Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (Middle East)

| Geolocation: | 32° 30' 0", 38° 0' 0" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 61.96 million |

| Total Area | 822,786822,786 km² 317,677.675 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type), Arid/desert (Köppen B-type), Dry-summer, Dry-winter |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban, religious/cultural sites |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation |

| Water Features: | Jordan River |

| Water Projects: | Middle East Desalination Research Center |

| Agreements: | Treaty of peace between the state of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan |

Contents

Summary

By 1991, several events combined to shift the emphasis on the potential for 'hydro-conflict' in the Middle East to the potential for "hydro-cooperation." The first event was natural, but limited to the Jordan basin. Three years of below-average rainfall caused a dramatic tightening in the water management practices of each of the riparians- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestinians and Syria -including rationing, cut-backs to agriculture by as much as 30%, and restructuring of water pricing and allocations. Although these steps placed short-term hardships on those affected, they also showed that, for years of normal rainfall, there was still some flexibility in the system. Most water decision-makers agree that these steps, particularly regarding pricing practices and allocations to agriculture, were long overdue.

The next series of events were geo-political, and region-wide, in nature. The Gulf War in 1990 and the collapse of the Soviet Union caused a re-alignment of political alliances in the Mideast, which finally made possible the first public face-to-face peace talks between Arabs and Israelis, in Madrid on October 30, 1991. This breakthrough was followed by an organizational meeting in Moscow in January 1992, which established a multilateral track that would act alongside the bilateral track. The multilateral track focuses collaboration efforts on five regionally relevant subjects, including the Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (MWGWR). The "Core Parties" of this group are Israel, the West Bank/Gaza and Jordan.

In water systems as tightly managed and exploited as those of the Middle East, any future unilateral development is likely to be extremely expensive if based on technology, or dangerously politically volatile if threatening the resources of a neighbor. It has been clear to water managers for years that the most viable options include regional cooperation as a minimum prerequisite.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

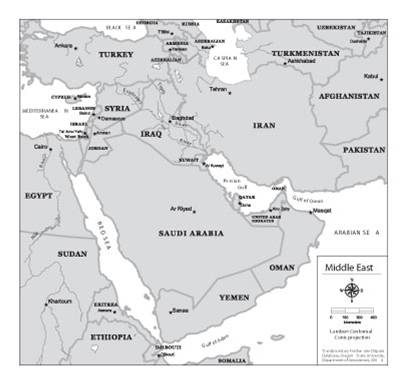

Image 1. Map of all water resources of the Middle East.[1]

Image 1. Map of all water resources of the Middle East.[1]

Background

By 1991, several events combined to shift the emphasis on the potential for 'hydro-conflict' in the Middle East to the potential for "hydro-cooperation." The first event was natural, but limited to the Jordan River basin. Three years of below-average rainfall caused a dramatic tightening in the water management practices of each of the riparians- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestinians and Syria -including rationing, cut-backs to agriculture by as much as 30%, and restructuring of water pricing and allocations. Although these steps placed short-term hardships on those affected, they also showed that, for years of normal rainfall, there was still some flexibility in the system. Most water decision-makers agree that these steps, particularly regarding pricing practices and allocations to agriculture, were long overdue.

The next series of events were geo-political, and region-wide, in nature. The Gulf War in 1990 and the collapse of the Soviet Union caused a re-alignment of political alliances in the Mideast, which finally made possible the first public face-to-face peace talks between Arabs and Israelis, in Madrid on October 30, 1991. This breakthrough was followed by an organizational meeting in Moscow in January 1992, which established a multilateral track that would act alongside the bilateral track. The multilateral track focuses collaboration efforts on five regionally relevant subjects, including the Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (MWGWR). The "Core Parties" of this group are Israel, the West Bank/Gaza and Jordan.

The Problem

Until the current Arab-Israeli peace negotiations began in 1991, attempts at Middle East conflict resolution had either endeavored to tackle political or resource problems, always separately. By separating the two realms of "high" and "low" politics, some have argued, each process was doomed to fail. In water resource issues-the Johnston Negotiations of the mid-1950s, attempts at "water-for-peace" through nuclear desalination in the late 1960s, negotiations over the Yarmouk River in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Global Water Summit Initiative of 1991-all addressed water qua water, separate from the political differences between the parties. All failed to one degree or another.

While political tensions have precluded any comprehensive agreement over the waters of the Middle East, unilateral development in each country has tried to keep pace with the water needs of growing populations and economies. As a result, demand for water resources in most of the countries in the region exceeds at least 90% of the renewable supply, the only exceptions being Lebanon and Turkey . All of the countries and territories riparian to the Jordan River-Israel, Syria, Jordan, and the West Bank-are currently using between 95% and more than 100% of their annual renewable freshwater supply. Gaza exceeds its renewable supplies by 50% every year, resulting in serious saltwater intrusion. In recent dry years, water consumption has routinely exceeded annual supply, the difference usually being made up through overdraft of fragile groundwater systems.

In water systems as tightly managed and exploited as those of the Middle East, any future unilateral development is likely to be extremely expensive if based on technology, or dangerously politically volatile if threatening the resources of a neighbor. It has been clear to water managers for years that the most viable options include regional cooperation as a minimum prerequisite.

Attempts at Conflict Management

Since the opening session of the multilateral talks in Moscow in January 1992, the Working Group on Water Resources, with the United States as "gavel-holder," has been the venue by which problems of water supply, demand and institutions has been raised among the parties to the bilateral talks, with the exception of Lebanon and Syria-Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinians-as well as among the Arab states from the Gulf and the Maghreb. These include Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen . Participating in the talks are also "non-regional delegations," including representatives from governments such as Canada, China, the European Union, Japan, and Turkey, and from donor NGOs, such as the World Bank. The complete list of parties invited to each round includes representatives from Algeria, Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Belgium, Canada, China, Denmark, European Union, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kuwait, Luxembourg, Mauritania, Morocco, Netherlands, Norway, Oman, Palestine, Portugal, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United Nations, United States, the World Bank, and Yemen.

The two tracks of the current negotiations, the bilateral and the multilateral, are explicitly designed not only to close the gap between issues of politics and issues of regional development, but perhaps to use progress in these areas to help catalyze the pace of the other, in a positive feedback loop towards "a just and lasting peace in the Middle East." The idea is that the multilateral working groups would provide forums for relatively free dialogue on the future of the region and, in the process, allow for personal ice-breaking and confidence building to take place. Given the role of the Working Group on Water Resources in this context, the objectives have been more on the order of fact-finding and workshops, rather than tackling the difficult political issues of water rights and allocations, or the development of specific projects. Likewise, decisions are made through consensus only.

The Working Group on Water has met five times (Table 1). The pace of success of each round has vacillated but, in general, has been increasing. The "second" round, the first of the water group alone, has been characterized as "contentious," with initial posturing and venting on all sides. Palestinians and Jordanians, then part of a joint delegation, first raised the issue of water rights, claiming that no progress can be made on any other issue until past grievances are addressed. In sharp contrast, the Israeli position has been that the question of water rights is a bilateral issue, and that the multilateral working group should focus on joint management and development of new resources. Since decisions are made by consensus, little progress was made on either of these issues. Nevertheless, plans were made for continuation of the talks-an achievement in and of itself.

The third round in Washington, DC, in September 1992 made somewhat more progress. Consensus was reached on a general emphasis for the watersheds that the U.S. State Department had proposed in May, focusing on four subjects: enhancement of water data; water management practices; enhancement of water supply, and concepts for regional cooperation and management.

Progress was also made on the definition of the relationship between the multilateral and bilateral tracks. By this third meeting, it became clear that regional water-sharing agreements, or any political agreements surrounding water resources, would not be dealt with in the multilaterals, but that the role of these talks was to deal with non-political issues of mutual concern, thereby strengthening the bilateral track. The goal in the Working Group on Water Resources became to plan for a future region at peace, and to leave the pace of implementation to the bilaterals. This distinction between "planning" and "implementation" became crucial, with progress only being made as the boundary between the two is continuously pushed and blurred by the mediators.

The fourth round in Geneva in April 1993 proved particularly contentious, threatening at points to grind the process to a halt. Initially, the meeting was to be somewhat innocuous. Proposals were made for a series of intersessional activities surrounding the four subjects agreed to at the previous meeting. These activities, including study tours and water-related courses, would help capacity building within while fostering better personal and professional relations.

Table 1. Meetings of the Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources of the Middle East.

| Dates | Location | |

|---|---|---|

| Multilateral organizational meeting 1A | 28-29 January 1992 | Moscow |

| Water Talks, Round 2 | 14-15 May 1992 | Vienna |

| Water Talks, Round 3 | 16-17 September 1992 | Washington, DC |

| Water Talks, Round 4 | 27-29 April 1993 | Geneva |

| Water Talks, Round 5 | 26-28 October 1993 | Beijing |

| Water Talks, Round 6 | 17-19 April 1994 | Muscat |

A After some confusion in numbering, it was eventually officially decided that the multilateral organizational meeting in Moscow represented the first round of the multilateral working groups. Subsequent meetings are therefore numbered correspondingly, beginning with two.

The issue of water rights was raised again, however, with the Palestinians threatening to boycott the intersessional activities. The Jordanians, who had already agreed to discuss water rights with the Israelis in their bilateral negotiations, helped work out a similar arrangement on behalf of the Palestinians. Agreement was not reached at the time, but both sides agreed later after quiet negotiations in May, before the meeting of the working group on refugees in Oslo . The agreement called for three Israeli-Palestinian working groups within the bilateral negotiations, one of which would deal with water rights. The agreement, in which the Palestinians agreed to participate in the intersessional activities, also called for U.S. representatives of the water working group to visit the region. While some may have expected the U.S. representatives to take the opportunity of the visit to take a strong proactive position on the issue of water rights, the delegates adhered to the stance that any specific initiatives would have to come from the parties themselves, and that agreement would have to be by consensus.

By July 1993, the intersessional activities had begun, including approximately 20 activities as diverse as a study tour of the Colorado River basin and a series of seminars on semi-arid lands that focused on capacity building in the region. A series of fourteen courses was designed by the U.S. and the EU for participants from the region, to range in length from two weeks to 12 months, and to cover subjects as broad as concepts of integrated water management and as detailed as groundwater flow modeling.

Following a June 1993 agreement in the multilaterals on a joint US/EC proposal to conduct a regional training needs assessment in the Middle East water sector, a team of specialists developed a Priority Regional Training Action Plan. The plan includes a series of fourteen courses to be offered to managers and professionals from the region over two years commencing in June 1994. The courses were endorsed at the sixth round of water talks in Oman in April 1994. In the end, 20 courses were given to 275 participants from the Middle East . The courses ranged in duration from two weeks to two years (see Sidebar 1).

On 15 September 1993, the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements was signed between Palestinians and Israelis, which defined Palestinian autonomy and the redeployment of Israeli forces out of Gaza and Jericho . Among other issues, the Declaration of Principles called for the creation of a Palestinian Water Administration Authority. Moreover, the first item in Annex III, on cooperation in economic and development programs, included a focus on cooperation in the field of water, including a Water Development Program prepared by experts from both sides, which will also specify the mode of cooperation in the management of water resources in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and will include proposals for studies and plans on water rights of each party, as well as on the equitable utilization of joint water resources for implementation in and beyond the interim period.

Sidebar 1: Regional Training Action Plan

Water sector level courses:

- Concepts of integrated water resources planning and management

- Water resources assessment, planning and management

- Water quality management

- Data collection and management systems

- Alternatives in water resources development

- Principles and applications of international water law

Water sub-sector level courses:

- Management of municipal water supply systems

- Rehabilitation of municipal water supply systems

- Management of wastewater collection and treatment systems

- Development of efficient irrigation systems

Specialized courses:

- Environmental impact assessment techniques

- Groundwater modeling

- Public awareness campaigns for the water sector

- Development, management and delivery of training programs in the water sector

Annex IV describes regional development programs for cooperation, including:

- Development of a joint Israeli-Palestinian-Jordanian Plan for coordinated exploitation of the Dead Sea area;

- The Mediterranean Sea ( Gaza ) - Dead Sea Canal ;

- Regional desalinization and other water development projects;

- Regional plan for agricultural development, including a coordinated regional effort for the prevention of desertification.

The Declaration of Principles also included a description of the mechanisms by which disputes might be resolved. Article XV describes these mechanisms:

- Disputes arising out of the application or interpretation of this Declaration of Principles, or any subsequent agreements pertaining to the interim period, shall be resolved by negotiations through a Joint Liaison Committee to be established.

- Disputes, which cannot be settled by negotiations, may be resolved by a mechanism of conciliation to be agreed upon by the parties.

- The parties may agree to submit to arbitration disputes relating to the interim period, which cannot be settled through conciliation. To this end, upon the agreement of both parties, the parties will establish an Arbitration Committee.

Although the declaration was generally seen as a positive development by most parties, some minor consternation was raised by the Jordanians about the Israeli-Palestinian agreement to investigate a possible Med-Dead Canal . In the working group on regional economic development, the Italians had pledged $2.5 million towards a study of a Red-Dead Canal as a joint Israeli-Jordanian project; building both would be infeasible. The Israelis pointed out in private conversations with the Jordanians that all possible projects should be investigated, and only then could rational decisions on implementation be made.

While a bilateral agreement, the Declaration of Principles helped streamline a logistically awkward aspect of the multilaterals, as the PLO became openly responsible for the talks and the Palestinian delegations separated from the Jordanians. By the fifth round of water talks in Beijing in October 1993, somewhat of a routine seemed to be setting in, whereby reports were presented on each of the four topics agreed to at the second meeting in Vienna-enhancement of data availability; enhancing water supply; water management and conservation; and concepts of regional cooperation and management-and a new series of intercessional activities was announced.

Outcome

By the fifth round of talks in Beijing in October 1993, the following agreements had been reached in each of the four topics.

1. Enhancement of data availability

- Agreement on the need for regional data banks;

- A workshop would be held at USGS facilities in Atlanta as would additional workshops on the subject as part of the US-EU Priority Training Needs Assessment;

- A workshop on the standardization of methodologies and formats for data collection would be held.

2. Enhancing water supply

- Feasibility studies are being conducted on facilities for the desalination of brackish water, by Japan in Jordan and by the EU in Gaza;

- Canada compiled an exhaustive literature review on water technologies;

- Oman 's suggestion was accepted to conduct a survey on the current status of desalination research and technology;

- A Canadian proposal for the installation of a rainwater catchment system in Gaza was accepted, marking the first concrete project to be accepted by the working group

3. Water management and conservation

- Austria ran a seminar on water technologies in arid and semi-arid regions, with special reference to the Middle East;

- The U.S. organized two seminars jointly sponsored by the water and environment working groups, one on the treatment of waste-water in small communities, and one on drylands agriculture;

- The World Bank is carrying out surveys of water conservation in the West Bank, Gaza, and Jordan.

4. Regional cooperation

- The UN is organizing a seminar on various models for regional cooperation and management;

- The U.S. is planning a workshop on weather forecasting;

- Jordan proposed that the working group define a "water charter" for the Middle East, to define the principles of regional cooperation and determine mechanisms for water conflict resolution. The proposal was not adopted.

The sixth round of talks was held in Muscat, Oman in April 1994, the first of the water talks to be held in an Arab country, and the first of any working group to be held in the Gulf. Tensions mounted immediately before the talks as it became clear that the Palestinians would use the occasion as a platform to announce the appointment of a Palestinian National Water Authority. While such an authority was called for in the Declaration of Principles, possible responses to both the unilateral nature and to the appropriateness of the working group as the proper vehicle for the announcement was unclear. Only a flurry of activity prior to the talks guaranteed that the announcement would be welcomed by all parties. This agreement set the stage for a particularly productive meeting. In two days, the working group endorsed:

- An Omani proposal to establish a desalination research and technology center in Muscat, which would support regional cooperation in desalination research among all interested parties. This marked the first Arab proposal to reach consensus in the working group;

- An Israeli proposal to rehabilitate and make more efficient water systems in small-sized communities in the region. This was the first Israeli proposal to be accepted by any working group;

- A German proposal to study the water supply and demand development among interested core parties in the region;

- A U.S. proposal to develop wastewater treatment and re-use facilities for small communities at several sites in the region. The proposal was jointly sponsored by the water and environmental working groups;

- The Regional Water Data Banks Project, a joint venture with the U.S. Geological Survey to create a data sharing systems in the Middle East . This project would initially focus on bring the Palestinian data base up to the speed of Jordan and Israel, so that consistent data would be available to inform and recommend local and regional decision-making.

- Implementation of the US/EU regional training program, as described in the sidebar.

As mentioned above, the working group officially welcomed the announcement of the creation of the Palestinian Water Authority, and pledged to work with the Authority on multilateral water issues.

In 1995, the Core Parties formed the "Executive Action Team" (EXACT), a thus far extremely successful initiative to manage, coordinate and promote project implementation. With the U.S. through the U.S. Geological Survey as gravel holder and executive secretary, it is comprised of two representatives from each Core Party and each Donor Party. Since 1995, EXACT has met biannually to plan, coordinate and direct project implementation. Since its inception, EXACT has met twice a year and focused on implementing 39 recommendations involving the following activities:

- Trainings for water managers and field technicians: database development, interpretation of water quality network data, interpretation of surface-water quality network data, interpretation of surface water network data, and installation and operation of hydro-meteorological and stream gauging stations, statistical analysis and laboratory quality assurance plans (Executive Action Team (EXACT) Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources)

- The establishment of mobile laboratories staffed by trained technicians in the field; 25 regional labs now participate in a semi-annual standard reference sample.

- Joint data base for rainfall data

- Inventory of waste water-related concerns. Water data collection, storage and retrieval systems have been established within the Palestinian Water Authority, and those of the Israeli Hydrological Service and the Jordan Ministry of Water and Irrigation have been improved and enhanced.

The greatest success has been the ongoing communication despite fluctuations in bilateral negotiations.

Progress has been made in bilateral negotiations between Jordan and Israel as well. In September of 1993, the two states agreed to work towards an agenda for peace talks. The sub-agenda for these talks, established on 7 June 1994, included several water-related items, notably in the first heading listed (in advance of security issues, and border and territorial matters), Group A-Water, Energy, and the Environment:

I. Surface water basins.

- A. Negotiation of mutual recognition of the rightful water allocations of the two sides in Jordan River and Yarmouk River waters with mutually acceptable quality.

- B. Restoration of water quality in the Jordan River below Lake Tiberias to reasonably usable standards.

- C. Protection of water quality.

II. Shared groundwater aquifers.

- A. Renewable fresh water aquifers-southern area between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea.

- B. Fossil aquifers-area between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea .

- C. Protection of the water quality of both.

III. Alleviation of water shortage.

- A. Development of water resources.

- B. Municipal water shortages.

- C. Irrigation water shortages.

IV. Potentials of future bilateral cooperation, within a regional context where appropriate.

- [Includes Red Sea-Dead Sea canal; management of water basins; and inter-disciplinary activities in water, environment and energy.]

Following these bilateral talks, the two sides signed the Treaty of Peace Between the State of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in 1994.[2] The parties agreed to recognize the rightful allocations to both of them from the Jordan River, Yarmouk River and the Araba/Arava aquifer. A Joint Water Committee was established comprised of three members from each country that would monitor water use, enforce regulations and develop new cooperation activities.

Talks in 1996 succeeded in creating a number of structures in the areas of data availablility, water management and conservation and regional cooperation and management. Norway agreed to sponsor the establishment of a "Declaration of Principles for Cooperation among Core Parties on Water-Related Matters and New and Additional Water Resources." This declaration made advances in the area of water management by establishing The Waternet Project. The goals of this project are to develop computerized water information systems. A common information system, Waternet Information System (WIS) was inaugurated to assist the Core parties in linking local information networks to a Region computer information network, establish a Regional Waternet and Research Center in Amman Jordan that will maintain this project, stimulate cooperation, and initiate new and joint activities.

The United States agreed to assist the MWGWR in the creation of a Public Awareness and Water Conservation Project, which produced a video and Student Resource Book for youth that highlights the importance of water issues in the region. This group project is done in collaboration with EXACT (Public Awareness and Water Conservation).Luxembourg collaborated with the MWGWR to establish a project on Optimization of Intensive Agriculture under Varying Water Quality Conditions in order to demonstrate how brackish and saline water can be used for sustainable farming in Beit-Hanoun, Gaza. Middle East Desalination Research Center (MEDRC) was established in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman in December of 1996 to conduct, facilitate, promote, coordinate and support basic and applied research in water desalination to reduce the cost of desalination and improve the quality.[3]

Conclusion

Given the length of time that the region has been enmeshed in bitter conflict, the pace of accomplishment of the peace process has been impressive, no less so in the area of water resources. This may be due in part to the structure of the peace talks, with the two complementary and mutually reinforcing tracks-the bilateral and the multilateral. As noted earlier, past attempts at resolving water issues separate from their political framework, dating from the early 1950s through 1991, have all failed to one degree or another. Once the taboo of Israelis and Arabs meeting openly in face-to-face talks was broken in Madrid in October 1991, the floodgates were open, as it were, and a flurry of long-repressed activity on water resources began to take place outside of the official peace process. This included several academic conferences on Middle Eastern water resources in, among other places, Canada, Turkey, Illinois, Washington DC (3) and, notably, the first Israeli-Palestinian conference on water resources in Geneva; unofficial "Track II" dialogues in Nevada, Cairo, and Idaho; the establishment by the IWRA of the "Middle East Water Commission" to help facilitate research on the subject; and organization of the Middle East Water Information Network (MEWIN) to coordinate regional data collection. While this flurry of water-related activity may have been moderately helpful in generating ideas outside of the constraints of the official process, and more so in fostering better personal relations between the water professional of the region, many negotiators involved with the official process suggest limited influence, usually because no mechanism exists to encourage dialogue between the tracks. (The term "Track II" refers to those activities outside of the official negotiations. There may be some confusion, because in the case of the Middle East peace talks, the official process is likewise divided in two-the bilateral negotiations and the multilateral working groups.)

Despite the relative success of the multilateral working group on water, and given its stated objective to deal with non-political issues of mutual concern, one might wonder to where the process might go from here. The working group has performed admirably in the crucial early stages of negotiations as a vehicle for venting past grievances, presenting various views of the future, and, perhaps most important, allowing for personal "de-demonization" and confidence-building on which the future region at peace will be built. Currently, however, there is some frustration on the part of many of the participants that it is not, by design, a vehicle for actually resolving any of the issues at conflict. The contentious topics of water rights and allocations, which some argue must be solved before proceeding with any cooperative projects, are relegated to the bilateral negotiations, where they take a relatively lower priority. Likewise, the principles of integrated watershed management are difficult to encourage: water quantity, quality, and rights all fall within the purview of different negotiating frameworks-the working group on water, the working group on the environment, and the various bilateral negotiations, respectively. There is slightly more overlap than the institutional setting might indicate. Several of the regional delegates sit on both bilateral and multilateral groups, and each of the states have some sort of steering committee, which fosters communication. Furthermore, the U.S. team includes members who participate in both the water and the environment working groups, which helps ensure that issues of water quantity and quality are not entirely separated. Finally, and perhaps somewhat related, are the limitations imposed by Syrian and Lebanese refusal to participate in any of the multilateral working groups. The result of this omission means that a comprehensive settlement of the conflicts related to the Jordan or Yarmouk Rivers are precluded from discussions (see Sidebar 2).

Sidebar 2: Multi-Lateral Working Group A-Water, Energy, and the Environment

Surface Water Basins:

- Negotiation of mutual recognition of the rightful water allocations of the two sides in Jordan River and Yarmouk river waters with mutually acceptable quality.

- Restoration of water quality in the Jordan River below Lake Tiberias to reasonably usable standards.

- Protection of water quality.

Shared Groundwater Aquifers:

- Renewable fresh water aquifers -- southern area between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea.

- Fossil aquifers -- area between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea.

- Protection of the water quality of both.

Alleviation of Water Shortage:

- Development of water resources.

- Municipal water shortages.

- Irrigation water shortages.

Issues and Stakeholders

Help develop capacity for greater efficiency in water supply, demand, and institutions throughout the Middle East, in support of bilateral peace negotiations.

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Governance, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Sovereign state/national/federal government, Local Government, Supranational union, Non-legislative governmental agency, Community or organized citizens, Cultural Interest

Given the length of time that the region has been enmeshed in bitter conflict, the pace of accomplishment of the peace process has been impressive, no less so in the area of water resources. This may be due in part to the structure of the peace talks, with the two complementary and mutually reinforcing tracks-the bilateral and the multilateral.

Stakeholders:

- United States

- United Nations

- European Union

- Canada

- France

- Russia

- Syria

- Lebanon

- Israel

- Jordan

- Palestine

- Egypt

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sections are protected, so that each person who creates a section retains authorship and control of their own content. You may add your own ASI contribution from the case study edit tab.

Learn morenone

Key Questions

Transboundary Water Issues: What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution?

Successful negotiations might include an eventual simultaneous narrowing and broadening of focus, to move from the neutral topics necessary in early stages of negotiation, to dealing with the contentious issues at the heart of a water conflict. Concepts of integrated water management may also be included. While relatively neutral topics were vital in the early stages of the negotiations, some shift may be in order to be able to handle watershed-wide problems such as water rights and allocations. This narrowing of focus might be accompanied by a simultaneous broadening, to include all issues of water rights, quantity and quality relevant to a basin within one framework.

In attempts at resolving particularly contentious disputes, solving problems of politics and resource use is best accomplished in two mutually reinforcing tracks. The most useful lesson of the multilateral working group on water resources is the handling of water and political tensions simultaneously, in the bilateral and multilateral working groups respectively, each track helping to reinforce the other. This lesson has been learned after a long history of failing to solve water problems outside of their political context.

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at:http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Middle_East_New.htm

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at:http://ocid.nacse.org/tfdd/tfdddocs/538ENG.pdf

- ^ Middle East Desalination Research Center (2007). Updated 19 January 2007. Available online at http://www.medrc.org.

| Agreement | Treaty of peace between the state of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan + |

| Area | 822,786 km² (317,677.675 mi²) + |

| Climate | Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type) +, Arid/desert (Köppen B-type) +, Dry-summer + and Dry-winter + |

| Geolocation | 32° 30' 0", 38° 0' 0"Latitude: 32.5 Longitude: 38 + |

| Issue | Help develop capacity for greater efficiency in water supply, demand, and institutions throughout the Middle East, in support of bilateral peace negotiations. + |

| Key Question | What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution? + and To what extent can international actors and movements from civil society influence water management? How and when is this beneficial/detrimental and how can these effects be supported/mitigated? + |

| Land Use | agricultural- cropland and pasture +, industrial use +, urban + and religious/cultural sites + |

| NSPD | Water Quantity +, Water Quality +, Governance + and Values and Norms + |

| Population | 61,960,000 million + |

| Stakeholder Type | Federated state/territorial/provincial government +, Sovereign state/national/federal government +, Local Government +, Supranational union +, Non-legislative governmental agency +, Community or organized citizens + and Cultural Interest + |

| Water Feature | Jordan River + |

| Water Project | Middle East Desalination Research Center + |

| Water Use | Agriculture or Irrigation +, Domestic/Urban Supply + and Hydropower Generation + |

| Has subobjectThis property is a special property in this wiki. | Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (Middle East) + and Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (Middle East) + |

This is the

This is the