Water Competition & Cooperation in the Las Vegas Valley

| Total Population | 3030,000,000 millionmillion |

|---|---|

| Total Area | 637000637,000 km² 245,945.7 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Arid/desert (Köppen B-type) |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | urban |

| Important Uses of Water | Domestic/Urban Supply, Other Ecological Services, Recreation or Tourism |

| Water Features: | Colorado River |

| Riparians: | Nevada (U.S.), Arizona (U.S.), California (U.S.), Colorado (U.S.), New Mexico (U.S.), Utah (U.S.), Wyoming (U.S.), Mexico |

| Agreements: | Colorado River Compact, 2007 Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations, 1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty, Minute 319 |

Contents

Summary

The Las Vegas Valley, which includes the city of Las Vegas and the surrounding municipalities, is located in the Mojave Desert in Southern Nevada. Like most desert cities, Las Vegas exists because of water; the artesian springs of the Las Vegas Valley provided an ample water supply for Native Americans, ranchers and later a small railroad city. However, population growth increased demands far beyond local supplies. The area now depends on the Colorado River for the majority of its water supply. Natural scarcity, population growth and climate variability all contribute to the Valley’s water management challenges. This analysis addresses the following questions: 1) How can cooperation lead to better water demand management? 2) What conditions enable effective cooperation? The case demonstrates that a well-structured cooperative agency can prompt joint action by decreasing competition over water supplies. The Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA), a regional water utility made up of five water suppliers, was formed out of the water crisis that stuck the Las Vegas Valley in the late 1980s. Although the scarcity was key enabling condition for the creation of the SNWA, the transition would not have been as successful without the strong leadership present. Since its formation, the SNWA has fostered cooperation among the five water suppliers and contributed to substantial per capita demand reductions. However, as population growth continues and climate change exacerbates natural variability, the SNWA and its members will need to adapt to continue providing reliable water supply.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

The Las Vegas Valley is located in the Mojave Desert in Southern Nevada and receives about 10 cm (4 inches) of rainfall a year. Area municipalities rely on both groundwater and the Colorado River for water supply. Fast growing urban areas and a booming tourism industry have stressed water supplies. Natural climate variability with periodic droughts has further challenged water providers; projected climate changes will exacerbate these challenges.

Demographics

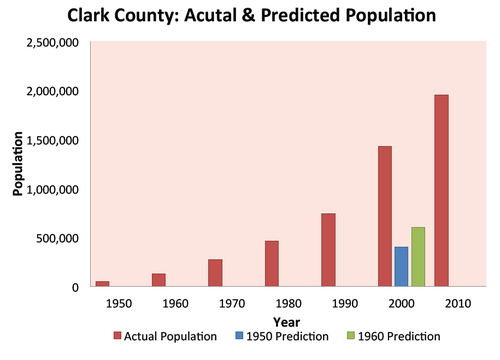

American settlement of Las Vegas began in 1855 when a group of Mormons built a settlement based around irrigated agriculture [1]. Soon after the Mormons abandoned the valley but ranching and irrigated agriculture continued. The town of Las Vegas was formed in 1905 as a railroad way station [2]. At the beginning of the 19th century, Las Vegas was a typical small western town. It grew rapidly in the 1920’s and 30’s, fueled by federal spending and an influx of workers for the Hoover Dam; government spending again fueled growth in the 1950’s as atomic testing and military training was conducted outside Las Vegas [3]. The rapid growth continued into the early 2000’s with Las Vegas being the fastest growing city, in the fastest growing state since World War II as seen in Figure 1 [4]. In addition to rapid population growth, Las Vegas has been a significant tourist destination since the 1930’s. Gambling was legalized in the 1931 and by 1935 Las Vegas was already established as a marriage destination due to California’s three day waiting period for a marriage license; Hoover Dam attracted new visitors and tourism further expanded in 1941 with the start of the resort industry [5]. Tourism continued to grow and Las Vegas saw a huge boom in tourism with annual visitors steadily increasing from 1970 until the mid-1990’s as seen in Figure 2 [6].

File:Clark County Population Growth 1950 - 2010.png

Issues and Stakeholders

Urban allocation and demand management

NSPD: Water Quantity, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Local Government

The four municipalities, Las Vegas, North Las Vegas, Henderson and Boulder City, along with Nellis Air Force Base and Clark County, are connected through their shared water supply. They collectively use the majority of Nevada’s Colorado River allocation and share an interconnected aquifer system. In order to regionally manage water, the five suppliers combined their water rights and got rid of the system of priority rights [7]. While each utility runs its own operations, infrastructure, conservation and planning were implemented by the SNWA regionally and each municipality and county covered by the SNWA is also required to follow the agreed upon conservation standards [8]. They have so far made substantial progress in controlling demands through cooperation having reduced per capita demands from 350 gallons per day in 1990 to 250 gallons per day in 2008 [9]. With some of the easiest conservation measures already taken, tougher changes may be required to meet future conservation goals.

Stakeholders

- SNWA and associated utilities and municipalities

- Associated utilities

- Big Bend Water District

- Clark County Water Reclamation

- Las Vegas Valley Water District

- Associated municipalities

- City of Las Vegas

- City of North Las Vegas

- City of Henderson

- City of Boulder City

- Nellis Air Force Base

- Clark County

Managing shortages in the Colorado River

NSPD: Water Quantity, Ecosystems, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Sovereign state/national/federal government, Local Government, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens

The Colorado River Compact allocated flow based on 22 year record of river flows which suggested that a flow of 16,500,000 was a conservative estimate; however, the natural average annual flow in the Colorado was just 15,000,000 ac-feet for hundred years from 1906 to 2006 [10]; [11]. Since the compact was written USBR flow estimates show that during several periods, average annual flows did not reach the allocated flow.

In response to the Colorado River Basin drought in the early 2000s, the seven basin states developed a proposal outlining shortage operations, the Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations, which was later adopted by the Secretary of the Interior [12]. The interim guidelines are set to expire in 2026 and, given the historical record and the regional climate projections, shortages will likely increase. Minute 319, a 2012 interim agreement between the United States and Mexico, states “both countries have recognized the value of an interim period of cooperation to proactively manage the Colorado River in light of historical and potential future increased variability due to climate change” [13]. The agreement outlines new guidelines for the distribution of flows during surplus and shortage conditions and outlines provisions for increased water for the environment in Mexico. The 2007 Interim Guidelines for Colorado River Operations and Minute 319 are both a step towards adapting the management of the Colorado River. However, both measures are temporary and the stakeholders within the states will likely need to renegotiate shortage rules in the future. Although the seven states and Mexico cooperated to develop the Interim Guidelines and Minute 319, they disagree in their interpretations of the various elements of the Law of the River including on how to determine deficit conditions and the legality of selling water across basin lines [14]. In addition to future climate and demand patterns, the resolution of these legal disagreements will affect the water availability in each of the basin states.

Stakeholders

- Lower basin states

- Arizona

- California

- Nevada

- Upper Basin States

- Colorado

- New Mexico

- Utah

- Wyoming

- Mexico

- SNWA and associated utilities and municipalities

- Water users within the other basin states

Urban purchase of rural groundwater rights

NSPD: Water Quantity, Governance, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Community or organized citizens

Despite conservation efforts and improved allocation schemes, local water resources and the Colorado River allocation are not sufficient to guarantee water supplies for urban and suburban Sothern Nevada. Therefore SNWA’s long-term plans also include: formulating a water resources plan that utilizes all available supplies including applying for use of un-appropriated groundwater located in other areas of Nevada [15]. The problem of water resource availability has been defined by the regional water utilities and their constituents and the SNWA has been successful in dealing with the problem as defined. The SNWA has been effective at coordinating water management within the five municipalities and Clark County; however, the impacts of its plans extend beyond the urban areas of Southern Nevada to rural residents and desert ecosystems. The SNWA filled 147 permits for groundwater application in 1989 in 30 different basins [16]. The “water grab”, as it was known in the rural counties, instigated an instant backlash [17]. Due to environmental concerns and existing appropriations the SNWA withdrew, transferred or declined to pursue 49 applications, limiting their requests to 21 different basins [18]. In addition to existing groundwater rights, there are concerns over how withdrawals may impact spring discharges and therefore surface water rights [19]. In 2003, SNWA developed an agreement with Lincoln County to resolve outstanding concerns over groundwater applications within the county [20].

Stakeholders

- SNWA and associated utilities and municipalities

- Rural municipalities

- Rural water rights holders

Groundwater withdrawals and ecosystem impacts

NSPD: Water Quantity, Ecosystems, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens

Despite the withdrawal of some of SNWA’s most controversial groundwater applications, environmental critiques remain. Deacon and colleagues [21], caution that the groundwater withdrawals planned by the SNWA present an underappreciated threat to the spring ecosystems and the species which depend on them. Twenty of those impacted species are listed under the federal Endangered Species Protection Act [22]. The SNWA as well as several independent researchers developed groundwater models to determine the probable future effects of groundwater development. All of the independent models showed significant declines in the effective basins except for the SNWA model which assumed higher levels of recharge due to precipitation [23]. In addition to varying assumptions on model parameters, there is disagreement on the proper method of calculating perennial yield. The Nevada Division of Water Resources defines perennial yield as “the amount of water from a ground-water aquifer that can be economically withdrawn for an indefinite period of time… and does not exceed the natural recharge” [24]. This definition allows the reductions in spring flows and decreases groundwater elevation that can cause detrimental impacts to plant and animal species [25]. Discrepancies in perennial yield definitions and modeling assumptions have not yet been resolved.

Stakeholders

- SNWA and associated utilities and municipalities

- Environmental groups

- Groundwater dependent species

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:Formation of the SNWA: Cooperation in Demand Management

The formation of the Southern Nevada Water Authority stems from the stakeholders recognition of their interdependence. This case demonstrates that stakeholders need for cooperation, and therefore their willingness to cooperate, increases in proportion to the stresses on the system. It also demonstrates that good leadership was instrumental to the success of the Authority in controlling water demands and acquiring water supplies.(read the full article... )

Contributed by: Margaret Garcia (last edit: 20 May 2013)

Key Questions

Balancing Industries & Sectors: How can consultation and cooperation among stakeholders and development partners be better facilitated/managed/fostered?

In the Las Vegas Valley, municipalities competing for a limited water supply led to great inefficiencies. The formation of a cooperative water management utility created incentives for conservation and led to decreased water demands. Serious near-term shortages sparked interest in cooperation but good leadership was critical in navigating the transition.

External Links

- Las Vegas: Landsat Annual Timelapse 1984-2012 — Timelapse of Las Vegas area urban growth.

- Las Vegas Valley Water District — Website for the Las Vegas Valley Water District

- Southern Nevada Water Authority — Website for the Southern Nevada Water Authority

- US Bureau of Reclamation: Law of the River — USBR website outlining the numerous compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, contracts, and regulatory guidelines collectively known as the "Law of the River."

- ^ Harrison, C. (2009). Water use and natural limits in the Las Vegas Valley: A history of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. University of Nevada, Las Vegas

- ^ Douglass, W. a., & Raento, P. (2004). The Tradition of Invention: Conceiving Las Vegas. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(1), 7–23. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2003.05.001

- ^ Jones, F. L., & Cahlan, J. F. (1975). Water: a history of Las Vegas. Las Vegas Valley Water District

- ^ Douglass, W. a., & Raento, P. (2004). The Tradition of Invention: Conceiving Las Vegas. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(1), 7–23. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2003.05.001

- ^ Jones, F. L., & Cahlan, J. F. (1975). Water: a history of Las Vegas. Las Vegas Valley Water District

- ^ Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority (2013). Historical Las Vegas Visitor Statistics: 1970 to 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.lvcva.com/includes/content/images/media/docs/Historical-1970-to-2012.pdf

- ^ Mulroy, P. (2008). Beyond The Divisions: A Compact That Unites. Journal of Land, Resources, and Environmental Law, (1), 105–117

- ^ Harrison, C. (2009). Water use and natural limits in the Las Vegas Valley: A history of the Southern Nevada Water Authority. University of Nevada, Las Vegas

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ Morris, R., Devitt, D. A., Crites, Z. A. M., Borden, G., & Allen, L. N. (1997). Urbanization and Water Conservation in Las Vegas Valley, Nevada. Journal of Water Resources Planning & Management, (123), 189–195

- ^ Grant, D. L. (2008). Collaborative Solutions to Colorado River Water Shortages: The Basin States’ Proposal and Beyond. Nevada Law Journal, 8, 964–993

- ^ Grant, D. L. (2008). Collaborative Solutions to Colorado River Water Shortages: The Basin States’ Proposal and Beyond. Nevada Law Journal, 8, 964–993

- ^ International Boundary and Water Commission (2012, November). Minute 319: Interim International Cooperation Measures in the Colorado River Basin Through 2017 and Extension of Minute 318 Cooperative Measures to Address the Continued Effects of the April 2010 Earthquake in the Mexicali Valley, Baja California. Retrieved from: http://www.ibwc.gov/Files/Minutes/Minute_319.pdf

- ^ Grant, D. L. (2008). Collaborative Solutions to Colorado River Water Shortages: The Basin States’ Proposal and Beyond. Nevada Law Journal, 8, 964–993

- ^ Mulroy, P. (2008). Beyond The Divisions: A Compact That Unites. Journal of Land, Resources, and Environmental Law, (1), 105–117

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ Weissenstein, M. (2001, April 9). The Water Empress of Vegas: How Patricia Mulroy quenched Sin City’s Thirst. High County News. Retrieved from: http://www.hcn.org/issues/200/10404

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

- ^ Southern Nevada Water Authority [SNWA]. (2009). Water Resources Plan 09. Retrieved from: http://www.snwa.com/ws/resource_plan.html

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience

- ^ Nevada Division of Water Resources. (1992). Nevada Water Facts. Retrieved from: http://www.pg-tim.com/files/NV_Water_Facts.pdf

- ^ Deacon, J. E., Williams, A. E., Williams, C. D., & Williams, J. E. (2007). Fueling Population Growth in Las Vegas : How Large-scale Groundwater Withdrawal Could Burn Regional Biodiversity. BioScience