Northeast Regional Ocean Planning

| Geolocation: | 42° 36' 0", -69° 30' 0" |

|---|---|

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | religious/cultural sites |

| Important Uses of Water | Fisheries - wild, Fisheries - farmed, Industry - non-consumptive use, Other Ecological Services, Recreation or Tourism |

Contents

Summary

With new ocean uses emerging off the coasts, changing ocean dynamics, and a complex ocean regulatory framework, the Northeast was poised for increased ocean management conflicts. From regional level efforts to the National Ocean Policy, the climate was ripe for parties to come together and improve coordination to prevent future conflicts. State, federal, and tribal representatives with ocean management mandates formed the Northeast Regional Planning Body to mitigate future ocean use conflicts through providing a more comprehensive, stakeholder driven, and long-term vision for the New England coastline and ocean. In addition, the process provided a new publicly accessible online portal for bringing together ocean use data. The portal ultimately would help regulators, stakeholders, and project developers share data for more informed and transparent decision-making. Ultimately, the ocean planning process provides a stronger foundation for the regional to navigate future multi-use ocean conflicts.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

A. Background

The New England coastline has long been a source of bustling commerce, vibrant fisheries, and culture intertwined with the ocean. Given the region’s rich history and many ocean resources, it is not surprising that the Northeast became the first region to begin more comprehensive ocean planning in the United States. There are a number of conditions in the more recent history of the region that made it especially ripe for this process.

The 2001 proposed Massachusetts Cape Wind Project became a significant ocean use controversy. The proposed windfarm off the coast of Massachusetts became embroiled in litigation and push back from local citizens who did not support the project location. The developer ultimately spent years working through federal and state permitting processes and dealing with costly litigation. In total, seventeen different agencies were responsible for reviewing and granting permits on the project. As of June 2017, the company is just reaching the financing and final commercial contracting stage for the project. The inordinately lengthy process has been an example for many on the potential benefits of ocean planning to mitigate such ocean use conflicts.

In 2005, as the Cape Wind controversy unfolded in the region, the New England state governors formed the Northeast Regional Ocean Council (NROC) as a regional forum to facilitate a more coordinated response to ocean and coastal issues. Federal agencies were eventually brought into the forum as parties recognized that coordination with national entities was important for success. In addition to this increased communication and coordination, both Massachusetts and Rhode Island took initiative within their own states to create a state level ocean plan.

In May 2008, the Massachusetts Oceans Act was passed as a comprehensive ocean planning law for the state. The law required the development of a statewide plan to manage development while balancing conservation with traditional and new uses, including renewable energy. Shortly after, Rhode Island developed an Ocean Special Area Management Plan (SAMP) to define ocean use zones, based upon the best available science as well as public input and involvement.

At the same time, as regional dynamics were shifting to improve ocean management, the Obama Administration passed Executive Order 13547—the National Ocean Policy (NOP). The National Ocean Policy called for “a comprehensive and collaborative framework for the stewardship of the ocean, our coasts, and the Great Lakes.” In building upon existing regional ocean management work, it importantly provided a mandate to federal agencies to engage with regional level planning efforts within their regulations, and also brought federally recognized tribes to the table as important resource managers.

B. What is the Conflict?

The key conflict driver that brought parties together in the Northeast ocean planning process was tension between traditional and new ocean uses, along with general dissatisfaction with the ocean management process. In many ways, the Massachusetts Cape Wind project encapsulated this emerging tension as renewable energy development off the coast became an increasing reality. Frustration in some cases ran high as companies sought viable project proposals. Needing various permits, federal and state reviews, and having pushback or litigation led by citizens were costly hurdles.

In addition, both companies and citizens grew frustrated with the maze of, seemingly disconnected, state and federal processes. In the Cape Wind project alone, a total of seventeen different agencies were responsible for reviewing and granting permits. Not only was this framework challenging for developers, but also for the public who did not have a clear way to engage in a coordinated review process. This challenge of ocean management is not confined to just the Northeast region. The United States, which has the largest ocean area of any country in the world, has over 3.4 million square nautical miles with at least 20 federal agencies and 140 federal statutes overseeing the management of that resource, not to mention state or local regulations as well.

Given this challenge, the National Ocean Policy presented a catalytic opportunity to mitigate such future conflicts by seeking to increase management efficiency, maximize ocean use compatibilities, and provide a foundation of shared data for all users to access in decision-making. The ultimate challenge was to proactively try to balance traditional and new ocean uses in the future of the Northeast coastline. Substantively, this meant ensuring economic development—fisheries, aquaculture, resource extraction, renewables, and marine transport—alongside ecosystem protection—sustainable fishery management, conservation, endangered species—and with a balanced consideration of cultural resources and recreational needs. At the same time, the Northeast coast and ocean resources were seeing changing dynamics due to climate change and research was needed to help inform balanced decisions.

Ultimately, this emerging area of potential conflict offered an opportunity to bring federal, state, and tribal regulatory authorities together to increase coordination, improve and share data, and understand stakeholder interests within a longer-term vision for the future of the Northeast ocean.

C. Who are the Stakeholders?

As called for in the National Ocean Policy, the Northeast set-up a Regional Planning Body (RPB) charged with developing and implementing a Northeast Ocean Plan. These were the key decision-makers at the table who ultimately had various regulatory and management responsibilities within their existing mandates. They include:

States

-Connecticut

-Department of Energy and Environmental Protection

-Maine

-Department of Marine Resources

-Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry

-Massachusetts

-Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs/Coastal Zone Management

-Division of Marine Fisheries

-New Hampshire

-Department of Environmental Services

-Department of Fish and Game

-Rhode Island

-Coastal Resource Management Council

-Department of Environmental Management

-Vermont

-University of Vermont

Federal Agencies

-Joint Chiefs of Staff -U.S. Department of Agriculture -U.S. Department of Commerce -U.S. Department of Defense -U.S. Department of Energy -U.S. Department of Homeland Security -U.S. Department of Interior -U.S. Department of Transportation -U.S. Environmental Protection Agency -Federal Energy Regulatory Commission -New England Fishery Management Council

Tribes

-Aroostook Band of Micmacs/All Nations Consulting

-Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians

-Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation

-Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Council

-Mohegan Indian Tribe of Connecticut

-Passamaquoddy Tribe- Indian Township Reservation

-Penobscot Indian Nation

-Narragansett Indian Tribe of Rhode Island

-Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

Ex-Officio Members

-New York

-Division of Coastal Resources

-Canada

-Fisheries and Oceans Canada

In addition, there were many stakeholders who use, or intend to use, ocean resources and were engaged throughout the process. The RPB carried out stakeholder engagement to ensure their interests and needs informed the ocean planning process. These stakeholders, broadly, include:

-Commercial fishers -Recreational fishers -Aquaculture companies and users -Marine transport companies and users -Scientists and researchers -Environmental and conservation organizations -Renewable energy companies -Oil, gas, and extractive resource companies -Recreational users (boaters, beach front owners, scuba dives, surfers, etc.)

D. What did they do to resolve the Conflict?

The creation of the Northeast Regional Planning Body (NE RPB) was a national and regional response to the challenges of ocean management. The effort aimed at mitigating future ocean use conflicts and providing a more comprehensive and long-term vision for the New England coastline and ocean. It did not retroactively address previous conflicts, such as Cape Wind which was already moving through litigation. Rather, it sought to learn from such ocean use conflicts and improve future management.

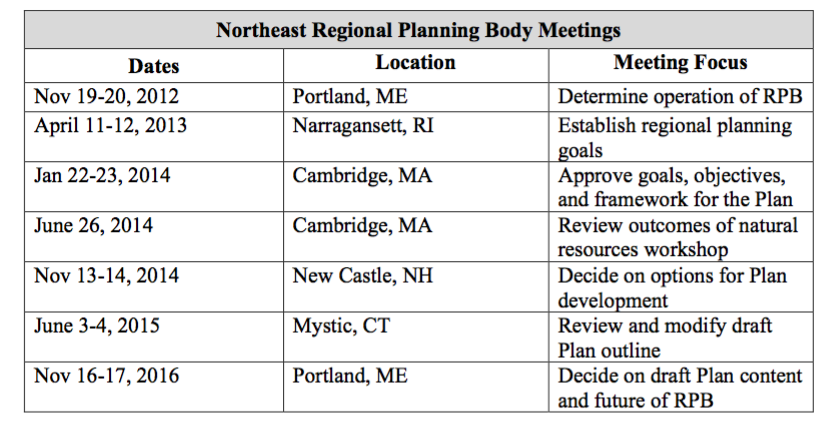

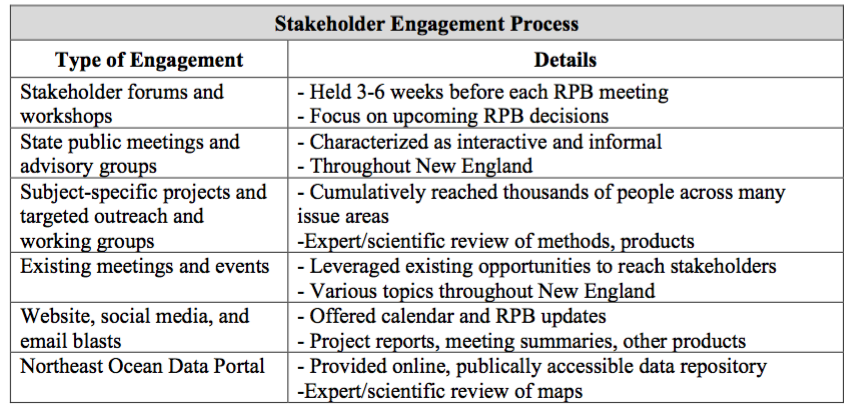

The ocean planning processed included a number of NE RPB meetings, open to the public, as well as tailored stakeholder engagement efforts. The tables below summarize both parts of the process:

The Northeast Regional Planning Body was initially tasked with establishing their working structure and process, which built upon the previous work in the region (NROC, MA Oceans Act and RI Ocean SAMP). From the initial meeting, Meridian Institute, provided neutral third-party facilitation and process support for the RPB. The ocean planning process evolved to focus on both drafting a comprehensive regional ocean plan and creating a Northeast ocean data portal.

The goal in creating a regional ocean plan was to provide an upstream vision informed by stakeholder engagement and the best available data. This would ultimately help ocean users and management agencies understand conflicting needs and how to best approach them. In addition, it became clear to parties that current ocean data was scattered between various agencies and entities. In order to best inform ocean planning and coordinate decision-making, parties decided that all data needed to be publicly accessible through one online portal. These two products, the ocean plan and data portal, became the foundation of discussions and work within the Northeast ocean planning process. The Northeast Ocean Plan identified three goals that drove their work: 1) healthy ocean and coastal ecosystems 2) effective decision-making and 3) compatibility among past, current, and future ocean uses. The final Plan was organized by key ocean uses raised throughout the ocean planning process with stakeholders. Those include:

-Marine life and habitat -Cultural Resources -Marine transportation -National Security -Commercial and Recreational Fishing -Recreation -Energy and Infrastructure -Aquaculture -Offshore sand resources -Restoration

Each ocean use area in the Plan was informed by consultation with stakeholders, an exploration of research and data, and agency responsibilities in managing these resources. Together, the Plan strives to build a comprehensive overview of where these ocean uses intersect with one another and with regulations. It also outlines the relevant data available, as well as identifies areas were additional research and understanding is needed, especially regarding emerging ocean uses. It does not zone or determine how to allocate resources, but rather helps put ocean uses together in a more comprehensive view for managers and local stakeholders.

The Northeast data portal is accessible online here: http://www.northeastoceandata.org. It allows any user to access a number of data sources and map layers relevant to ocean management. The goal for this publicly accessible data is to help reduce potential conflicts. It provides regulators and decision-makers with the same agreed upon data, and any potential developer has access early on to that same data. Ideally, this will help inform future projects, such as offshore wind, to help ensure that even the initial proposed location is more amenable not just to the business, but in consideration of multiple ocean uses and stakeholders.

The data portal is also managed and maintained by a multi-stakeholder work group that will work to ensure it is an accurate and growing resource. They invite other stakeholder groups and organizations to reach out to them if interested in collaborating on the initiative.

Overall, the Northeast ocean planning process, data portal, and Northeast Ocean Plan provide a stronger foundation for navigating potential multi-use ocean conflicts in the future. It does not fully resolve all potential conflicts, but it provides an enhanced working relationship among stakeholders and decision-makers that will likely help mitigate conflicts. As the Ocean Plan states:

“New England’s maritime environmental history offers a valuable lesson: it is much better to be proactive than to try to resolve problems after the fact. Both the environment and humanity benefit from such proactive behavior, not only in the form of a healthier ecosystem, but also as a result of economic savings. The Plan is based on this very simple, yet powerful, philosophy. By encouraging foresight and the improved coordination and planning such an approach necessitates, the Plan is designed to help the region with its management decisions, as the Northeast simultaneously explores new ocean uses, such as wind energy, and protects this rapidly changing environment.”

Although the first iteration of the Plan is complete, the Regional Planning Body will continue to meet twice a year to ensure successful plan implementation, continue to engage stakeholders and ensure the Plan reflects the Northeast’s evolving ocean vision and needs, and update and gather new data for the ocean portal.

E. Future Challenges

Moving forward, the Northeast Regional Planning Body will have two central challenges to address in the near term. They will need to ensure sustainable funding and work to become a learning organization.

In regards to funding, up until now, philanthropic foundations and organizations have been one of the primary funding sources for the ocean planning process. Although it was originally envisioned that federal ocean management agencies would support the process within their own budgets and roles, Congress has restricted agencies from using funds towards this policy. Some congressional representatives have raised concerns that the National Ocean Policy is an overreach of executive authority and could be an additional bureaucratic burden. Given the Northeast’s success thus far with the process, previous regional coordination, and state ocean plans, it is unlikely that national politics will be an obstacle for continued regional work. It could, however, continue to be a barrier on any funding support from federal agencies. Philanthropic organizations may continue to support the effort for a while, but without finding a sustainable mechanism or ways to streamline costs, it could be a challenge.

As the Northeast Regional Planning Body turns toward implementing the ocean plan, intentional reflection and organizational learning will also be key. As projects and management decisions arise, the NE RPB should periodically have facilitated discussions on what is working well towards their goals—1) healthy ocean and coastal ecosystems 2) effective decision-making and 3) compatibility among past, current, and future ocean uses)—and what could be improved. In achieving this, it could be helpful for a third party to help them with a mid-point stakeholder assessment. In addition, as staff turns over in state, federal, and tribal agencies it will be important for them to be trained in the ocean planning resources/process, including the data portal and knowing their fellow agency counterparts.

F. Water Diplomacy Framework Reflections

The Northeast ocean planning process encompassed a number of key elements of the Water Diplomacy Framework that helped ensure its success and will be important to regional ocean planning work going forward.

Appropriate Stakeholder Representation:

The NE RPB itself is comprised of key federal, state, and tribal representation that encompasses collective regulatory and ocean management authority. However, the process also ensured that it was not just those with authority informing ocean planning, but rather the range of ocean users and stakeholders themselves. The very first meeting of the NE RPB in 2012 was met with a mix of enthusiasm and skepticism from stakeholders. One of the key questions during the public comment section was how is this going to impact us and how can we have a voice in the process. From that initial public comment session, the NE RPB worked to expand their efforts to ensure meaningful engagement from a wide range of stakeholders.

The Northeast ocean planning process identified this as a key principle, striving to ensure “meaningful public participation—reflect the knowledge, perspectives, and needs of ocean stakeholders— fishermen; scientists; boaters; environmental groups; leaders in the shipping, ports, and energy industries—and all New Englanders whose lives are touched by the ocean.” The NE RPB prioritized engaging appropriate stakeholders and openly sought feedback from stakeholders, as well as professional support from the Consensus Building Institute, to ensure their engagement approach was as effective as possible.

As section D above outlines, the NE RPB leveraged a range of engagement methods to ensure meaningful and appropriate engagement throughout the process. They held stakeholder forums and workshops 3-6 weeks in advance of NE RPB meetings and used those to focus on input in upcoming decisions. All NE RPB meetings were open to the public, had online meeting summaries, as well as video recordings in some cases. In addition, the NE RPB held public meetings in every Northeast state that was facilitated by a third-party mediation team and helped ensure informal but meaningful dialogue between NE RPB members and stakeholder groups. The NE RPB also had subject specific and targeted outreach that was especially important in gathering data and information, public input, and scientific expertise around the 10 identified ocean resources and activities. The ocean planning process also leveraged existing meetings and events around ocean issues throughout the region to speak with stakeholders, and they also coordinated online outreach to inform and engage stakeholders.

Overall, the stakeholder representation and engagement in the Northeast ocean planning process seems quite positive. As one meeting summary for public engagement in 2016 summarized, “the ocean planning effort has engaged a variety of stakeholder and generated useful data. Participants shared positive comments about the planning effort and the Plan overall. They expressed appreciation towards the RPB for engaging with diverse groups of stakeholders, and noted the wealth of helpful new information on ocean ecology and uses produced through the planning effort. They expressed hope that the stakeholder engagement and data-gathering efforts associated with the Plan would continue, and improve, moving forward.”

During the same set of meetings, however, participants did highlight the need to improve engagement with particular stakeholder groups, such as fisherfolks and working waterfront communities. It is clear that the NE RPB will need to continue to seek feedback and improve their stakeholder engagement efforts as they move forward with plan implementation. If there are key stakeholders who are still unable to effectively engage in the process, the NE RPB should consider their specific needs in relation to meeting locations and times, accessibility of information both in location and readability, and overall how the process could be better tailored to ensure their input. Nonetheless, for such a large region with many diverse stakeholders, the overall ocean planning process was historic in its level of engagement and sets a strong precedence and foundation for improved ocean management.

Joint Fact Finding:

The Northeast ocean data portal is a result of a joint fact finding process that not only brought together existing data, but also identified information gaps and helped prioritize research needs for the region. Through a series of workgroups and engagement with stakeholders, the NE RPB was able produce peer-reviewed maps and data characterizing the central ocean resources outlined in the Ocean plan. In addition to what was produced through the ocean planning process thus far, the NE RPB worked with stakeholders to identify key research needs going forward. Joint fact finding will likely remain a key tenant of the ocean planning process going forward as parties continue to work on filling information gaps.

Third-party neutral/mediation:

The Water Diplomacy Framework emphasizes the role a third-party neutral or mediator can play in helping parties reach consensus on water management issues. In the NE RPB process, third-party support was instrumental throughout. The Meridian Institute provided facilitation for the NE RPB meetings from the very beginning. As the NE RPB turned towards stakeholder engagement, they brought on the Consensus Building Institute to facilitate and help design the stakeholder engagement process. This offered the NE RPB the opportunity to work with experts in expanding their range of approaches to engagement and ensure that dialogue was well facilitated.

In addition, early on, a number of NE RPB members joined the U.S. Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution for an online training and discussion on principles for stakeholder engagement. This helped to build capacity among RPB members in thinking about how to effectively engage stakeholders and the importance of appropriate representation.

Adaptive Management:

The Northeast Ocean Plan strives to embody an adaptive management approach. One of their key principles driving the Plan is “adaptive management—update decisions as we learn more about patterns of ocean uses, and as environmental, social, and economic conditions change.” In regards to implementation, the Plan incorporates this approach through monitoring and evaluation, continued meetings that will allow for refined or new approaches to the Plan, and a focus on improving scientific data to inform management. Unlike the elements above, adaptive management has not yet really been carried out as part of the ocean planning process. However, by having a central focus both throughout the process and in the Plan, there is a strong foundation for successful adaptive management going forward.

All of these elements have been important to the success of the Northeast ocean planning process thus far. It will be important for the NE RPB to continue to incorporate appropriate stakeholder representation, joint fact finding, third-party neutral support, and adaptive management going forward. As the NE RPB works to become a learning organization, it should consider these areas for reflection and improvement as their work evolves.

Issues and Stakeholders

How can coordination be improved for regulatory and management decisions?

NSPD: Governance, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Environmental interest, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens

How can data be more accessible and shared for better decision-making?

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Ecosystems, Governance, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Environmental interest, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens

What additional areas of research and data are needed to further inform ocean management in the Northeast?

NSPD: Ecosystems, Governance, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Environmental interest, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreNo ASI articles have been added yet for this case

Key Questions

Integration across Sectors: How can consultation and cooperation among stakeholders and development partners be better facilitated/managed/fostered?

As the case overview outlines, the Northeast Regional Ocean Planning Process had a robust stakeholder engagement process. The process included different methods and meetings for stakeholders to get involved, different locations, and different levels of engagement.

Perhaps most notable in this case, the stakeholder engagement process was integrated into the ocean planning process from early on. It was not just a one stop check box for general input, but a thoughtful and coordinated approach throughout every phase of planning. This is a valuable lesson for other processes as it helped ensure stakeholders were engaged early on and had meaningful input throughout.

If the Northeast Regional Planning Body had not integrated such engagement throughout, it is unlikely that their final Plan would be as widely supported. Often times, in such circumstances, stakeholders instead feel they are asked to rubber stamp something that has already been decided. By engaging early on, incorporating feedback throughout, and continuing to dialogue, the Northeast ocean planning process was more effective in their stakeholder engagement.

In addition, the engagement process was facilitated by third-party neutrals which allowed for productive and meaningful conversations between decision-makers on the NE RPB and the broader community of ocean users. The third-party neutral team also provided neutral documentation of the meetings that allowed all parties to be on the same page with what feedback needed to be incorporated into the planning process.

Power and Politics: How do national policies influence water use at the local level?

In the case of the Northeast ocean planning process, the National Ocean Policy was certainly a driving factor in helping to catalyze improved regional coordination that built off of existing state level initiatives. When the National Ocean Policy was created, the Northeast already had two state-level ocean plans and a regional ocean council working to improve coordination on ocean management.

The national level policy helped bring federal agencies to the table with a clear mandate from the Executive branch to focus on supporting regional ocean planning. In addition, it helped bring tribal governments to the table as an important resource in planning, technical ecological knowledge, and cultural resources. Having increased leadership and collaboration from both federal and tribal representatives, overall improved the ocean management work in the Northeast.

Perhaps most importantly with this national initiative, it encouraged regions to help drive the process and tailor their needs from the bottom-up. It did not create additional regulatory requirements, but instead encouraged existing entities to improve their work through increased coordination and stakeholder input towards a collective future vision of ocean management.

Transboundary Water Issues: What considerations can be given to incorporating collaborative adaptive management (CAM)? What efforts have the parties made to review and adjust a solution or decision over time in light of changing conditions?

Although parties have not yet adjusted their Northeast Ocean Plan to adaptive management needs, the Plan prioritizes this in future work. Adaptive management was a key principle for the planning process and central in the Ocean Plan. In prioritizing this, parties also focused on research needs and information gaps as priorities to inform future work. This will ideally help shape future adaptive management work. Integrating collaborative adaptive management into the planning process and future meetings for implementation are positive approaches for success.

Tagged with: ocean planning marine ecosystem national ocean policy adaptive management stakeholder engagement

References

Angela T. Howe, The U.S. National Ocean Policy: One Small Step For National Waters, But Will It Be The Giant Leap Needed For Our Blue Planet, 17 Ocean & Coastal L.J. (2011). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/oclj/vol17/iss1/4

Cape Wind. (2017). Cape Wind Project Status and Timeline. Retrieved from https://www.capewind.org/when

Consensus Building Institute. (2016). Northeast RPB Public Listening Sessions on the Draft Northeast Regional Ocean Plan. Retrieved from http://neoceanplanning.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Summary-of-Public-Listening-Sessions.pdf

Meridian Institute. (2012). Summary of Discussions: Northeast Regional Planning Body Inaugural Meeting. Retrieved from http://neoceanplanning.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/RPB-Meeting-Summary-Nov-2012.pdf

Northeast Regional Ocean Council. (2017). NROC Overview. Retrieved from http://northeastoceancouncil.org/about/nroc-overview/

Northeast Regional Planning Body. (2017). Northeast Regional Planning Body Membership Roster. Retrieved from http://neoceanplanning.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/RPB-Membership-Roster-October-2016.pdf

Northeast Regional Planning Body. (2016). Northeast Ocean Plan. Retrieved from http://neoceanplanning.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Northeast-Ocean-Plan_Full.pdf

O'Brien, C. (2014). Continuing Controversy over Cape Wind: The Lasting Effects of Legal and Regulatory Hurdles on the Offshore Wind Farm. Georgetown International Environmental Law Review 26(4), 411-434. Retrieved from http://heinonline.org.ezproxy.library.tufts.edu/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/gintenlr26&collection=journals&id=445

The White House. (2010). Executive Order 13547 --Stewardship of the Ocean, Our Coasts, and the Great Lakes. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/executive-order-stewardship-ocean-our-coasts-and-great-lakes

U.S. Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution. (2011). Principles for Stakeholder Involvement in Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning. Retrieved from http://projects.ecr.gov/cmspstakeholderengagement/pdf/PrinciplesforStakeholderInvolvementinCoastalandMarineSpatialPlanning_0.pdf