values and Norms + |

| Population | 25,000,000 million + |

| Stakeholder Type | Federated state/territorial/provincial government +, Local Government +, Development/humanitarian interest +, Environmental interest +, Industry/Corporate Interest + and Community or organized citizens + |

| Water Use | Agriculture or Irrigation +, Domestic/Urban Supply +, Hydropower Generation +, Industry - consumptive use + and Industry - non-consumptive use + |

This is the

This is the