Efforts to Resolve the Aral Sea Crisis

| Geolocation: | 45° 1' 39.166", 60° 36' 51.9638" |

|---|---|

| Total Watershed Population: | 46,987,240 million |

| Total Watershed Area: | 1,233,403 km2476,216.898 mi² |

| Climate Descriptors: | Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type), Arid/desert (Köppen B-type), Continental (Köppen D-type), Dry-summer |

| Predominant Land Use Descriptors: | agricultural- cropland and pasture, forest land, rangeland |

| Important Uses of Water: | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply |

| Water Features: | Aral Sea |

| Water Projects: | International Fund for the Aral Sea |

| Agreements: | Nukus Declaration, Agreement on Cooperation in the Management, Utilization and Protection of Interstate Water Resources |

Contents

Summary

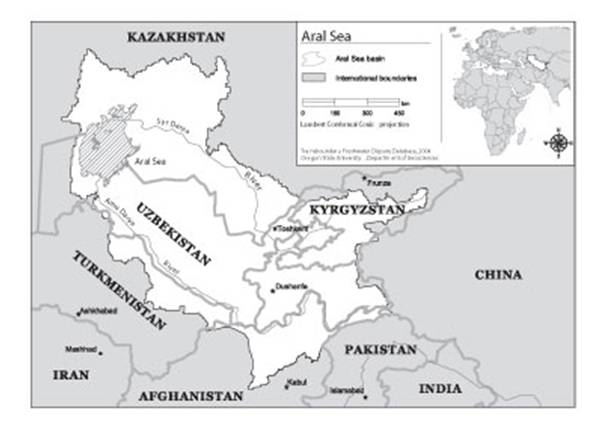

The Aral Sea was, until comparatively recently, the fourth largest inland body of water in the world. Its basin covers 1.8 million km2 , primarily in what used to be the Soviet Union, and what is now the independent republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Small portions of the basin headwaters are also located in Afghanistan, Iran, and China. The major sources of the Sea, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, are fed from glacial meltwater from the high mountain ranges of the Pamir and Tien Shan in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. The environmental problems of the Aral Sea basin are among the worst in the world. Water diversions, agricultural practices, and industrial waste have resulted in a disappearing sea, salinization, and organic and inorganic pollution. The problems of the Aral, which previously had been an internal issue of the Soviet Union, became international problems in 1991. The five new major riparians- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-have been struggling since that time to help stabilize, and eventually to rehabilitate, the watershed. In February 1992, the five republics negotiated an agreement to coordinate policies on their transboundary waters. Subsequent agreements in the 1990s and in 2002 have updated policies and reorganized transboundary water management institutions. As a result the atmosphere gained from the Heads of State of the Aral Sea Basin nations and their recognition that the benefits of cooperation are much higher than that of competition, interstate water management has been coupled with broader economic agreements including trade of hydroelectric energy and fossil fuel to promote regional goals.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

The Problem

The environmental problems of the Aral Sea basin are among the worst in the world. Water diversions, agricultural practices, and industrial waste have resulted in a disappearing sea, salinization, and organic and inorganic pollution. The problems of the Aral, which previously had been an internal issue of the Soviet Union, became international problems in 1991. The five new major riparians- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-have been struggling since that time to help stabilize, and eventually to rehabilitate, the watershed.

Background

The Aral Sea was, until comparatively recently, the fourth largest inland body of water in the world. Its basin covers 1.8 million km2, primarily in what used to be the Soviet Union, and what is now the independent republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Small portions of the basin headwaters are also located in Afghanistan, Iran, and China. The major sources of the Sea, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, are fed from glacial meltwater from the high mountain ranges of the Pamir and Tien Shan in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Irrigation in the fertile lands between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya dates back millennia, although the Sea itself remained in relative equilibrium until the early 1960s. At that time, the central planning authority of the Soviet Union devised the "Aral Sea plan" to transform the region into the cotton belt of the USSR. Vast irrigation projects were undertaken in subsequent years, with irrigated area doubling between 1960 and 1990.[2]

Such intensive cotton monoculture has resulted in extreme environmental degradation. Pesticide use and salinization, along with the region's industrial pollution, have decreased water quality, resulting in high rates of disease and infant mortality. Water diversions, sometimes totaling more than the natural flow of the rivers, have reduced the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya to relative trickles-the Sea itself has lost three-quarters of its volume and half its surface area, and salinity has tripled, all since 1960. The exposed sea beds are thick with salts and agricultural chemical residue, which are carried aloft by the winds as far as the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Attempts at Conflict Management

The intensive problems of the Aral basin were internationalized with the breakup of the Soviet Union. Prior to 1988, both use and conservation of natural resources often fell under the jurisdiction of the same Soviet agency, but each often acted as powerful independent entities. In January 1988, a state committee for the protection of nature was formed, elevated as the Ministry for Natural Resources and Environmental Protection in 1990. The Ministry, in collaboration with the Republics, had authority over all aspects of the environment and the use of natural resources. This centralization came to an end with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Shortly after, the Interstate Coordination Water Commission (ICWC) was formed by the newly independent states to fill the regional planning void that accompanied the loss of Soviet central control.

In February 1992, the five republics negotiated an agreement to coordinate policies on their transboundary waters. Subsequent agreements in the 1990s and in 2002 have updated policies and reorganized transboundary water management institutions.

Outcome

The Agreement on Cooperation in the Management, Utilization and Protection of Interstate Water Resources was signed on February 18, 1992 by representatives from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The agreement calls on the riparians, in general terms, to coordinate efforts to "solve the Aral Sea crisis," including exchanging information, carrying out joint research, and adhering to agreed-to regulations for water use and protection. The agreement also establishes the Interstate Commission for Water Management Coordination to manage, monitor, and facilitate the agreement. Since its inception, the commission has prepared annual plans for water allocations and use, and defined water use limits for each riparian state.

In a parallel development, the Agreement on Joint Actions for Addressing the Problems of the Aral Sea and its Coastal Area, Improving of the Environment and Ensuring the Social and Economic Development of the Aral Sea Region was signed by the same five riparians on March 26, 1993. This agreement also established a coordinating body, the Interstate Council for the Aral Sea (ICAS), which has primary responsibility for "formulating policies and preparing and implementing programs for addressing the crisis." Each State's minister of water management is a member of the council. In order to mobilize and coordinate funding for the Council's activities, the International Fund for the Aral Sea (IFAS) was created.

A long term "Concept" and a short-term "Program" for the Aral Sea was adopted at a meeting of the Heads of Central Asian States in January 1994. The Concept describes a new approach to development of the Aral Sea basin, including a strict policy of water conservation. Allocation of water for preservation of the Aral Sea was recognized as a legitimate water use for the first time. The Program has four major objectives:

- To stabilize the environment of the Aral Sea;

- To rehabilitate the disaster zone around the Sea;

- To improve the management of international waters of the basin; and

- To build the capacity of regional institutions to plan and implement these programs.

These regional activities are supported and supplemented by a variety of governmental and non-governmental agencies, including the European Union, the World Bank, UNEP, and UNDP.

In 1995 the Nukus Declaration was signed by heads of state of the Aral Sea basin nations, and indicated the need for a "unified multi-sectoral approach and the development of cooperation amongst the states and with the international community."[3] Despite this forward momentum, some concerns were raised about the potential effectiveness of these plans and institutions. Some have noted that not all promised funding has been forthcoming. Others (e.g., Dante Caponera 1995) have noted duplication and inconsistencies in the agreements, and warn that they seem to accept the concept of "maximum utilization" of the waters of the basin.[4] Vinogradov (1996) has noted especially the legal problems inherent in these agreements, including some confusion between regulatory and development functions, especially between the commission and the council.[5]

In 1998 the ICAS and IFAS were merged into a reorganized International Fund for the Aral Sea. The principle project goals/components of the IFAS were defined and to be implemented starting in 1998 as follows:

- Component A "Water and Salt Management" prepares the integrated regional water and salt management strategy on the basis of national strategies

- Subcomponent A2 "Water Conservation Competition" disseminates the experience of farms, water users' associations and rayon water management organizations in water conservation

- Component B "Public Awareness" educates the general public to conserve water and to accept burdensome political decisions

- Component C "Dam and Reservoir Management" raises reliability of operation and sustainability of dams

- Component D "Transboundary Water Monitoring" creates the basic physical capacity to monitor transboundary water flows and quality

- Component E "Wetlands Restoration" rehabilitates a wetland area near the Amu Darya delta (Lake Sudoche) and contributes to global biodiversity conservation

Ever since its formation in 1998, IFAS has been under severe constraints and has had difficulties with its credibility and dealing with multi-sectoral issues. The organization was not very successful with its mandate at developing regional water management strategies. Because of this, the board of the IFAS did not meet until 2002, after a three-year hiatus, when it came together to propose a new agenda.[6] Operational agreements and working sessions occurred frequently in the late 1990s among the riparians, and in 2002, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan created the Central Asian Cooperation Organization (CACO) with a broad mandate to promote cooperation among member states on water, energy, and the environment. Up until early 2004, a secretariat still not been established, but one is being planned.

Issues and Stakeholders

The environmental problems of the Aral Sea basin are among the worst in the world.

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Ecosystems, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Local Government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens, Cultural Interest

The Aral Sea was, until comparatively recently, the fourth largest inland body of water in the world. Its basin covers 1.8 million km 2 , primarily in what used to be the Soviet Union, and what is now the independent republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.Water diversions, agricultural practices, and industrial waste have resulted in a disappearing sea, salinization, and organic and inorganic pollution. The problems of the Aral, which previously had been [an] internal issue of the Soviet Union, became international problems in 1991. The five new major riparians- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-have been struggling since that time to help stabilize, and eventually to rehabilitate, the watershed.

Stakeholders:

- Nations: Afghanistan, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

- Other organizations: International Fund for the Aral Sea, Central Asian Cooperation Organization (CACO)

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Invidivuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. Multiple viewpoints may be presented here. ASI sections are protected, so that each person who creates a section retains control of their own content. Please use discussion pages for each ASI for comments and suggestions. You may add your own ASI contribution from the case study edit tab.

Learn more about adding ASIsThere are no ASIs related to this Case Study.

Key Questions

A strong regional economic entity can provide support when issues arise between basin states. The Central Asian Economic Community, now the Central Asian Cooperation Organization, played a key role in mediating between the Aral Sea Basin states when there were difficulties within the International Fund for the Aral Sea. Even though regional economic entities sometimes may be too narrow in their interests, they can provide a stability that basin states may otherwise not have.

Lack of trust and credibility can hinder the process of cooperation. It was apparent during the years of "dormancy" of the International Fund for the Aral Sea that issues of trust and credibility were having a severe effect on the functioning of the organization.

External Links

- Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: Aral Sea — This case was originally incorporated into AquaPedia from the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database organized by Oregon State University. A summary of this case and additional references/resources can be found at this link (Retrieved Jan 7, 2013)

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at:http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Aral_Sea_New.htm

- ^ Aslov, S. M. (2003). IFAS Initiatives in the Aral Sea Basin, 3rd World Water Forum, Kyoto; March 16-23, 2003.

- ^ McKinney, D. C. (1996). Sustainable Water Management in the Aral Sea Basin , Water Resources Update, No. 102, pp. 14-24, 1996.

- ^ Caponera, D. (1987). International Water Resources Law in the Indus Basin. In Water Resources Policy for Asia, ed. M. Ali. Boston: Balkema (4), pp. 509-515.

- ^ Vinogradov, S. (1996). Transboundary Water Resources in the Former Soviet Union: Between Conflict and Cooperation, Natural Resources Journal, Vol 393, pp 406-412.

- ^ McKinney, D. C. (2004). Cooperative management of transboundary water resources in Central Asia. In In the Tracks of Tamerlane-Central Asia's Path into the 21st Century, ed. D. Burghart and T. Sabonis-Helf. Washington DC: National Defense University Press.

| Agreement | Nukus Declaration + and Agreement on Cooperation in the Management, Utilization and Protection of Interstate Water Resources + |

| Area | 1,233,403 km² (476,216.898 mi²) + |

| Climate | Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type) +, Arid/desert (Köppen B-type) +, Continental (Köppen D-type) + and Dry-summer + |

| Geolocation | 45° 1' 39.166", 60° 36' 51.9638"Latitude: 45.0275461 Longitude: 60.6144344 + |

| Issue | The environmental problems of the Aral Sea basin are among the worst in the world. + |

| Key Question | What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution? + and How does asymmetry of power influence water negotiations and how can the negative effects be mitigated? + |

| Land Use | agricultural- cropland and pasture +, forest land + and rangeland + |

| NSPD | Water Quantity +, Water Quality +, Ecosystems + and Governance + |

| Population | 46,987,240 million + |

| Stakeholder Type | Sovereign state/national/federal government +, Local Government +, Non-legislative governmental agency +, Environmental interest +, Community or organized citizens + and Cultural Interest + |

| Water Feature | Aral Sea + |

| Water Project | International Fund for the Aral Sea + |

| Water Use | Agriculture or Irrigation + and Domestic/Urban Supply + |

| Has subobjectThis property is a special property in this wiki. | Efforts to Resolve the Aral Sea Crisis + and Efforts to Resolve the Aral Sea Crisis + |