Difference between revisions of "Integrated Management and Negotiations for Equitable Allocation of Flow of the Jordan River Among Riparian States"

| [unchecked revision] | [unchecked revision] |

Mpritchard (Talk | contribs) |

Mpritchard (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|Agreement= | |Agreement= | ||

|REP Framework=[[File:Jordanriverbasin.jpg]] | |REP Framework=[[File:Jordanriverbasin.jpg]] | ||

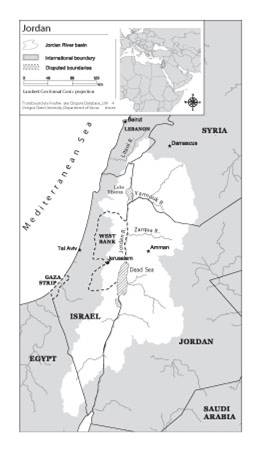

| − | Figure 1. Map of the Jordan River and tributaries (directly and indirectly, including Litani) <ref name = "TFDD 2012">Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) ( | + | Figure 1. Map of the Jordan River and tributaries (directly and indirectly, including Litani) <ref name = "TFDD 2012">Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) (2012). Oregon State University. |

Available on-line at: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu </ref> | Available on-line at: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == The Problem == | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Jordan River flows between five particularly contentious riparians, two of which rely on the river as the primary water supply. By the early-1950s, there was little room for any unilateral development without impacting on other riparian states. The initial issue was an equitable allocation of the annual flow of the Jordan watershed between its riparian states- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Egypt also was included, given its preeminence in the Arab world. Since water was (and is) deeply related to other contentious issues of land, refugees, and political sovereignty. The Johnston negotiations, named after U.S. special envoy Eric Johnston, attempted to mediate the dispute over water rights among all the riparians in the mid-1950s. | ||

| + | Until the current Arab-Israeli peace negotiations, which began in 1991, political or resource problems were always handled separately. Some experts have argued that by separating the two realms of "high" and "low" politics, each process was doomed to fail. The initiatives which were addressed as strictly water resource issues, namely-the Johnston Negotiations of the mid-1950s, attempts at "water-for-peace" through nuclear desalination in the late 1960s, negotiations over the Yarmuk River in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Global Water Summit Initiative of 1991, all failed to one degree or another, because they were handled separately from overall political discussions. The resolution of water resources issues then had to await the Arab-Israeli peace talks to meet with any tangible progress. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Attempts at Conflict Management == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Johnston’s initial proposals were based on a study carried out by Charles Main and the Tennessee Valley Authority at the request of UNRWA to develop the area's water resources and to provide for refugee resettlement. The TVA addressed the problem with a regional approach, pointedly ignoring political boundaries in their study. In the words of the introduction, "the report describes the elements of an efficient arrangement of water supply within the watershed of the Jordan River System. It does not consider political factors or attempt to set this system into the national boundaries now prevailing." | ||

| + | The major features of the Main Plan included small dams on the Hasbani, Dan, and Banias, a medium size (175 MCM storage) dam at Maqarin, additional storage at the Sea of Galilee, and gravity flow canals down both sides of the Jordan Valley. Preliminary allocations gave Israel 394 MCM/yr, Jordan 774 MCM/yr, and Syria 45 MCM/yr. (see Table 1). In addition, the Main Plan described only in-basin use of the Jordan River water, although it conceded that "it is recognized that each of these countries may have different ideas about the specific areas within their boundaries to which these waters might be directed"; and excluded the Litani River. | ||

| + | Israel responded to the "Main Plan" with the "Cotton Plan," which it allocated Israel 1290 MCM/yr, including 400 MCM/yr from the Litani, Jordan 575 MCM/yr, Syria 30 MCM/yr, and Lebanon 450 MCM/yr. In contrast to the Main Plan, the Cotton Plan called for out-of-basin transfers to the coastal plain and the Negev; included the Litani River; and recommended the Sea of Galilee as the main storage facility, thereby diluting its salinity. | ||

| + | In 1954, representatives from Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt established the Arab League Technical Committee under Egyptian leadership and formulated the "Arab Plan." Its principal difference from the Johnston Plan was in the water allocated to each state. Israel was to receive 182 MCM/yr, Jordan 698 MCM/yr, Syria 132 MCM/yr, and Lebanon 35 MCM/yr, in addition to keeping all of the Litani. The Arab Plan reaffirmed in-basin use; excluded the Litani; and rejected storage in the Galilee, which lies wholly in Israel. | ||

| + | Johnston worked until the end of 1955 to reconcile U.S., Arab, and Israeli proposals in a Unified Plan amenable to all of the states involved. His dealings were bolstered by a U.S. offer to fund two-thirds of the development costs. His plan addressed the objections of both sides, and accomplished no small degree of compromise, although his neglect of groundwater issues would later prove an important oversight. Though they had not met face to face for these negotiations, all states agreed on the need for a regional approach. Israel gave up on integration of the Litani and the Arabs agreed to allow out-of-basin transfer. The Arabs objected, but finally agreed, to international supervision of withdrawals and construction. Allocations under the Unified Plan, later known as the Johnston Plan, included 400 MCM/yr to Israel, 720 MCM/yr to Jordan, 132 MCM/yr to Syria and 35 MCM/yr to Lebanon (Table 1). | ||

| + | Although the agreement was never ratified, both sides have generally adhered to the technical details and allocations, even while proceeding with unilateral development. Agreement was encouraged by the United States, which promised funding for future water development projects only as long as the Johnston Plans allocations were adhered to. Since that time to the present, Israeli and Jordanian water officials have met several times a year, as often as every two weeks during the critical summer months, at so-called "Picnic Table Talks" at the confluence of the Jordan and Yarmuk Rivers to discuss flow rates and allocations. | ||

| + | |||

|Issues= | |Issues= | ||

Revision as of 14:57, 31 July 2012

| Geolocation: | 32° 9' 25.245", 35° 33' 6.3281" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 1212,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 4280042,800 km² 16,525.08 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Arid/desert (Köppen B-type), Continental (Köppen D-type), Dry-winter |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban- high density, religious/cultural sites |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation |

Contents

Summary

The Jordan River flows between five particularly contentious riparians, two of which rely on the river as the primary water supply. By the early-1950s, there was little room for any unilateral development without impacting on other riparian states. The initial issue was an equitable allocation of the annual flow of the Jordan watershed between its riparian states- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Egypt also was included, given its preeminence in the Arab world. Until the current Arab-Israeli peace negotiations, which began in 1991, political or resource problems were always handled separately. The initiatives which were addressed as strictly water resource issues, namely-the Johnston Negotiations of the mid-1950s, attempts at "water-for-peace" through nuclear desalination in the late 1960s, negotiations over the Yarmuk River in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Global Water Summit Initiative of 1991, all failed to one degree or another, because they were handled separately from overall political discussions. The resolution of water resources issues then had to await the Arab-Israeli peace talks to meet with any tangible progress. The pace of success of each round of talks has vacillated but, in general, has been increasing. The goal in the Working Group on Water Resources became to plan for a future region at peace, and to leave the pace of implementation to the bilateral talks. This distinction between "planning" and "implementation" became crucial, with progress only being made as the boundary between the two is continuously pushed and blurred by the mediators. Multilateral activities have helped set the stage for agreements formalized in bilateral negotiations-the Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace of 1994, and the Interim Agreements between Israel and the Palestinians (1993 and 1995). For the first time since the states came into being, the Israel-Jordan peace treaty legally spells out mutually recognized water allocations. The Interim Agreement also recognizes the water rights of both Israelis and Palestinians, but defers their quantification until the final round of negotiations.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

Figure 1. Map of the Jordan River and tributaries (directly and indirectly, including Litani) [1]

Figure 1. Map of the Jordan River and tributaries (directly and indirectly, including Litani) [1]

The Problem

The Jordan River flows between five particularly contentious riparians, two of which rely on the river as the primary water supply. By the early-1950s, there was little room for any unilateral development without impacting on other riparian states. The initial issue was an equitable allocation of the annual flow of the Jordan watershed between its riparian states- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Egypt also was included, given its preeminence in the Arab world. Since water was (and is) deeply related to other contentious issues of land, refugees, and political sovereignty. The Johnston negotiations, named after U.S. special envoy Eric Johnston, attempted to mediate the dispute over water rights among all the riparians in the mid-1950s. Until the current Arab-Israeli peace negotiations, which began in 1991, political or resource problems were always handled separately. Some experts have argued that by separating the two realms of "high" and "low" politics, each process was doomed to fail. The initiatives which were addressed as strictly water resource issues, namely-the Johnston Negotiations of the mid-1950s, attempts at "water-for-peace" through nuclear desalination in the late 1960s, negotiations over the Yarmuk River in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Global Water Summit Initiative of 1991, all failed to one degree or another, because they were handled separately from overall political discussions. The resolution of water resources issues then had to await the Arab-Israeli peace talks to meet with any tangible progress.

Attempts at Conflict Management

Johnston’s initial proposals were based on a study carried out by Charles Main and the Tennessee Valley Authority at the request of UNRWA to develop the area's water resources and to provide for refugee resettlement. The TVA addressed the problem with a regional approach, pointedly ignoring political boundaries in their study. In the words of the introduction, "the report describes the elements of an efficient arrangement of water supply within the watershed of the Jordan River System. It does not consider political factors or attempt to set this system into the national boundaries now prevailing." The major features of the Main Plan included small dams on the Hasbani, Dan, and Banias, a medium size (175 MCM storage) dam at Maqarin, additional storage at the Sea of Galilee, and gravity flow canals down both sides of the Jordan Valley. Preliminary allocations gave Israel 394 MCM/yr, Jordan 774 MCM/yr, and Syria 45 MCM/yr. (see Table 1). In addition, the Main Plan described only in-basin use of the Jordan River water, although it conceded that "it is recognized that each of these countries may have different ideas about the specific areas within their boundaries to which these waters might be directed"; and excluded the Litani River. Israel responded to the "Main Plan" with the "Cotton Plan," which it allocated Israel 1290 MCM/yr, including 400 MCM/yr from the Litani, Jordan 575 MCM/yr, Syria 30 MCM/yr, and Lebanon 450 MCM/yr. In contrast to the Main Plan, the Cotton Plan called for out-of-basin transfers to the coastal plain and the Negev; included the Litani River; and recommended the Sea of Galilee as the main storage facility, thereby diluting its salinity. In 1954, representatives from Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt established the Arab League Technical Committee under Egyptian leadership and formulated the "Arab Plan." Its principal difference from the Johnston Plan was in the water allocated to each state. Israel was to receive 182 MCM/yr, Jordan 698 MCM/yr, Syria 132 MCM/yr, and Lebanon 35 MCM/yr, in addition to keeping all of the Litani. The Arab Plan reaffirmed in-basin use; excluded the Litani; and rejected storage in the Galilee, which lies wholly in Israel. Johnston worked until the end of 1955 to reconcile U.S., Arab, and Israeli proposals in a Unified Plan amenable to all of the states involved. His dealings were bolstered by a U.S. offer to fund two-thirds of the development costs. His plan addressed the objections of both sides, and accomplished no small degree of compromise, although his neglect of groundwater issues would later prove an important oversight. Though they had not met face to face for these negotiations, all states agreed on the need for a regional approach. Israel gave up on integration of the Litani and the Arabs agreed to allow out-of-basin transfer. The Arabs objected, but finally agreed, to international supervision of withdrawals and construction. Allocations under the Unified Plan, later known as the Johnston Plan, included 400 MCM/yr to Israel, 720 MCM/yr to Jordan, 132 MCM/yr to Syria and 35 MCM/yr to Lebanon (Table 1). Although the agreement was never ratified, both sides have generally adhered to the technical details and allocations, even while proceeding with unilateral development. Agreement was encouraged by the United States, which promised funding for future water development projects only as long as the Johnston Plans allocations were adhered to. Since that time to the present, Israeli and Jordanian water officials have met several times a year, as often as every two weeks during the critical summer months, at so-called "Picnic Table Talks" at the confluence of the Jordan and Yarmuk Rivers to discuss flow rates and allocations.

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:Jordan River: Lessons learned and creative outcomes

Contributed by: Aaron T. Wolf, Joshua T. Newton, Matthew Pritchard (last edit: 12 February 2013)

- ^ Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) (2012). Oregon State University. Available on-line at: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu