Water Competition & Cooperation in the Las Vegas Valley

| Geolocation: | 36° 9' 49.284", -115° 11' 25.4328" |

|---|---|

| Total Watershed Population: | 30 million |

| Total Watershed Area: | 637000 km2245,945.7 mi² |

| Climate Descriptors: | Arid/desert (Köppen B-type) |

| Predominant Land Use Descriptors: | urban |

| Important Uses of Water: | Domestic/Urban Supply, Other Ecological Services, Recreation or Tourism |

| Water Features: | Colorado River |

| Riparians: | Nevada (U.S.), Arizona (U.S.), California (U.S.), Colorado (U.S.), New Mexico (U.S.), Utah (U.S.), Wyoming (U.S.), Mexico |

| Agreements: | Colorado River Compact, 2007 Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations, 1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty, Minute 319 |

Contents

[hide]Summary

The Las Vegas Valley, which includes the city of Las Vegas and the surrounding municipalities, is located in the Mojave Desert in Southern Nevada. Like most desert cities, Las Vegas exists because of water; the artesian springs of the Las Vegas Valley provided an ample water supply for Native Americans, ranchers and later a small railroad city. However, population growth increased demands far beyond local supplies. The area now depends on the Colorado River for the majority of its water supply. Natural scarcity, population growth and climate variability all contribute to the Valley’s water management challenges. This analysis addresses the following questions: 1) How can cooperation lead to better water demand management? 2) What conditions enable effective cooperation? The case demonstrates that a well-structured cooperative agency can prompt joint action by decreasing competition over water supplies. The Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA), a regional water utility made up of five water suppliers, was formed out of the water crisis that stuck the Las Vegas Valley in the late 1980s. Although the scarcity was key enabling condition for the creation of the SNWA, the transition would not have been as successful without the strong leadership present. Since its formation, the SNWA has fostered cooperation among the five water suppliers and contributed to substantial per capita demand reductions. However, as population growth continues and climate change exacerbates natural variability, the SNWA and its members will need to adapt to continue providing reliable water supply.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

The Las Vegas Valley is located in the Mojave Desert in Southern Nevada and receives about 10 cm (4 inches) of rainfall a year. Area municipalities rely on both groundwater and the Colorado River for water supply. Fast growing urban areas and a booming tourism industry have stressed water supplies. Natural climate variability with periodic droughts has further challenged water providers; projected climate changes will exacerbate these challenges.

Demographics

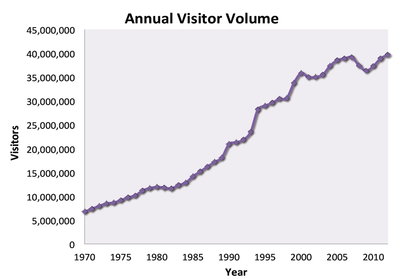

American settlement of Las Vegas began in 1855 when a group of Mormons built a settlement based around irrigated agriculture [1]. Soon after the Mormons abandoned the valley but ranching and irrigated agriculture continued. The town of Las Vegas was formed in 1905 as a railroad way station [2]. At the beginning of the 19th century, Las Vegas was a typical small western town. It grew rapidly in the 1920’s and 30’s, fueled by federal spending and an influx of workers for the Hoover Dam; government spending again fueled growth in the 1950’s as atomic testing and military training was conducted outside Las Vegas [3]. The rapid growth continued into the early 2000’s with Las Vegas being the fastest growing city, in the fastest growing state since World War II as seen in Figure 1 [4]. In addition to rapid population growth, Las Vegas has been a significant tourist destination since the 1930’s. Gambling was legalized in the 1931 and by 1935 Las Vegas was already established as a marriage destination due to California’s three day waiting period for a marriage license; Hoover Dam attracted new visitors and tourism further expanded in 1941 with the start of the resort industry [5]. Tourism continued to grow and Las Vegas saw a huge boom in tourism with annual visitors steadily increasing from 1970 until the mid-1990’s as seen in Figure 2 [6].

Governance

Las Vegas Land and Water Company

The Las Vegas Land and Water Company, which was owned by the Union Pacific Railroad, was the first water utility to serve the Las Vegas Valley. In 1931 the Land and Water Company was granted a 50 year franchise to provide water to the city of Las Vegas [3]. A 1945 study by the USGS showed that groundwater withdrawals were unsustainable and then, the city commissioned a survey to study the cost of bringing water from Lake Mead. The Land and Water Company, unwilling to invest in a pipeline from Lake Mead, decided in 1949 to sell the water system; the sale to the Las Vegas Valley Water District was finalized in 1954 [3].

Las Vegas Valley Water District

The Las Vegas Valley Water District (LVVWD), a public water agency, was authorized in 1947 as the town of Las Vegas was facing its first major water crisis [7]. The LVVWD was created in order to begin to use some of the state’s allocation of Colorado River water and to reduce groundwater usage. In 1952, the district signed an agreement with Basic Magnesium, Inc. to obtain a portion of the company’s water withdrawal from Lake Mead [3]. Throughout the 1950’s the LVVWD bought up small water systems serving the city to consolidate the water service operations [3]. The district’s responsibilities increased in the early 1970’s as it took control of the newly completed Southern Nevada Water Project and was tasked with developing a pollution abatement plan for the Las Vegas Wash [3]. The issue of pollution abatement also sparked the first plans for a regional water agency. Pollution in the Las Vegas Wash came from multiple municipalities, not all served by the LVVWD. Creation of a regional water utility was debated in the early 1970’s but no new agency was created at that time[3].

Southern Nevada Water Authority

The Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) is made up of the five water suppliers and two wastewater purveyors of the region including Boulder City, Henderson, Las Vegas and North Las Vegas, LVVWD, Clark County Water Reclamation District and Big Bend Water District [8]. In order to regionally manage water, the five suppliers combined their water rights and got rid of the system of priority rights [9]. In the authority all member agencies have equal power regardless of size and each of the water suppliers has veto power over decisions affecting the group [9]. Each utility runs its own operations but infrastructure, conservation and planning are implemented by the SNWA regionally [1]. Each municipality and county covered by the SNWA is also required to follow the agreed upon conservation standards. The approximate service area of the SNWA can be seen in Figure 3.

Law of the River

The partitioning, use and management of the Colorado River waters are governed by a collection of federal and state statutes, interstate compacts, international treaties, court decisions and contracts with the federal government known as the “Law of the River” [10]. The “Law of the River” dates back to 1922 when the Colorado River Compact was signed; in the years since the “Law of the River” has evolved with new agreements and court ruling being incorporated and parties shifting. The Colorado River Commission of Nevada was initially the party acting on behalf of the state of Nevada in all Colorado River agreements. However, in 1995 the responsibility shifted to the SNWA as the SNWA had become the major water delivery agency in the state [11]. The Colorado River Compact (Link to agreement article) allocates 300,000 acre-feet per year to Nevada. A few of the many other elements of the “Law of the River” are the Boulder Canon Project Act of 1928, the Mexican Water Treaty of 1944 and the Arizona v. California U.S. Supreme Court Decision of 1964 [12].

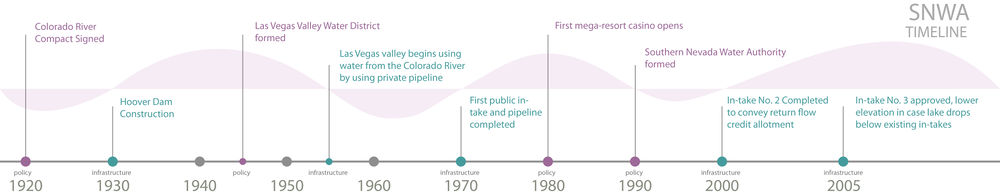

One of the most recent additions to the Law of the River is the 2007 Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations which provides temporary guidance on shortage management in the Colorado River Basin. Among other provisions, the Interim guidelines outline requirements for the creation and delivery of Intentionally Created Surplus (ICS) [13]. This provision allows states to earn additional Colorado River water credits through four mechanisms: (1) Extraordinary Conservation ICS, (2) Tributary Conservation ICS, (3) System Efficiency ICS and (4) Imported ICS. ICS is an innovative and flexible provision which encourages states to pursue projects increasing the efficiency of water systems. SNWA currently has several projects that make use of the ICS including the Virgin/Muddy Rivers Tributary Conservation and the Coyote Spring Valley Groundwater Imported ICS. However, the current ICS rules restrict projects to within the state earning the credit. This presents a challenge particularly for Nevada because, unlike other Lower Basin states, it has little agricultural use of mainstream water and no in state access to sea water for desalination [13]. Another recent addition is the 2012 Minute 319, an agreement with Mexico covering low and high reservoir level flow distribution, salinity and water for the environment. The temporary agreement requires Mexico to share the burden of flow restrictions during shortages but allows Mexico to share in surpluses and to store water in Lake Mead in order to better prepare for flow variability [14]. Figure 4 shows a timeline of implementation of major infrastructure works and policies affecting the Las Vegas Valley.

Water Supply & Demand

Groundwater

Groundwater was the historic water supply of the Las Vegas Valley. The local groundwater system is a two layer aquifer system consisting of a near surface aquifer and a deeper artesian aquifer. Recharge in the near surface layer is predominately from over irrigation and urban runoff while higher precipitation (around 50 cm or 20 inches per year) in the Mountain ranges surrounding the valley recharges the deep aquifer [10]. Historically, artesian springs could be found throughout the valley and were used by the Native American population for centuries [10] . Groundwater remained the primary source of water for the Valley until the early 1970’s. However, as the city grew groundwater usage quickly surpassed sustainable yield. Some areas of the Valley saw as much as a 45 m (150 ft) drop in groundwater levels from 1945 to 1995 [10], and in 1962 the Las Vegas springs first stopped flowing to the surface [7]. Today groundwater is still an important water source for the area and SNWA manages a mix of local and regional groundwater systems to supplement the Colorado River supply [8].

Surface Water

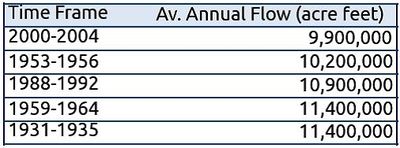

The Hoover Dam and Lake Mead Reservoir were completed in 1936 to provide storage and water supply for California, Arizona and Nevada. At the time Las Vegas still had sufficient groundwater to cover its demands and its use of the Colorado River water did not begin until two decades later. In 1955, the Las Vegas Valley Water District signed an agreement with Basic Magnesium, Inc., a private company, to use their existing pump station and pipeline [3]. In the early 1960’s the LVVWD began designing the Southern Nevada Water System which consisted of an in-take structure at Lake Mead, treatment works and distribution system; the first stage of the project, in-take No. 1, was complete in 1971. The second stage of the project, in-take No. 2, was completed in 1982 increasing capacity to 400 million gallons per day (MGD) [7]. In the early 2000’s drought conditions, as seen in Figure 5, threatened in-take No. 1 which would be out of service if Lake Mead levels dropped below 1050 feet. In 2005, the Southern Nevada Water Authority board authorized the construction of a third and lower in-take structure which is scheduled for completion in 2014 [15].

Recycled Water

Several wastewater treatment plants in the valley currently provide treated wastewater for reuse: the Boulder City plant, the Water Pollution Control Facility, the Bonanza Mojave Water Resource Center and Northwest Water Resource Center [8]. A portion of the treated effluent is used by the sand and gravel industry, golf courses, schools and parks. The remaining effluent is returned to the Colorado River; this earns return flow credits, allowing additional in-take from Lake Mead.

Conservation and Demand Management

The Las Vegas Valley has made numerous attempts at increasing water conservation in response to water shortages. In the 1940’s summer water shortages led to low pressure in the water mains and customers at higher elevations, including the second floor of a hospital, had no water service. The Las Vegas Land and Water Company instituted landscape water restrictions banning watering from 9 am to 6 pm [3]. There was a state law against water meters in town’s larger than 4,500 residents; in an effort to curb waste, the Las Vegas Land and Water Company attempted to repeal the law in the early 1950’s, but the legislature voted against it [3]. In 1955, the Las Vegas Valley Water District got an exemption from the metering ban and began to distribute water meters; in 1958, when 90% of customers had received meters volume based pricing replaced the previous flat rate [3].

Since its formation in 1991, the SNWA has used a combination of regulation, water pricing, incentives and education to promote water conservation. Regulatory measures include timing restrictions on landscape watering, ban of turf installation in new residential front yards, and golf course watering limits [8]. The SNWA has an increasing block price structure for water charges to discourage water waste. The utility also offers incentives for conservation measures including the following: tuft removal, efficient irrigation equipment, pool covers, water smart car washes, and Water Efficient Technologies [8]. Educational efforts include demonstration gardens, a conservation hotline and training for teachers [8].

Despite initial successes, critics argue that there is substantial room for further reductions. While outdoor conservation measures such as turf removal incentives have reduced demands, outdoor water use in Las Vegas is still higher than in other arid and semi-arid cities. Due to high outdoor water use the majority of conservation efforts in Las Vegas have focused on landscape use; Las Vegas has only achieved small gains in indoor conservation. The SNWA provides free retrofit kits (including leak detection and faucet aerators) to single family homes built before 1989 but no assistance or incentives for newer homes [16]. Multi-family homes are eligible for rebates through SNWA’s Water Efficient Technologies program but between 2002 and 2007 only 30 were claimed [16]. One reason for slow action on indoor conservation may be that SNWA earns return flow credits for treated wastewater returned to the Colorado and indoor use reductions would reduce this flow. However, benefits of indoor conservation would likely outweigh costs; the utility would reduce energy and chemical costs associated with water transport and treatment. Additionally, as the population grows, indoor conservation can allow more people to be served with the same amount of water while still generating return flows [16].

Issues and Stakeholders

Urban allocation and demand management

NSPD: Water Quantity, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Local Government

The four municipalities, Las Vegas, North Las Vegas, Henderson and Boulder City, along with Nellis Air Force Base and Clark County, are connected through their shared water supply. They collectively use the majority of Nevada’s Colorado River allocation and share an interconnected aquifer system. In order to regionally manage water, the five suppliers combined their water rights and got rid of the system of priority rights [17]. While each utility runs its own operations, infrastructure, conservation and planning were implemented by the SNWA regionally and each municipality and county covered by the SNWA is also required to follow the agreed upon conservation standards [18]. They have so far made substantial progress in controlling demands through cooperation having reduced per capita demands from 350 gallons per day in 1990 to 250 gallons per day in 2008 [19]. With some of the easiest conservation measures already taken, tougher changes may be required to meet future conservation goals.

Stakeholders

- SNWA and associated utilities and municipalities

- Associated utilities

- Big Bend Water District

- Clark County Water Reclamation

- Las Vegas Valley Water District

- Associated municipalities

- City of Las Vegas

- City of North Las Vegas

- City of Henderson

- City of Boulder City

- Nellis Air Force Base

- Clark County

Managing shortages in the Colorado River

NSPD: Water Quantity, Ecosystems, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Sovereign state/national/federal government, Local Government, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens

The Colorado River Compact allocated flow based on 22 year record of river flows which suggested that a flow of 16,500,000 was a conservative estimate; however, the natural average annual flow in the Colorado was just 15,000,000 ac-feet for hundred years from 1906 to 2006 [20]; [21]. Since the compact was written USBR flow estimates show that during several periods, average annual flows did not reach the allocated flow.

In response to the Colorado River Basin drought in the early 2000s, the seven basin states developed a proposal outlining shortage operations, the Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations, which was later adopted by the Secretary of the Interior [22]. The interim guidelines are set to expire in 2026 and, given the historical record and the regional climate projections, shortages will likely increase. Minute 319, a 2012 interim agreement between the United States and Mexico, states “both countries have recognized the value of an interim period of cooperation to proactively manage the Colorado River in light of historical and potential future increased variability due to climate change” [14]. The agreement outlines new guidelines for the distribution of flows during surplus and shortage conditions and outlines provisions for increased water for the environment in Mexico. The 2007 Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations and Minute 319 are both a step towards adapting the management of the Colorado River. However, both measures are temporary and the stakeholders within the states will likely need to renegotiate shortage rules in the future. Although the seven states and Mexico cooperated to develop the Interim Guidelines and Minute 319, they disagree in their interpretations of the various elements of the Law of the River including on how to determine deficit conditions and the legality of selling water across basin lines [23]. In addition to future climate and demand patterns, the resolution of these legal disagreements will affect the water availability in each of the basin states.

Stakeholders

- Lower basin states

- Arizona

- California

- Nevada

- Upper Basin States

- Colorado

- New Mexico

- Utah

- Wyoming

- Mexico

- SNWA and associated utilities and municipalities

- Water users within the other basin states

Urban purchase of rural groundwater rights

NSPD: Water Quantity, Governance, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Community or organized citizens

Despite conservation efforts and improved allocation schemes, local water resources and the Colorado River allocation are not sufficient to guarantee water supplies for urban and suburban Sothern Nevada. Therefore SNWA’s long-term plans also include: formulating a water resources plan that utilizes all available supplies including applying for use of un-appropriated groundwater located in other areas of Nevada [24]. The problem of water resource availability has been defined by the regional water utilities and their constituents and the SNWA has been successful in dealing with the problem as defined. The SNWA has been effective at coordinating water management within the five municipalities and Clark County; however, the impacts of its plans extend beyond the urban areas of Southern Nevada to rural residents and desert ecosystems. The SNWA filled 147 permits for groundwater application in 1989 in 30 different basins [25]. The “water grab”, as it was known in the rural counties, instigated an instant backlash [26]. Due to environmental concerns and existing appropriations the SNWA withdrew, transferred or declined to pursue 49 applications, limiting their requests to 21 different basins [27]. In addition to existing groundwater rights, there are concerns over how withdrawals may impact spring discharges and therefore surface water rights [28]. In 2003, SNWA developed an agreement with Lincoln County to resolve outstanding concerns over groundwater applications within the county [29].

Stakeholders

- SNWA and associated utilities and municipalities

- Rural municipalities

- Rural water rights holders

Groundwater withdrawals and ecosystem impacts

NSPD: Water Quantity, Ecosystems, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens

Despite the withdrawal of some of SNWA’s most controversial groundwater applications, environmental critiques remain. Deacon and colleagues [30], caution that the groundwater withdrawals planned by the SNWA present an underappreciated threat to the spring ecosystems and the species which depend on them. Twenty of those impacted species are listed under the federal Endangered Species Protection Act [31]. The SNWA as well as several independent researchers developed groundwater models to determine the probable future effects of groundwater development. All of the independent models showed significant declines in the effective basins except for the SNWA model which assumed higher levels of recharge due to precipitation [32]. In addition to varying assumptions on model parameters, there is disagreement on the proper method of calculating perennial yield. The Nevada Division of Water Resources defines perennial yield as “the amount of water from a ground-water aquifer that can be economically withdrawn for an indefinite period of time… and does not exceed the natural recharge” [33]. This definition allows the reductions in spring flows and decreases groundwater elevation that can cause detrimental impacts to plant and animal species [34]. Discrepancies in perennial yield definitions and modeling assumptions have not yet been resolved.

Stakeholders

- SNWA and associated utilities and municipalities

- Environmental groups

- Groundwater dependent species

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sections are protected, so that each person who creates a section retains authorship and control of their own content. You may add your own ASI contribution from the case study edit tab.

Learn more[[Formation of the SNWA: Cooperation in Demand Management]]

The formation of the Southern Nevada Water Authority stems from the stakeholders recognition of their interdependence. This case demonstrates that stakeholders need for cooperation, and therefore their willingness to cooperate, increases in proportion to the stresses on the system. It also demonstrates that good leadership was instrumental to the success of the Authority in controlling water demands and acquiring water supplies.[[Formation of the SNWA: Cooperation in Demand Management|(read the full article... )]]

Contributed by: Margaret Garcia (last edit: 20 May 2013)

Key Questions

In the Las Vegas Valley, municipalities competing for a limited water supply led to great inefficiencies. The formation of a cooperative water management utility created incentives for conservation and led to decreased water demands. Serious near-term shortages sparked interest in cooperation but good leadership was critical in navigating the transition.

External Links

- Las Vegas: Landsat Annual Timelapse 1984-2012 — Timelapse of Las Vegas area urban growth.

- Las Vegas Valley Water District — Website for the Las Vegas Valley Water District

- Southern Nevada Water Authority — Website for the Southern Nevada Water Authority

- US Bureau of Reclamation: Law of the River — USBR website outlining the numerous compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, contracts, and regulatory guidelines collectively known as the "Law of the River."

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Harrison, C. (2009). Water use and natural limits in the Las Vegas Valley: A history of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. University of Nevada, Las Vegas

- ^ Douglass, W. a., & Raento, P. (2004). The Tradition of Invention: Conceiving Las Vegas. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(1), 7–23. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2003.05.001

- ^ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Jones, F. L., & Cahlan, J. F. (1975). Water: a history of Las Vegas. Las Vegas Valley Water District

- ^ Douglass, W. a., & Raento, P. (2004). The Tradition of Invention: Conceiving Las Vegas. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(1), 7–23. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2003.05.001

- ^ Jones, F. L., & Cahlan, J. F. (1975). Water: a history of Las Vegas. Las Vegas Valley Water District

- ^ Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority (2013). Historical Las Vegas Visitor Statistics: 1970 to 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.lvcva.com/includes/content/images/media/docs/Historical-1970-to-2012.pdf

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Las Vegas Valley Water District [LVVWD]. (2013). Timeline of Las Vegas Valley Water District History. Retrieved from: http://www.lvvwd.com/about/press_history_timeline.html

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Mulroy, P. (2008). Beyond The Divisions: A Compact That Unites. Journal of Land, Resources, and Environmental Law, (1), 105–117

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Morris, R., Devitt, D. A., Crites, Z. A. M., Borden, G., & Allen, L. N. (1997). Urbanization and Water Conservation in Las Vegas Valley, Nevada. Journal of Water Resources Planning & Management, (123), 189–195

- ^ Ott Verburg, K. (2010). The Colorado River Documents 2008. United States. Bureau of Reclamation. Lower Colorado Region, United States. Bureau of Reclamation. Upper Colorado Region. Government Printing Office

- ^ USBR (2011a). USBR (2011b). Law of the River. Retrieved from: http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/lawofrvr.html

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Grant, D. L. (2008). Collaborative Solutions to Colorado River Water Shortages: The Basin States’ Proposal and Beyond. Nevada Law Journal, 8, 964–993

- ^ 14.0 14.1 International Boundary and Water Commission (2012, November). Minute 319: Interim Interational Cooperation Measures in the Colorado River Basin Through 2017 and Extension of Minute 318 Cooperative Measures to Address the Continued Effects of the April 2010 Earthquake in the Mexicali Valley, Baja California. Retrieved from: http://www.ibwc.gov/Files/Minutes/Minute_319.pdf

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2013) Regional Water System. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/about/regional.html

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Cooley, H., Hutchins-Cabibi, T., Chohen, M., Glieck, P. H. & Heberger, M. (2007). Hidden Oasis: Water Conservation and Efficiency in Las Vegas. Pacific Institute & Water Resource Advocates

- ^ Mulroy, P. (2008). Beyond The Divisions: A Compact That Unites. Journal of Land, Resources, and Environmental Law, (1), 105–117

- ^ Harrison, C. (2009). Water use and natural limits in the Las Vegas Valley: A history of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. University of Nevada, Las Vegas

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ Morris, R., Devitt, D. A., Crites, Z. A. M., Borden, G., & Allen, L. N. (1997). Urbanization and Water Conservation in Las Vegas Valley, Nevada. Journal of Water Resources Planning & Management, (123), 189–195

- ^ Grant, D. L. (2008). Collaborative Solutions to Colorado River Water Shortages: The Basin States’ Proposal and Beyond. Nevada Law Journal, 8, 964–993

- ^ Grant, D. L. (2008). Collaborative Solutions to Colorado River Water Shortages: The Basin States’ Proposal and Beyond. Nevada Law Journal, 8, 964–993

- ^ Grant, D. L. (2008). Collaborative Solutions to Colorado River Water Shortages: The Basin States’ Proposal and Beyond. Nevada Law Journal, 8, 964–993

- ^ Mulroy, P. (2008). Beyond The Divisions: A Compact That Unites. Journal of Land, Resources, and Environmental Law, (1), 105–117

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ Weissenstein, M. (2001, April 9). The Water Empress of Vegas: How Patricia Mulroy quenched Sin City’s Thirst. High County News. Retrieved from: http://www.hcn.org/issues/200/10404

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

- ^ Nevada Division of Water Resources. (1992). Nevada Water Facts. Retrieved from: http://www.pg-tim.com/files/NV_Water_Facts.pdf

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

| Agreement | Colorado River Compact +, 2007 Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations +, 1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty + and Minute 319 + |

| Area | 637,000 km² (245,945.7 mi²) + |

| Climate | Arid/desert (Köppen B-type) + |

| Geolocation | 36° 9' 49.284", -115° 11' 25.4328"Latitude: 36.16369 Longitude: -115.190398 + |

| Issue | Urban allocation and demand management +, Managing shortages in the Colorado River +, Urban purchase of rural groundwater rights + and Groundwater withdrawals and ecosystem impacts + |

| Key Question | How can consultation and cooperation among stakeholders and development partners be better facilitated/managed/fostered? + |

| Land Use | urban + |

| NSPD | Water Quantity +, Governance +, Ecosystems + and Values and Norms + |

| Population | 30,000,000 million + |

| Riparian | Nevada (U.S.) +, Arizona (U.S.) +, California (U.S.) +, Colorado (U.S.) +, New Mexico (U.S.) +, Utah (U.S.) +, Wyoming (U.S.) + and Mexico + |

| Stakeholder Type | Local Government +, Federated state/territorial/provincial government +, Sovereign state/national/federal government +, Environmental interest + and Community or organized citizens + |

| Water Feature | Colorado River + |

| Water Use | Domestic/Urban Supply +, Other Ecological Services + and Recreation or Tourism + |

| Has subobjectThis property is a special property in this wiki. | Water Competition & Cooperation in the Las Vegas Valley + |

This is the

This is the