Negotiations and Agreements Between Ganges River Basin Riparians

| Geolocation: | 26° 27' 44.2894", 87° 31' 23.9059" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 200200,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 1,634,9001,634,900 km² 631,234.89 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Moist tropical (Köppen A-type), Continental (Köppen D-type), Moist, Monsoon, alpine |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban- high density, religious/cultural sites |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation |

| Water Features: | Ganges River |

| Water Projects: | Mega River Linking Project |

| Agreements: | Treaty Between the government of the Republic of India and the government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh on Sharing of the Ganga/Ganges Waters at Farakka, 1977 Ganges Water Agreement |

Contents

[hide]Summary

While blessed with an abundance of water resources, much of the management problems of the Indian subcontinent come about from the dramatic seasonal variations in rainfall. This management problem is compounded with the creation of new national borders throughout the region. So, too, are the problems which have developed between India and Bangladesh, initially India and Pakistan, over the waters of the Ganges River. The headwaters of the Ganges and its tributaries lie primarily in Nepal and India, where snow and rainfall are heaviest. Flow increases downstream even as annual precipitation drops, as the river flows into Bangladesh, pre-1971 the eastern provinces of the Federation of Pakistan, and on to the Bay of Bengal. The problem over the Ganges is typical of conflicting interests of up- and down-stream riparian’s. India, as the upper riparian, developed plans for water diversions for its own irrigation, navigability, and water supply interests. Initially Pakistan, and later Bangladesh, has interests in protecting the historic flow of the river for its own down-stream uses. The potential clash between up-stream development and down-stream historic use set the stage for attempts at conflict management.A study that simulated water availability under the 1977 and 1996 treaties concluded that a newer treaty is unlikely to make any substantial contribution to alleviate water scarcity during the dry season in southwestern Bangladesh [1]. Besides the issue over low flows to Bangladesh during the dry season has been added that of India's Mega River Linking Project, a plan to link dozens of rivers throughout India by way of aqueducts and pumping stations to transport water from the Ganges River to parts of southern and eastern India that are prone to water scarcity. This project would exacerbate the issue of flows to Bangladesh and has the country very worried. India, acting uni-laterally has up to this point not agreed to speak with Bangladesh regarding the topic [2] .

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

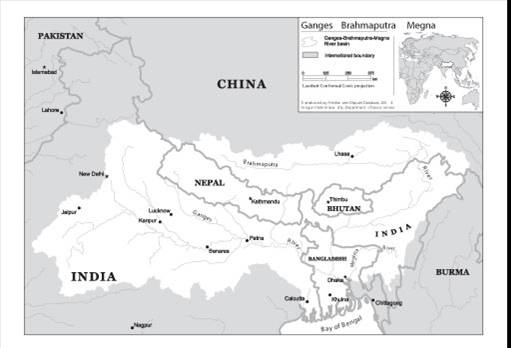

Map of the Ganges- Brahmaputra-Megna basin. [3]

Hydrologic and Geo-political Background

Snow and ice melt from the Himalaya contribute significantly to the Brahmaputra, Ganges and Indus rivers. Water from these trans-boundary Himalayan rivers are subject to disputes between an within countries.

The Ganges sub-basin high population density and related challenges. While the GBM waters in Tibet have important water supply and hydropower potential implications for China; the area, population, and dependence on these waters in South Asia has created more pressing concerns related to cooperative management in the basin.[4]

Precipitation varies from east to west across the basin, and seasonally, with the majority during June - September The South Asian Monsoon and orography of the Himalaya greatly impact the distribution and timing of precipitation in the basin.

In India, the GBM basin accounts for about 60 percent of the total potential flows of all the rivers. The domination of the summer monsoon and non-uniform distribution create more challenges for managing flood risks, and meeting water demand year round. The eastern part of the basin (Meghalaya Hills) averages precipitation of about 11,600 mm per year; but, at the western extremity of the basin, annual precipitation dips as low as 200 millimeters. Irrigation projects received very high priority by India's government; Since independence in 1947, India’s irrigation potential has increased from 20 to 110 million hectares. More recently, a large number of hydro-power projects on the Himalayan rivers have been built (or are planned) on tributaries to meet the power requirements of industry and the growing urban areas. [4]

The Problem

The problem over the Ganges is typical of conflicting interests of up- and down-stream riparians. India, as the upper riparian, developed plans for water diversions for its own irrigation, navigability, and water supply interests. Initially Pakistan, and later Bangladesh, has interests in protecting the historic flow of the river for its own down-stream uses. The potential clash between up-stream development and down-stream historic use set the stage for attempts at conflict management.

Attempts at Conflict Management

The first round of expert-level meetings between India and Pakistan was held in New Delhi from June 28 - July 3, 1960, with three more to follow by 1962. While the meetings were still in progress, India informed Pakistan on January 30, 1961 that construction had begun on the Farakka Barrage. A series of attempts by Pakistan to arrange a meeting at the level of minister was rebuffed with the Indian claim that such a meeting would not be useful, "until full data are available." In 1963, the two sides agreed to have one more expert-level meeting to determine what data was relevant and necessary for the convening of a minister-level meeting. The meeting at which data needs were to be determined, the fifth round at the level of expert, was not held until May 13, 1968. After that meeting, the Pakistanis concluded that agreement on data, and on the conclusions which could be drawn, was not possible, but that enough data was nevertheless available for substantive talks at the level of minister. India agreed only to a series of meetings at the level of secretary, in advance of a minister-level meeting. These meetings, at the level of secretary, commenced on December 9, 1968 and a total of five were held in alternating capitals through July 1970. Throughout these meetings, the different strategies became apparent. As the lower riparian, the Pakistani sense of urgency was greater, and their goal was, "substantive talks on the framework for a settlement for equitable sharing of the Ganges waters between the two countries." India in contrast, whether actually or as a stalling tactic, professed concern at data accuracy and adequacy, arguing that a comprehensive agreement was not possible until the data available was complete and accurate. At the third secretaries' level meeting, Pakistan proposed that an agreement should provide for guarantee to Pakistan of fixed minimum deliveries of the Ganges waters on a monthly basis at an agreed point:

- Construction and maintenance of such works, if any, in India as may be necessary in connection with the construction of the Ganges Barrage in Pakistan ;

- Setting up of a permanent Ganges Commission to implement the agreement;

- Machinery and procedure for settlement of differences and disputes consistent with international usages.

India again argued that such an agreement could only take place after the two sides had agreed to "basic technical facts." The fifth and final secretaries-level meeting was held in New Delhi from July 16-21, 1970, resulting in three recommendations:

- The point of delivery of supplies to Pakistan of such quantum of water as may be agreed upon will be at Farakka

- Constitution of a body consisting of one representative from each of the two countries for ensuring delivery of agreed supplies at Farakka is acceptable in principle

- A meeting would be held in three to six months’ time at a level to be agreed to by the two governments to consider the quantum of water to be supplied to Pakistan at Farakka and other unresolved issues relating thereto and to eastern rivers which have been subject matter of discussions in these series of talks.

Little of practicality came out of these talks, and India completed construction of the Farakka Barrage in 1970. Water was not diverted at the time, though, because the feeder canal to the Bhagirathi-Hooghly system was not yet completed. Bangladesh came into being in 1971, and by March 1972, the governments of India and Bangladesh had agreed to establish the Indo-Bangladesh Joint Rivers Commission, "to develop the waters of the rivers common to the two countries on a cooperative basis." The question of the Ganges, however, was specifically excluded, and would be handled only between the two prime ministers. Leading up to a meeting between prime ministers was a meeting at the level of minister on July 16-17, 1973, where the two sides agreed that a mutually acceptable solution to issues around the Ganges would be reached before operating the Farakka Barrage, and a meeting between foreign ministers on February 13-15, 1974, at which this agreement was confirmed. The prime ministers of India and Bangladesh met in New Delhi on May 12-16, 1974 and, in a declaration on May 16, 1974, they observed that during the periods of minimum flow in the Ganges, there may not be enough water for both an Indian diversion and Bangladeshi needs; agreed that during low flow months, the Ganges would have to be augmented to meet the requirements of the two countries; agreed that determining the optimum method of augmenting Ganges flow should be turned over to the Joint Rivers Commission; and expressed their determination that a mutually acceptable allocation of the water available during the periods of minimum flow in the Ganges would be determined before the Farakka project is commissioned. There were two general approaches to augmenting Ganges flow presented to the Commission, which defined the negotiating stance for years:

- Augmentation through storage facilities within the Ganges basin, proposed by Bangladesh

- Augmentation through diversion of water from the Brahmaputra to the Ganges at Farakka by a link canal, proposed by India.

In a series of five Commission meetings between June 1974 and January 1975, and one minister-level meeting in April 1975, the positions of the two sides coalesced into the following:

Bangladesh Position

- There is adequate storage potential of monsoon flow in the Ganges Basin for Indian needs;

- There is additional storage along the headwaters of the Ganges tributaries in Nepal , and that country might be approached for participation;

- A feeder canal from the Brahmaputra to the Ganges is both unnecessary and would have detrimental effects within Bangladesh , not least of which would be massive population resettlement;

- Indian needs would be better met through amending the pattern of diversion of Ganges water into the Bhagirathi-Hooghly, and constructing a navigation link from Calcutta to the sea via Sunderban.

India Position

- Additional storage possibilities in India are limited, and not sufficient to meet Indian development needs;

- The most viable option both to supplement the low flow of the Ganges, and for regional development, is a link canal and storage facilities on the Brahmaputra, to be developed in stages for mutual benefit;

- Approaching Nepal or other third countries is beyond the scope of the Commission, as is discussing amending the pattern of diversion into the Bhagirathi-Hooghly;

- Constructing a separate navigation canal is not connected to the question of optimum development of water resources in the region.

At a minister-level meeting in Dhaka between April 16-18, 1975, India asked that, while discussions continue, the feeder canal at Farakka be run during that current period of low flow. The two sides agreed to a limited trial operation of the barrage, with discharges varying between 11,000 and 16,000 cusecs in ten-day periods from April 21 to May 31, 1975, with the remainder of the flow guaranteed to reach Bangladesh. Without renewing or negotiating a new agreement with Bangladesh, India continued to divert the Ganges waters at Farakka after the trial run, throughout the 1975-76 dry season, at the full capacity of the diversion-40,000 cusecs. There were serious consequences in Bangladesh resulting from these diversions, including desiccation of tributaries, salination along the coast, and setbacks to agriculture, fisheries, navigation, and industry. Four more meetings were held between the two states between June 1975 and June 1976, with little result. In January 1976, Bangladesh lodged a formal protest against India with the General Assembly of the United Nations which, on November 26, 1976, adopted a consensus statement encouraging the parties to meet urgently at the ministerial level for negotiations, "with a view to arriving at a fair and expeditious settlement." Spurred by international consensus, negotiations re-commenced on December 16, 1976. At an April 18, 1977 meeting, an understanding was reached on fundamental issues, which culminated in the signing of the Ganges Waters Agreement on November 5, 1977.

Outcome

In principle, the Ganges Water Agreement covers:

- Sharing the waters of the Ganges at Farakka.

- Finding a long term solution for augmentation of the dry season flows of the Ganges.

Specific provisions, described as not establishing any general principles of law or precedent, include (paraphrased):

- Art. I. The quantum of waters agreed to be released would be at Farakka.

- Art. II. The dry season availability of the historical flows was established from the recorded flows of the Ganges from 1948 to 1973 on the basis of 75% availabilities. The shares of India and Bangladesh of the Ganges flows at 10-day periods are fixed, the shares in the last 10-day period of April (the leanest) being 20,500 and 34,500 cusec respectively out of 55,000 cusec availability at that period.

- Art. III. Only minimum water would be withdrawn between Farakka and the Bangladesh border.

- Art. IV-VI. Provision was made for a Joint Committee to supervise the sharing of water, provide data to the two governments, and submit an annual report.

- Art. VII. Provisions were made for the process of conflict resolution: The Joint Committee would be responsible for examining any difficulty arising out of the implementation of the arrangements of the Agreement.

- Any dispute not resolved by the Committee would be referred to a panel of an equal number of Indian and Bangladeshi experts nominated by the two governments.

- If the dispute is still not resolved, it would be referred to the two Governments which would, "meet urgently at the appropriate level to resolve it by mutual discussion and failing that by such other arrangements as they may mutually agree upon.

- Art. VIII: The two sides would find out a long-term solution of the problem of augmentation of the dry season flows of the Ganges.

The Agreement would initially cover a period of five years. It could be extended further by mutual agreement. The Joint Rivers Commission was again vested with the task of developing a feasibility study for a long-term solution to the problems of the basin, with both sides re-introducing plans along the lines described above. By the end of the five-year life of the agreement, no solution had been worked out. In the years since, both sides and, more recently, Nepal, have had years of greater and less success at reaching towards agreement. Since the 1977 accord: A joint communiqué was issued in October 1982, in which both sides agreed not to extend the 1977 agreement, but would rather initiate fresh attempts to achieve a solution within 18 months-a task not accomplished. An Indo-Bangladesh Memorandum of Understanding was signed on November 22, 1985, on the sharing of the Ganges dry season flow through 1988, and establishing a Joint Committee of Experts to help resolve development issues. India’s proposals focused on linking the Brahmaputra with the Ganges, while Bangladesh’s centered on a series of dams along the Ganges headwaters in Nepal. Although both the Joint Committee of Experts and the Joint Rivers Commission met regularly throughout 1986, and although Nepal was approached for possible cooperation, the work ended inconclusively. The prime ministers of Bangladesh and India discussed the issue of river water-sharing on the Ganges and other rivers in May, 1992, in New Delhi. Each directed their ministers to renew their efforts to achieve a long-term agreement on the Ganges, with particular attention to low flows during the dry season. Subsequent to that meeting, there has been one minister-level and one secretary-level meeting, at which little progress was reportedly made. Between 1988, when the last agreement lapsed, and 1996, no agreement was in place between India and Bangladesh. During this time, India granted Bangladesh only a portion of the flow of the Ganges, with no minimum flow guaranteed, and no special provisions for drought years. Each side kept roughly to its positions as stated above, with little room for compromise. Regional schemes were proposed, often providing benefits not only to India and Bangladesh, but also to Nepal, landlocked but with tremendous hydro-power potential which might be traded for access to the sea. In December 1996, a new treaty was signed between the two riparians, based generally on the 1985 accord, which delineates a flow regime under varying conditions. The most notable change in the 1996 Ganges River Treaty is the establishment of a new formula for the distribution of Ganges waters from January 1st to May 31st, the region's dry season, at Farraka Barrage. The following schedule is to be respected with regards to 10-day period flows (Table 1).If flows at Farakka Barrage should fall below 50,000 cusecs, the two governments will meet together to consult as to the appropriate actions taking into consideration "principles of equity, fair play and no harm to either party." The two governments are required by the treaty to review the sharing arrangements at five-year intervals. If the parties are not able to come to agreement, India is to release no less than 90 percent of Bangladesh’s flow at Farraka as stated by the above schedule until a solution can mutually agreed upon. While this agreement should help reduce regional tensions, issues such as extreme events and upstream uses are not covered in detail. Notably, Nepal, China, and Bhutan, not party to the treaty, have their own development plans that could impact the agreement. In addition, the treaty does not contain any arbitration clause to ensure that the parties uphold its provision.

Table 1. Ganges River Allocations [3]

| Flow Amount | India | Bangladesh |

|---|---|---|

| <70,000 cusecs | 50% | 50% |

| 70,000-75,000 cusecs | Balance of flow | 35,000 cusecs |

| >75,000 cusecs | 40,000 cusecs | Balance of flow |

The 1996 treaty was based on data about water discharges at the Farakka dam between 1949 and 1988. Since that time, however, increased upstream draws have significantly lowered the discharges and statistical analysis indicates that neither Bangladesh nor India will be able to withdraw their respective allocations [5] . The very first season following signing of the treaty, in April 1997, India and Bangladesh were involved in their first dispute over cross-boundary flow: water passing through the Farakka dam dropped below the minimum provided in the treaty, prompting Bangladesh to request a review of the state of the watershed. A study that simulated water availability under the 1977 and 1996 treaties concluded that the newer treaty is unlikely to make any substantial contribution to alleviate water scarcity during the dry season in southwestern Bangladesh [1].

Besides the issue over low flows to Bangladesh during the dry season has been added that of India's Mega River Linking Project, a plan to link dozens of rivers throughout India by way of aqueducts and pumping stations to transport water from the Ganges River to parts of southern and eastern India that are prone to water scarcity. This project would exacerbate the issue of flows to Bangladesh and has the country very worried. India, acting uni-laterally has up to this point not agreed to speak with Bangladesh regarding the topic [2] .

Issues and Stakeholders

Negotiating an equitable allocation of the flow of the Ganges River and its tributaries between the riparian states; developing a rational plan for integrated watershed development, including supplementing Ganges flow.

NSPD: Water Quantity, Governance, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Local Government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Community or organized citizens

Besides the issue over low flows to Bangladesh during the dry season, India’s new plan, the Mega River Linking Project, a plan to link dozens of rivers throughout India by way of aqueducts and pumping stations to transport water from the Ganges River to parts of southern and eastern India that are prone to water scarcity. This project would exacerbate the issue of flows to Bangladesh and has the country very worried. India, acting uni-laterally has up to this point not agreed to speak with Bangladesh regarding the topic. [2]

Stakeholders:

- China

- Bangladesh

- Bhutan

- India

- Myanmar (Burma)

- Nepal

- United Nations

- Indo-Bangladesh Joint Rivers Commission

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:Ganges Basin: insights from the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database

(last edit: 13 November 2012)

Key Questions

Transboundary Water Issues: What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution?

The answer is twofold:

- Agreeing early on the appropriate diplomatic level for negotiations is an important step in the pre-negotiation phase. Much of the negotiations between India and Pakistan and, later, India and Bangladesh, were spent trying to resolve the question of what was the appropriate diplomatic level for negotiations.

- Short-term agreements which stipulate that the terms are not permanent can be useful steps in long-term solutions. However, a mechanism for continuation of the temporary agreement in the absence of a long-term agreement is crucial. Agreements on the distribution of Ganges waters have been short in duration, providing initial impetus for signing, but providing difficulties when they lapse.

Unequal power relationships, without strong third-party involvement, create strong dis-incentives for cooperation. India, the stronger party both Geo-strategically and Hydro-strategically, has little incentive to reach agreement with Bangladesh. Without strong third-party involvement, such as that of the World Bank between India and Pakistan on the Indus, the dispute has gone on for years.

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Tanzeema, S. and Faisal, I. M. (2001). Sharing the Ganges: a critical analysis of the water sharing treaties. Water Policy, 3 (1), pp. 13-28

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Pearce, F. (2003). Conflict Looms over India’s Colossal River Plan. New Scientist. [online]. Updated 19 January 2007 Available at http:// www.newscientist.com

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Ganges_New.htm

- ^ 4.0 4.1 https://blog.waterdiplomacy.org/2014/03/the-case-for-water-diplomacy-for-south-asia-ganges-brahmaputra-meghna-basin/

- ^ Mirza, M. (2003). The Ganges water-sharing treaty: risk analysis of the negotiated discharge. International Journal of Water, 2 (1), pp. 57-74