Flood Management in Maritsa River Basin

| Geolocation: | 41° 40' 11.5769", 26° 31' 8.7109" |

|---|---|

| Total Area | 5260052,600 km² 20,308.86 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Continental (Köppen D-type) |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, conservation lands, industrial use, urban |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation, Industry - non-consumptive use, Other Ecological Services |

Contents

[hide]Summary

Maritsa River (Meriç in Turkish and Evros in Greek) is the longest river that runs solely inside the Balkans. Maritsa River, with its tributaries Arda, Tundza, Ergene and Erythropotamos forms the Maritsa River basin. The basin has three riparians: Bulgaria (upstream), Turkey (downstream) and Greece (downstream). The sole upstream riparian, Bulgaria exploits the hydropower potential of rivers in the basin while downstream countries are devoid of this opportunity because of topographical differences across the basin. Downstream countries mostly rely on basin’s water supply for irrigation and urban/rural drinking water purposes. The basin not only hosts extensive agricultural production, but it is also highly industrialized and densely populated.

The main transboundary problem of the river basin is the recurring flooding of the downstream regions due to extreme precipitation and water released from reservoir dams and hydropower plants in Bulgaria. Usually the city where three branches of the basin join, Edirne, is severely affected by the floods, along with the villages near the Greek-Turkish border which results in high socio-economic cost for the region. Despite repeated flooding incidents in recent years, riparian states Turkey, Bulgaria and Greece couldn’t manage to set up a multilateral transboundary river basin authority to manage and regulate the water flow and maintain flood control. Parties took initial steps towards multilateral cooperation through a European Union project and they set up an early warning system which reduced casualties in recent floods. Yet the mechanism did not contribute to overcoming socio-economic costs associated with flooding.

The challenge is to convince riparian states for a multilateral approach to mitigate the harms caused by flood. Greece and Turkey, downstream countries severely affected by floods must persuade Bulgaria to a more effective and efficient cooperation in transboundary flood management. All tributaries of the river that contribute to flooding of the downstream regions are in Bulgarian segment of the basin, hence early warning and flood prediction systems must be established in Bulgaria, and Bulgarian authorities must share information with the downstream counterparts. Also, topographical constraints of the downstream flat agricultural plains oblige downstream countries to rely on upstream country on building water storage infrastructure. Existing EU water management frameworks may facilitate cooperation between these three countries but current strained relations between Turkey and EU may hamper possible paths to agreements as well.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

Geography

Maritsa river is the longest river running solely in the interior of the Balkans with a total length of 540 km. It originates from Bulgaria and forms the border between Greece and Bulgaria in a small segment, and then between forms Greek-Turkish border in its entirety. After crossing the Greek-Turkish border, one of Maritsa’s main tributaries, Arda, and after crossing the Bulgarian-Turkish border, the other main tributary of Maritsa, Tundza, joins Maritsa near the Turkish city of Edirne. The total catchment of the river basin is approximately 53000km2, shared between three riparians and Bulgaria holds the largest basin area and contributes highest annual discharge. Table in subsection below shows basin area and annual discharge shares of each riparian.

The basin provides suitable conditions for intensive irrigation and livestock raising. Also it hosts industrial clusters. Consequently, the region is highly populated and cities like Plovdiv with a population of 690,000 and Edirne with a population of 400,000 is located in the river basin. Urban inhabitants of these cities rely on the water supply of the river basin for drinking water use.

The segment where Maritsa forms a delta into the Aegean Sea is a wetland of international importance and is protected under Ramsar Convention and EU’s Natura 2000 program for the conservation natural habitats, wild fauna and flora.

| Basin Area (km2) | Annual Discharge (BCM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | 34067 (65%) | 5.7 (71%) |

| Turkey | 14850 (28%) | 1.8 (23%) |

| Greece | 3685 (7%) | 0.5 (6%) |

Source: Kramer, Annika, and Alina Schellig. 2011. “Meric River Basin: Transboundary Water Cooperation at the Border between the EU and Turkey.” In Turkey’s Water Policy, edited by Aysegul Kibaroglu, Waltina Scheumann, and Annika Kramer, 229–49. Springer.

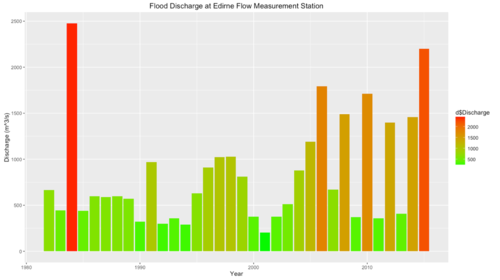

Sources of Conflict

The main problem of the basin is the recurrent flooding of the downstream regions in Greece and Turkey, particularly the city of Edirne located near to the Turkish-Bulgarian border and the agricultural lands in the south of Edirne towards the Evros delta. Downstream regions are intermittently flooded during winter and spring months and the recurrence of flooding increased significantly in the last decade. Maritsa river can flow without flooding with approximately 1600m3/s maximum water recharge in the downstream segment of its basin. Figure 1 shows the maximum levels of discharge measured at Edirne water flow measurement station between 1982-2015. While downstream regions experienced catastrophic flooding in 1984, maximum levels of discharge did not exceed threatening threshold of 1600m3/s until mid-2000s. However, after 2005 and 2006 floods, city of Edirne and agricultural lands around Turkish-Greek border in the downstream segment of the basin experienced recurrent flooding every two years. These instances of flooding cause socio-economic damage to the inhabitants of the region and creates imbalance in the river basin ecosystem. Yet, notwithstanding the increasing intensity of flooding, there has not been significant steps taken towards flood prevention by riparian countries in the last few years.

Main Challenges

Climatic and topographical characteristics of the Maritsa River basin such as high inter-annual variability and heavy soil erosion cause extreme flooding conditions. Also, in the recent years, extreme weather conditions like severe thunderstorms, heavy rainfall, and intensive snowmelt expedited flooding instances in the basin. Despite high variability of weather conditions, upstream and downstream countries do not have a consensus on the causes of increasing extreme flooding in recent years. While the upstream riparian, Bulgaria, puts more emphasis on climate change and extreme weather conditions, downstream riparians point out to the inappropriate management of water reservoir infrastructure in the Bulgarian part of the basin.

Bulgaria as the sole upstream riparian of the basin wants to exploit the hydropower and irrigation potential of the river basin. As the sovereign state controlling the release of water from these reservoirs, Bulgaria has a direct responsibility for managing flooding instances and informing downstream countries about the timing of extreme water discharges. Downstream riparians argue that upstream riparian holds high water levels in hydropower water reservoirs to maximize energy production and to avoid fluctuations in electricity generation. During times of extreme rainfall or snowmelt, this obliges the upstream riparian to flood downstream regions. This can be compensated by building water storage infrastructure in the downstream regions. However, the basin segment at the upper course of the river has predominantly mountainous character while the middle and lower river course is generally composed of flat plain fields. Consequently, topography of the lower segments of the basin is not suitable for storing excessive flooding water. Also, the segment between city of Edirne, the urban center hardest hit by recent floods, and Turkish-Bulgarian border doesn’t have the sufficient land space and topographical characteristics for any flood preventive measure based on water storage infrastructure to be implemented solely on the Turkish side. So, any such infrastructure must be built in cooperation between Bulgaria and other riparian countries. In this regard, cooperation of downstream countries with the upstream riparian is mandatory for multilateral efforts to mitigate flood risks along with flood forecasting, monitoring and establishing early warning systems.

Since initial diplomatic encounters started amongst riparians concerning water use and technical expertise exchange in 1960s, international agreements and technical programs concerning transboundary cooperation has developed on a bilateral basis, despite the need for multilateral cooperation and basin wide management. Besides, over the years, riparians didn’t have an initiative to form a multilateral transboundary river basin authority or a program to address conflicts considering the needs and opinions of different stakeholders in the basin.

Having an EU framework for multilateral cooperation is a crucial component for achieving successful conflict resolution both in terms expertise and financial support. EU projects and funding allowed Turkey and Bulgaria to enact three projects under EU’s PHARE-CBC program, one for data sharing and real-time information exchange and two for flood forecasting and warning between 2006-2010. However, this foundation that could improve cooperation among riparians is currently hindering the progress for multilateral initiatives due to strained relations between EU and Turkey. Turkey is not willing to adopt EU Water Framework Directive and EU Flood Directive due to reservations about transboundary conflicts in Euphrates-Tigris basin. Yet, if Turkey wants to complete negotiations in environment chapter of its EU accession negotiations, it needs to adopt these two pieces of legislation. In return, the EU doesn’t want to channel funds and expertise in transboundary projects in this basin where one of the stakeholders is reluctant in adopting the basic EU legislative framework in the near future.

Bilateral Agreements in Basin

| Countries | Year | Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria - Turkey | 1968 | - Agreement Between the Peoples Republic of Bulgaria and the Republic of Turkey Concerning Co-operation in the Use of the Waters of Rivers Flowing Through the Territory of Both Countries (Maritsa/Marica, Tundzha, Veleka, Rezovska Rivers) |

| 1998 | Agreement Between Bulgaria and Turkey on Cooperation in Energy and Infrastructure Sectors | |

| 2002 | - Agreement on the Approval of the 15th Term Protocol by The Turkish-Bulgarian Joint Committee for Economic and Technical Cooperation |

Way Forward: Applying WDF Approach to Maritsa Basin

Involving Relevant Stakeholders

European Union is in the process of building up a considerable experience in transboundary flood management and it assists member countries for establishing institutional and legal arrangements for cooperation. After the catastrophic flooding in Elbe and Danube River Basins, EU responded with the EU Flood Directive - FD (Directive 2007/60/EC) which required member states to develop flood risk management plans (FRMPs) for flood risk areas. This directive also requires FRMPs to be closely aligned with river basin management plans (RBMPs) conducted under the provisions of EU Water Framework Directive - WFD (Directive 2000/60/EC). Both WDF and FD give prime importance to public participation in environmental planning at the local and state level. In fact, FD’s approach for stakeholder involvement for developing FRMPs is an extension of WDF’s aim to incorporate citizens and citizen groups’ demands while developing RBMPs. These two directives are also complemented by Model Provisions on Transboundary Flood Management under UNECE Helsinki Convention. As EU member states, Greece and Bulgaria submitted their preliminary flood risk plans in 2011 to EU authorities and both countries are in the process of implementing their FRMPs. Turkey as an EU candidate country and a party to UNECE, shares common ground with Bulgaria and Greece about devising a tripartite flood risk plan and FRMP for the Maritsa River Basin. However, until now, neither Greece nor Bulgaria had the motivation to include Turkish state as a governmental stakeholder, or population living in the areas affected by floods as citizen stakeholder participants to the planning and implementation of their respective RBMPs. As a concrete step to adopt good practices of EU transboundary flood management, Turkish government and DSI can initiate processes to evaluate its own river basin plans in the region with the participation of local municipalities (province and district levels), farmers’ organizations in the basin and representatives of the population affected by floods. These processes can include information dissemination components to train stakeholders about the technical details of transboundary flood management. Such initiatives can demonstrate the downstream riparian’s willingness to align itself with EU practices without adopting necessary EU legislation. This can encourage EU Commission to instigate EU member states in the basin to seek ways to start negotiations on a tripartite agreement for preparing a basin-wide flood risk assessment and FRMP with the inclusion of state and local level stakeholders, as well as public representatives, industry delegates (energy generation and hazardous material producing) and farmers to the process. The Elbe River Basin Management Plan which was created with active stakeholder involvement through formal and informal meetings with official authorities international, national and local state level can serve as a source of inspiration for this case.

Joint fact-finding

Since 2002, experts in three riparian countries met in several meetings under bilateral technical projects such as those funded under the PHARE-CBC programme of the EU for flood prevention and early warning systems. As an outcome of these meetings, especially Bulgaria and Turkey took significant steps to improve flood forecasting and early warning infrastructure. Also, EU funds are used for establishing monitoring stations in the basin and integrating data sharing protocols (Kramer and Schellig 2011, 244). In effect, there is sufficient background for cooperation in joint fact-finding at the technical level to achieve basin wide planning for flood monitoring and early warning systems. Nonetheless, the current state of monitoring system is still considered as insufficient for satisfactory flood risk management. Since 2010, EU projects providing financial assistance for infrastructure investments in flood management abruptly ended as an outcome of Turkey’s strained relations with the EU. Three projects between Bulgaria and Turkey envisaged the continuation of collaborative efforts in joint fact-finding at the government experts’ level but this objective never materialized and efforts to improve flood forecasting and early warning systems almost came to a halt. Bulgarian and Turkish experts from DSI and NHMI met almost once every year under different circumstances after 2010 but these meetings were not a part of a long-term basin wide joint fact-finding effort. Nonetheless, EU’s FD still provides a framework that riparians can work through for joint fact-finding and make it more open to the participation of non-technical experts and local stakeholders. In contrast to technocratic paradigm of flood management prioritizing structural protective measures and central government planning, EU’s FD seeks to achieve a Union-wide configuration in flood management regime prioritizing inclusion of civic and private actors and local-level public officials to achieve societal accommodation of risks associated with flooding (Newig et al. 2014). With EU FD’s governance framework, local stakeholders and the public can improve tripartite joint fact-finding efforts by contributing to the process with their anecdotal and local expertise sources to improve expert led analyses for flood management.

Value Creation

Cooperation between Turkey and Bulgaria for infrastructure investments to prevent flooding is underway since mid-1990s. In this matter, the most noteworthy initiative was the Suakacagi Dam located in the Turkish-Bulgaria border, that was planned to be built by both countries. The peculiar aspect of the project is that while the construction of the dam was planned to be on the Turkish side of the border, the majority of the reservoir would collect water on the Bulgarian side. The project is currently suspended as Bulgaria didn’t permit the construction to start and due to international agreements Turkey could not continue the dam construction alone. Also, due to topographical characteristics of the downstream regions, the proposed dam is planned in one of the few locations that is suitable for a reservoir type flood prevention infrastructure to be built on the Turkish side. Another project that had component of mutual value creation was the terminated electricity-for-infrastructure bilateral agreement between Bulgaria and Turkey in 1998. The agreement aimed dams and reservoirs to be built on the Arda river by Turkish private investors and Bulgaria to allow Turkey to purchase electricity produced in these hydropower plants at a discounted price. Both projects were constructive steps for transboundary benefit sharing and value creation, providing benefits for both Bulgaria and Turkey. However, as Kramer and Schellig (2011, 244) argue, these projects were conducted in technocratic fashion rather than with a basin-wide management approach. Hence, value creation must not be confined to setting up reservoirs and dams in the upstream riparian segment of the basin. All three riparians must find solutions to flooding that would benefit local stakeholders in the basin and look beyond simple technical infrastructural solutions for multilateral value creation process. As a proposal, Turkish government can reinvigorate efforts for electricity-for-infrastructure projects and offer Bulgarian side for investing in the local needs of the populations on the Bulgarian side where the hydropower plants would be located. Turkish investors can couple social housing projects, school and hospital buildings and road network infrastructure investments with potential hydropower investments by getting cheap credits from European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and other international development agencies (EBRD). Demands of local stakeholders can be incorporated to the planning of these investments in this manner.

Issues and Stakeholders

Recurring flooding of the downstream regions due to lack of multilateral cooperation for flood risk management. How can downstream countries convince the upstream riparian for cooperation?

NSPD: Water Quantity, Governance, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Local Government, Supranational union, Non-legislative governmental agency, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreNo ASI articles have been added yet for this case

Key Questions

Transboundary Water Issues: What considerations can be given to incorporating collaborative adaptive management (CAM)? What efforts have the parties made to review and adjust a solution or decision over time in light of changing conditions?

Maritsa River is subject to great variations in its flow during flooding season, especially in the last 10-15 years. Flooding monitoring and early warning systems can be beneficial for all riparian states as flooding impacts agricultural and urban areas in all three parts of the basin. Yet, biggest beneficiaries will be downstream countries. There were initiatives funded by the EU in the past few years for technical expertise sharing through Bulgaria-Turkey cross border cooperation projects. Technical experts from DSI (Turkey) and NHMI (Bulgaria) met in several meetings, agreed on basic principles for sharing information and initiated plans to install monitoring stations on the Bulgarian side during 2006-2010 period. Subsequent to the completion of three separate EU projects during this period, Bulgaria started to share river flow and dam capacity data to Turkish government experts. However, fast paced developments for cooperation in the basin stalled after momentum in Turkey’s EU accession process is lost. Following three project conducted with EU cross-border funds, successive projects that were initially planned to complement and improve outcomes of previous projects were not executed. The primary reason is the inadequacy of EU cross-border cooperation funds that are allocated for a transboundary river basin shared with a non-EU country. After 2010, there are sporadic technical committee meetings organized by technical experts from Bulgaria and Turkey without an EU framework solely based on bilateral efforts.

Under the current circumstances, steps to adopt good EU practices for flood prevention in other transboundary and trans-regional water basins of the EU can be taken. With EU’s political encouragement and financial support, a flexible tripartite plan between riparians for managing Maritsa River Basin can be enacted with regard to the EU Water Framework Directive. This plan can adopt good practices of river basin management and flood prevention plans in Elbe River Commission’s Flood Protection Action Plan, Ebro River Basin Plan and Rhine 2020 (for Rhine river basin). Also extending the scope of European Flood Alert System (EFAS) to Maritsa River basin can be suggested by the EU member states Greece and Bulgaria with support of candidate country Turkey. The limiting factor is Turkey’s reluctance to adopt EU WFD before acceding to the EU as a full member state and political hurdles to proceed with Environment Chapter in Turkey’s EU accession negotiations.

Transboundary Water Issues: What kinds of water treaties or agreements between countries can provide sufficient structure and stability to ensure enforceability but also be flexible and adaptable given future uncertainties?

Until this date all agreements between riparians are bilateral and parties did not get involved in an effort to agree on a tripartite treaty or plan to manage and monitor water quantity or quality on Maritsa River basin. Treaties that will include mechanisms to address flood prevention, mitigating flooding risks, setting up early warning systems and concrete rules for data sharing is obligatory. However given the irregularity and unpredictability of the river flows in the basin in the last decade, these mechanisms must not be static and parties must embed follow-up efforts in treaties or agreements to assess the effectiveness of the provisions in the prospective tripartite agreement. First, experts from three riparian states for assessing and resolving technical issues related to flood forecasting, prevention and response must be meet in regular and ad hoc meetings. European Commission technocrats and technical experts from other multiparty European basins authorities facing flooding problems must join these meetings. These meetings must be supported by EU funds under cross-border cooperation programs in order to ensure stability and structure of the agreements. Second, non-governmental and non-technocratic stakeholders from the basin, such as local government representatives of cities with different sizes or farmers unions/cooperatives cultivating lands in the basin must be invited to both intergovernmental and technical meetings. Their inclusion would help decision makers to assess the reliability and effectiveness of any potential tripartite basin-wide flood risk management plans. With including this incentive to evaluate technical decisions with the input of different stakeholders, agreements and treaties retain a certain degree of flexibility and adaptability.

Tagged with: Maritsa Tundja Arda Flooding Flood risk management