Integrated Joint Management Agreements of Mekong River Basin Riparians

| Geolocation: | 18° 17' 47.094", 103° 56' 0.9352" |

|---|---|

| Total Watershed Population: | 72 million |

| Total Watershed Area: | 787,800 km2304,169.58 mi² |

| Climate Descriptors: | Moist tropical (Köppen A-type), Humid mid-latitude (Köppen C-type), Moist, Monsoon |

| Predominant Land Use Descriptors: | agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, forest land |

| Important Uses of Water: | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Fisheries - wild, Fisheries - farmed, Hydropower Generation |

| Water Features: | Mekong River |

| Water Projects: | Mekong Committee, Mekong Commission |

| Agreements: | Statute of the Committee for Co-ordination of Invetiations of Lower Mekong Basin, Agreement on the cooperation for the sustainable development of the Mekong River Basin |

Contents

Summary

The Mekong River flows from the Tibetan Plateau in southwestern China, through the countries of Myanmar, Lao PDR, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, before discharging into the South China Sea. Its mean annual discharge of 475 km3 is the sixth largest of all rivers in the world while it is tenth longest and ranks 21st in terms of drainage area (Costa-Cabral et al., 2008). It is home to 72 million people and its fishery, agricultural and energy resources sustain many more people outside of the basin’s topographic boundaries in southern China and Southeast Asia. Up until recently, the river basin had one of the lowest degrees of streamflow regulation of any major river basin in the world (Nilsson et al., 2005). In 2009, the total active reservoir storage in the basin (8.6 km3) amounted to less than two percent of its mean annual runoff (Kummu et al., 2010). However, the growing energy demand in both China and Southeast Asia has triggered a hydroelectric dam construction boom, which has been projected to increase the active reservoir storage capacity (~90 km3) in the basin to nearly 20 percent of the basin’s mean annual discharge.

Proposed hydropower developments in the Mekong basin have been incredibly contentious. The only multilateral organization with a mandate to regulate hydropower development in the basin is the Mekong River Commission (MRC), which was formed in 1995 after the four lower riparians – Lao PDR, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam – signed the Mekong Agreement to regulate numerous transboundary water management issues, including the construction of hydropower dams. In contrast, the two upstream riparians, China and Myanmar, merely participate in some discussions as designated dialogue partners but are not subject to the Mekong Agreement. China is expected to complete its sixth dam on the Mekong mainstream in 2014 and has planned as many as 23 more (Räsänen et al., 2012).

The Mekong Agreement establishes guidelines for creating regulations to ensure that water resources development does not reduce dry season flows or increase wet season flows in the mainstream of the Mekong, although no specific flow regulations have been established to date. The agreement does not even address the hazards that increased streamflow regulation from reservoir storage for hydroelectric production pose to ecosystems and human livelihoods dependent on the natural flow regime. This article reviews projected and observed hydrologic alteration from hydropower development in four regions of the basin: the Chinese mainstream (a.k.a. Lancang Jiang Cascade), the Lower Mekong basin mainstream, tributaries located wholly within individual Lower Mekong basin countries and the transnational 3S tributary basin shared among Lao PDR, Cambodia and Vietnam.

While much of the scholarly dialogue about the impacts of dams in the Mekong basin has focused on the relations between countries, an increasing body of research documents the inter-sectoral tensions that arise from these developments (Ringler, 2001). Notably, government and industry elite in favor of large hydropower dam construction are often at odds with artisanal fishermen and flood-recession farmers that rely upon the natural flow regime of the river to sustain their livelihoods (Kuenzer et al., 2012). Challenges and possible solutions for transnational and inter-sectoral coordination of hydropower development in the Mekong basin are presented, ranging from basin-scales analyses to project-scale case studies that are relevant for other locations in the basin.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

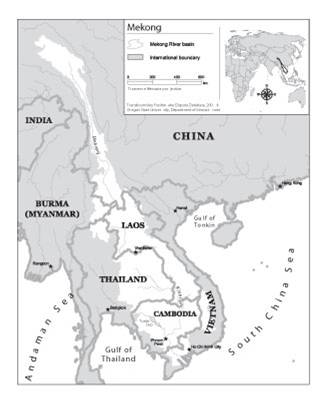

Figure 1. Map of the Mekong River Basin [1]

Figure 1. Map of the Mekong River Basin [1]

Background

Most of the Mekong basin has a humid climate featuring a wet summer and dry winter. The combination of high annual precipitation and mountainous topography endow it with many excellent hydropower production sites, especially in the Yunnan province of southern China, the mainstream of the river in Laos, Thailand and Cambodia, as well as its many left-bank tributaries in Lao PDR, eastern Cambodia and south-central Vietnam. (See Costa-Cabral et al., 2008 for a good introduction to the physical geography of the basin.) However, storage reservoirs are necessary for large tributary hydropower projects due to the extreme seasonality of rainfall in the basin. Hydropower development projects were considered during the period of French colonization in Lao PDR, Cambodia and Vietnam (Wyatt and Baird, 2007). Small hydropower projects (< 10 MW) were constructed in the 1960’s and the first large-scale project, the Nam Ngum Dam in Lao PDR, was commissioned in 1972 to provide electricity for both Thailand and Lao PDR. However, instability from the Second Indochina War (commonly called the Vietnam War in the U.S.) thwarted the foreign investment needed to finance large hydropower projects. Moreover, many high-quality dam sites were situated in areas in which heavy warfare took place in Lao PDR and Vietnam. As the conflicts waned, interest in investment from the West re-emerged until the Asian financial crisis of 1997 stymied numerous burgeoning projects. As the economies recovered, a new wave of investment materialized in the Lower Mekong basin – this time mainly from East Asian countries. Meanwhile, China embarked upon an ambitious hydropower development campaign on the Lancang Jiang beginning with the construction of Manwan Dam in 1993.

Overall, the locations in the basin in which hydropower dams have been constructed and proposed can be coarsely split into four regions: (i) upstream portion of the main stem in China, (ii) downstream portion of the main in the Lower Mekong basin countries, (iii) the tri-national left-bank “3S” tributary basin in southern Lao PDR, eastern Cambodia and south-central Vietnam, and (iv) tributary basins located wholly within riparian countries. The Mekong River Commission has developed the Lower Mekong Hydropower Database to track constructed and proposed projects in the territory of its members while the Chinese government does not maintain a similar database that is publicly available. Räsänen et al. (2012) report that there are 36 operating hydropower dams in the Lower Mekong basin and that there will be dams on the Lancang Jiang once the Nuozhadu Dam is complete in 2014 (HydroChina, 2010; Grumbine and Xu, 2011). They add that the MRC expects that there may be as many as 90 dams in 2022 and 136 in 2060 while another 23 are in various stages of planning in China.

The Problem

As is common in international river basins, integrated planning for efficient watershed management is hampered by the difficulties of coordinating between riparian states with diverse and often conflicting needs. The Mekong, however, is noted mostly for the exceptions as compared with other basins, rather than the similarities. The Mekong, for example, is not an exotic stream, and consequently does not have the sharp management conflicts between well-watered upstream riparians and their water-poor downstream neighbors as, for instance, the Euphrates and the Nile. Historically, the two uppermost riparians, China and Myanmar, have not been participants in basin planning, and they have had no development plans which would disrupt the downstream riparians until very recently. Also, because the region is so well-watered, allocations per se are not been a major issue. Finally, negotiations for joint management of the Mekong were not set off by a flashpoint, as were all of the other examples presented in this work, but rather by creativity and foresight on the part of an authoritative third party - the United Nations - with the willing participation of the lower riparian states.

More recently, however, the liberalization of China’s economy, population growth, demand for increased agriculture yields, growing household demand of water for consumption and sanitation, and shortages of electricity has incited Chinese officials to look to the potential of the Mekong's Upper Basin. It is not, therefore, surprising that China would like to fully develop the Upper Mekong Basin and has proposed the building of 15 dams for hydroelectric power.[2] This unilateral development project alone would have large implications for the downstream riparian states. In the absence of basin-wide consensus and cooperation, these unilateral developments have the potential to make the hydropolitics in the Mekong basin much more contentious.[2] The completion of two major dams on the Chinese part of the Lacang-Mekong mainstream, and the prospect of six or seven more hydropower dams in that area, coupled with the recent in navigability along the Mekong (by blasting the rapids and rocks) underline the urgent need to build and appropriate legal framework and to formulate technical guidelines conducive to turning these potential conflicts into opportunities for sharing benefits.

Attempts at Conflict Management

As noted, the 1957 ECAFE study was met with enthusiasm by the lower Mekong riparians. In mid-September 1957, after ECAFE's legal experts had designed a draft charter for a "Coordination Committee," the lower riparians convened again in Bangkok as a "Preparatory Commission." The Commission studied, modified, and finally endorsed a statute, which legally established the Committee for Coordination of Investigations of the Lower Mekong (Mekong Committee), made up of representatives of the four lower riparians, with input and support from the United Nations. The statute was signed on September 17, 1957.

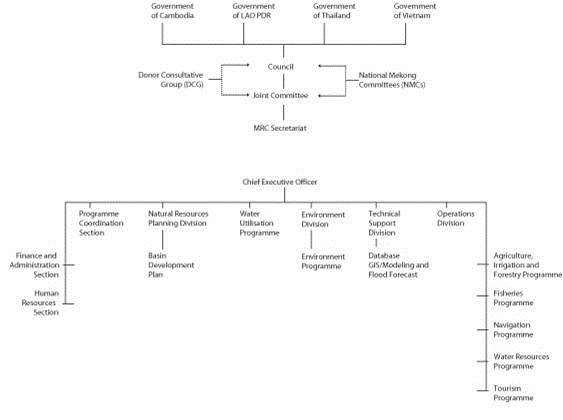

The Committee was composed of "plenipotentiary" representatives of the four countries, meaning that each representative had the authority to speak for their country. The Committee was authorized to, "promote, coordinate, supervise, and control the planning and investigation of water resources development projects in the Lower Mekong Basin." The statute included authority to prepare and submit to participating governments plans for carrying out coordinated research, study, and investigation; make requests on behalf of the participating governments for special financial and technical assistance and receive and administer separately such financial and technical assistance as may be offered under the technical assistance program of the United Nations, the specialized agencies, and friendly governments; draw up and recommend to participating governments criteria for the use of the water of the main river for the purpose of water resources development. It was determined that all meetings must be attended by a representative from each of the four countries, and each decision must be unanimous. Meetings would be held three to four times a year, and chairmanship would rotate annually in alphabetical order by country (Figure 2).

The first Committee session was on October 31, 1957, as was the first donation from the international community-60 million francs (about US$120,000) from France. In late 1957, the Committee, recognizing that data collection was a crucial prerequisite to comprehensive watershed development, asked the UN Technical Assistance Administration to organize a high-level study of the basin. Before the year was out, a mission headed by Lt. General Raymond Wheeler, who had been the deputy commander of the Allied bases in the region during World War II, and later Chief of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, arrived in Bangkok.

The principal recommendation of the Wheeler Mission was that, while reaffirming the great potential of water resources development, suggesting that, properly developed, the river, "could easily rank with Southeast Asia’s greatest natural resources," the absence of data required that a series of detailed hydrographic studies precede any construction. The mission recommended a five-year program of study, to cost approximately $9 million (Table 1).

Figure 2. Organization chart of the Mekong Committee.[1]

Figure 2. Organization chart of the Mekong Committee.[1]

Outcome

The early years were the most productive for the Mekong Committee. Networks of hydrologic and meteorological stations have been established and continued to function despite hostilities in the region, as have programs for aerial mapping, surveying, and leveling. Navigation has been improved along the main stem of the river, but no major project has yet to be initiated, although dozens have been proposed.

The work of the Committee has also helped overcome political suspicion through increased integration. In 1965, Thailand and Laos signed an agreement on developing the power potential of the Nam Ngum River, a Mekong tributary inside Laos. Since most of the power demand was in Thailand, which was willing to buy power at a price based on savings in fuel costs, and since Laos did not have the resources to finance the project, an international effort was mobilized through the Committee to help develop the project. As a sign of the Committee's viability, the mutual flow of electricity for foreign capital between Laos and Thailand was never interrupted, despite hostilities between the two countries.

By the 1970s, the early momentum of the Mekong Committee began to subside, for several reasons. First, the political and financial obstacles necessary to move from data gathering and feasibility studies to concrete development projects have often been too great to overcome. A 1970 Indicative Basin Plan marked the potential shift between planning and large-scale implementation, including immense power, flood control, irrigation, and navigation projects, and setting out a basin development framework for the following thirty years. In 1975, the riparians set out to refine the Committee's objectives and principles for development in support of the Plan in a "Joint Declaration on Principles," including the first (and so far only) precise definition of "reasonable and equitable use" based on the 1966 Helsinki Rules ever used in an international agreement.[3] The plan, which included three of the largest hydroelectric power projects in the world as part of a series of seven cascading dams, was received with skepticism by some in the international community [4] . At the current time, while many projects have been built along the tributaries of the Mekong within single countries, and despite the update of the Indicative Plan in 1987 and a subsequent "Action Plan" which includes only two low dams, no single structure has been built across the main stem.

Second, while the Committee continued to meet despite political tensions, and even despite outright hostilities, political obstacles did take their toll on the their work. Notably, the Committee became a three-member "Interim Committee" in 1978 with the lack of a representative government in Cambodia. Cambodia rejoined the committee as a full participant in 1991, although the Committee still retains "interim" status. Likewise, funding and involvement from the United States, which had been about 12% of total aid to the Committee, was cut off in June 1975, and has not been restored to significant levels.

At its second session, from 10-12 February 1958, the Mekong Committee adopted Wheeler's program as its own five-year plan. It also accepted another suggestion of the Wheeler Mission, that a permanent advisory board of professional engineers "of worldwide reputation" be established. It likewise noted the desirability of having a full-time director with ancillary staff. ECAFE responded and appointed members to the advisory board, secured Committee approval for the appointment of Dr. C. Hart Schaaf as Executive Agent, who assumed office in mid-1959, and established the Committee Secretariat as an ECAFE adjunct body to which UN staff members could be assigned.

With rapid agreement between the riparians came extensive international support for the work of the Committee-by 1961, the Committee's resources came to $14 million, more than enough to fund field surveys which had been agreed to as priority projects. By the end of 1965, twenty countries, eleven international agencies, and several private organizations had pledged a total of more than $100 million. The Secretariat itself was funded by a special $2.5 million grant made by UNDP. This group of international participants has been dubbed "the Mekong club," which has infused the international community with "the Mekong spirit" (Table 2).

Along with the collection of physical data and the establishment of hydrographic networks, the Mekong Committee early encouraged the undertaking of economic and social studies and the initiation of training programs. In 1961, Prof. Gilbert White headed a mission, sponsored by the Ford Foundation, which found that, while existing and planned projects would provide water for irrigation and power for industry, these resources could be used to their maximum benefit only with extensive training of the local population. In an important shift from a strictly engineering approach, many of the mission's recommendations have been adopted.

Table 1. Recommendations of the Wheeler Mission, 1958

| Study or Action | Countries/Agencies Participating | Began |

|---|---|---|

| Preliminary Reconnaissance of Major Tributaries | Japan | 1959 |

| Hydrologic and Meteorological Observations | US, France, Great Britain, India | 1959 |

| Aerial Mapping and Leveling | Canada, Philippines | 1959 |

| Soil Surveys | France | 1959 |

| Geological Investigations | Australia | 1961 |

| Hydrographic Survey | UN, US, France, Private Agencies, Nordic Countries | 1962 |

| Related and Special Studies1 | US, Japan, India, Australia, France | 1959 |

| Preliminary Planning of Projects on Main Stem | US, Japan, India, Australia, France | 1959 |

| Preparation of Basin-Wide Plan | Mekong Committee, aided by ECAFE Secretariat | 1959 |

| Appointment of Advisory Board | 1958 |

1. Including studies of fisheries, agriculture, forestry, minerals, transportation, and power markets.

Finally, some regional politics between the riparians have been played out through the Mekong Committee. Thailand, with the strongest economy and greatest resource needs, has been pushing in recent years for revisions in the Committee's rules which currently allow an effective veto of Thai projects by downstream riparians. Thailand has found its own funding for four Mekong projects within its own territory, and has plans for several more, some of which would probably be opposed by downstream riparians if they were brought before the Mekong Committee. In 1992, Thailand canceled a plenary meeting two days before it was scheduled, and later asked the UNDP to remove the Executive Agent, a request to which the UNDP complied.

Renewed activity came with the signing of the Paris Peace Agreement in 1991, after which Cambodia requested the reactivation of the Mekong Committee. The four lower riparians took up the call and spent the next four years determining a future direction for Mekong activities. The results of these meetings culminated finally in a new agreement, was signed in April 1995, and in which the Mekong Committee became the Mekong Commission. While it is too early yet to evaluate this renewed body, the fact that the riparians have made a new commitment to jointly manage the lower basin speaks well at least for the resiliency of agreements put into place in advance of hot conflict. It should also be noted that Myanmar and China are still not party to the agreement, effectively precluding integrated basin management.

While the establishment of the Mekong Committee and its work provide an impressive example of the potential of integrated watershed management on an international scale, its actual accomplishments have not kept pace with its early momentum, likewise providing lessons for the international arena. The 1995 Agreement Towards Sustainable Development under the Mekong River Commission lacks the political power and support from China and Myanmar needed to successfully implement all of the goals of the Commission and may mirror past momentum if these two countries are not brought on board.

Since its inception in 1995, the Mekong River Commission has been implementing many programs under its jurisdiction. The following are the programs already underway (Mekong River Commission): Basin Development Plan; Water Utilization Program; Environment Program; Flood Management Program; Capacity-Building Program; Agriculture, Irrigation and Forestry Program; Fisheries Program; Navigation Program; and Water Resources and Hydrology. Of the few projects that have been implemented within the Mekong River Commission, none have been constructed on the main stem of the river. Two major dams can be found on tributaries of the Mekong: the Pak Moon dam in Thailand, which is found on the Pak Moon River, and the Theun-Hinboun dam on the Theun River in Laos.

Issues and Stakeholders

NSPD: Ecosystems, Governance, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Development/humanitarian interest, Environmental interest, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens

The Mekong Committee was established in 1957, and then became the Interim Committee in 1978 with original members, except for Cambodia. Early momentum dropped off, but has resurfaced with extensive programs and project proposals-extensive data networks and databases established, Committee re-ratified as Mekong Commission in 1995.

Stakeholders: Countries and Multilateral Organizations:

- Cambodia

- Laos

- Thailand

- Vietnam

- China

- Myanmar

- Mekong Commission

- United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (ECAFE)

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sections are protected, so that each person who creates a section retains authorship and control of their own content. You may add your own ASI contribution from the case study edit tab.

Learn morenone

Key Questions

What role(s) can hydropower play in a nation's energy strategy?

Emphasizing data collection in advance of any construction projects, one both sets the hydrographic stage for more efficient planning, and also may establish a pattern of cooperation through relatively emotion-free issues. The insistence of the Wheeler Mission that extensive data-gathering precede any construction made both management and political sense.

{{{Key Question Description}}}

{{{Key Question Description}}}

{{{Key Question Description}}}

Emphasizing data collection in advance of any construction projects, one both sets the hydrographic stage for more efficient planning, and also may establish a pattern of cooperation through relatively emotion-free issues. The insistence of the Wheeler Mission that extensive data-gathering precede any construction made both management and political sense.

{{{Key Question Description}}}

The greater the international involvement in conflict resolution, the greater the political and financial incentives to cooperate. The pace of development and cooperation in the Mekong River watershed over the years has been commensurate with the level of involvement of the international community. Early accomplishments were impressive, impelled in part by strong UN support and a "Mekong Spirit" on the part of the "Mekong Club" of donors. By the 1970s, the pace of cooperative development began to slacken, partly the result of decreasing involvement by an international community daunted by political obstacles and the size of planned projects.

External Links

- Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) (2012). Oregon State University. — The Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) is a database intended for use in aiding the process of water conflict prevention and resolution. We have developed this database, a project of the Oregon State University Department of Geo-sciences, in collaboration with the Northwest Alliance for Computational Science and Engineering.

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Mekong_New.htm .

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Elhance, A. P. (1999). Hydropolitics in the 3rd World, Conflict and Cooperation in International River Basins. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace.

- ^ International Law Association. (1966). Helsinki rules on the uses of the waters of international rivers. Report of the Fifty-Second Conference, Helsinki, 14-20 August 1966, (London, 1967), pp. 484-532.

- ^ Kirmani, S. S. (1990). Water, peace and conflict management: the experience of the Indus and Mekong river basins. Water International, 15 (4, December), pp. 200-5.

This is the

This is the