Efforts to Resolve the Aral Sea Crisis

| Geolocation: | 45° 1' 39.166", 60° 36' 51.9638" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 46,987,24046,987,240,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 1,233,4031,233,403 km² 476,216.898 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type), Arid/desert (Köppen B-type), Continental (Köppen D-type), Dry-summer |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, forest land, rangeland |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply |

| Water Features: | Aral Sea, Amu Darya (River), Syr Darya (River) |

| Water Projects: | International Fund for the Aral Sea |

| Agreements: | Nukus Declaration, Agreement on Cooperation in the Management, Utilization and Protection of Interstate Water Resources |

Contents

[hide]Summary

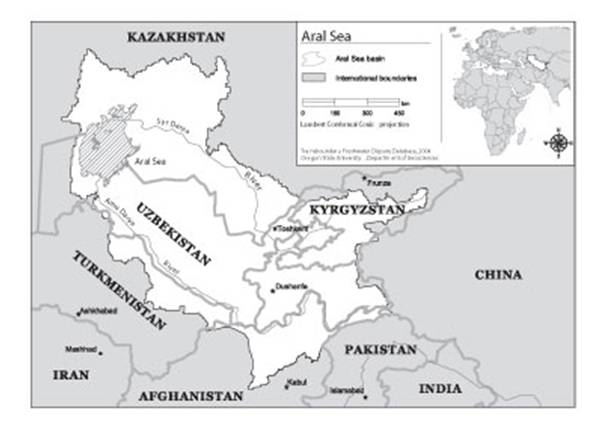

The Aral Sea was, until comparatively recently, the fourth largest inland body of water in the world. Its basin covers 1.8 million km2 , primarily in what used to be the Soviet Union, and what is now the independent republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Small portions of the basin headwaters are also located in Afghanistan, Iran, and China. The major sources of the Sea, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, are fed from glacial meltwater from the high mountain ranges of the Pamir and Tien Shan in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. The environmental problems of the Aral Sea basin are among the worst in the world. Water diversions, agricultural practices, and industrial waste have resulted in a disappearing sea, salinization, and organic and inorganic pollution. The problems of the Aral, which previously had been an internal issue of the Soviet Union, became international problems in 1991. The five new major riparians- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-have been struggling since that time to help stabilize, and eventually to rehabilitate, the watershed. In February 1992, the five republics negotiated an agreement to coordinate policies on their transboundary waters. Subsequent agreements in the 1990s and in 2002 have updated policies and reorganized transboundary water management institutions. As a result the atmosphere gained from the Heads of State of the Aral Sea Basin nations and their recognition that the benefits of cooperation are much higher than that of competition, interstate water management has been coupled with broader economic agreements including trade of hydroelectric energy and fossil fuel to promote regional goals.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

The Problem

The environmental problems of the Aral Sea basin are among the worst in the world. Water diversions, agricultural practices, and industrial waste have resulted in a disappearing sea, salinization, and organic and inorganic pollution. The problems of the Aral, which previously had been an internal issue of the Soviet Union, became international problems in 1991. The five new major riparians- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-have been struggling since that time to help stabilize, and eventually to rehabilitate, the watershed.

Background

The Aral Sea Basin (ASB), a region of about 158.5 million hectares in Central Asia, is home to what was formerly the world’s 4th largest lake, and perhaps one of recent history’s most infamous case studies of international water conflict. The primary sources of water in the region are the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, originating from snowmelt in the Tien Shan and Pamir mountain ranges to the Southeast. These rivers wind through the expanse of desert, plains, and steppes making up the arid landscape of the basin, until they empty into the Aral Sea. The basin and its waters primarily serve five countries, the former Soviet nations of: Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Since Soviet management of the basins began in the 1960’s, water has been diverted from the basin’s rivers at increasingly unsustainable levels. Left poor and disorganized by the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990’s, each of the five newly independent states began diverting yet more water from these rivers to keep their ailing economies afloat. As a result, tensions have risen steadily among the 5 nations over the allocation of the basin’s supply of fresh water, which is declining both in quality and quantity while demand from increasing populations and agricultural sectors grows [2]. The primary agriculture in most countries (with the possible exception of Kazakhstan) is in cash crops, especially cotton, which requires heavy irrigation to be maintained in the arid climate [3]. Water scarcity due to excessive withdrawal and irresponsible water use in the region has led to declines in land productivity of up to 66%, with the value of one hectare of available land falling from $2,000 in the 1980’s to less than $700 in 2003. [4].

The environmental damage inflicted upon the region is especially well illustrated by the Aral Sea itself, which bears the brunt of the damage caused by excessive diversion of the basin’s rivers. Since Soviet agricultural development took off in the 1960’s, the Aral Sea has lost 88% of its area and 92% of its volume, while its surface level has dropped by 26 meters [5]. Erosion, waterlogging, and excessive evaporation due to poor upstream irrigation practices have led to a steady increase in salinity throughout the last 50 years, resulting in a total increase of more than 2,000% [6]. The once booming fishing industry enjoyed by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which at one point yielded more than 44,000 tonnes of fish per year, has disappeared entirely, leading to the loss of more than 10,000 jobs [7]. Every native species of fish was driven to local extinction due to high salinity, and even introduced, highly salt-tolerant species promptly went extinct as salinity continued to rise. More than 50% of all mammal and bird species once supported in the area have been completely extirpated [8].

The ASB’s growing environmental crisis creates a number of pressing health concerns, including high instances of respiratory illness due to toxic dust storms kicked up from the dry bed of the former Sea [9] [10]. Infant mortality in some particularly affected areas is as high as 100/1,000 [11]. As if human health were not enough of a problem, agricultural yields are declining as populations grow and economic dependence on agriculture increases. Crop yields on some agricultural lands have declined by a factor of two or more due to soil salinization, which affects 90% of irrigated land in some parts of the region [12].

Among the myriad factors contributing to this complex and dire water problem, one factor in particular is widely considered the primary driving force behind water scarcity in the ASB: wasteful irrigation practices [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18]. Some authors believe that inefficient use of water may be the cause of artificial scarcity of water in the ASB, and that if water were used more efficiently, especially in farming, the available water would meet the growing countries’ needs [19]. Considering that irrigation accounts for up to 90% of some countries’ water use, any improvement in irrigation practices has the potential to contribute immensely to solving water scarcity and quality problems in the ASB [20].

It is thought that unsustainable irrigation practices started as early as the 1920’s, when, after the Bolshevik revolution, the Soviet Union took command of water resources in Central Asia, enlarging irrigation systems and combining what had otherwise been sustainable farming units into large state-run collective farms called kolkhozy or sovkhozy [21]. The primary focus of the kolkhozy was to increase withdrawal for irrigation from both of the ASB rivers in order to increase production of cotton and rice for the rest of the Union. From the 1960’s to the 1980’s, the area of irrigated land in Central Asia increased by 150% [22]. This dramatic increase in agricultural water use eventually led to the environmental, economic, and political problems reviewed above [23]. Soviet water planners, seeking to continually bring in project funding, started more projects than they could finish, leaving many incomplete, and using poor materials for the construction of irrigation infrastructure while devoting few funds to maintenance [24].

By the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990’s, more than 50% of irrigation and drainage systems (I & D) in most Central Asian countries were dysfunctional or in disrepair [25]. Though Soviet funds and management had scarcely been able to maintain moderately efficient irrigation systems, the situation grew worse as the independent states largely shirked responsibility for operation and maintenance, leaving farmers to fend for themselves. In Kazakhstan, for example, available government funds for operation and management were less than 1/20th of those put forth by the soviet water management authorities [26]. With farm incomes declining to between 7-40% of levels during the Soviet era, farmers lacked the funding and equipment needed to maintain the irrigation and drainage systems upon which they depended [27]. This lack of funding and the vacuum of management left behind by the sudden disappearance of the Soviet authority allowed shoddy irrigation systems to decline further. Overall water conveyance efficiency in Central Asia is estimated at 40-80% [28], while water withdrawals per hectare are nearly 50% higher (i.e., more water is being used or wasted) than in highly inefficient systems in comparably arid climates like Egypt [29].

Attempts at Conflict Management

The intensive problems of the Aral basin were internationalized with the breakup of the Soviet Union. Prior to 1988, both use and conservation of natural resources often fell under the jurisdiction of the same Soviet agency, but each often acted as powerful independent entities. In January 1988, a state committee for the protection of nature was formed, elevated as the Ministry for Natural Resources and Environmental Protection in 1990. The Ministry, in collaboration with the Republics, had authority over all aspects of the environment and the use of natural resources. This centralization came to an end with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Shortly after, the Interstate Coordination Water Commission (ICWC) was formed by the newly independent states to fill the regional planning void that accompanied the loss of Soviet central control.

In February 1992, the five republics negotiated an agreement to coordinate policies on their transboundary waters. Subsequent agreements in the 1990s and in 2002 have updated policies and reorganized transboundary water management institutions.

Outcome

The Agreement on Cooperation in the Management, Utilization and Protection of Interstate Water Resources was signed on February 18, 1992 by representatives from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The agreement calls on the riparians, in general terms, to coordinate efforts to "solve the Aral Sea crisis," including exchanging information, carrying out joint research, and adhering to agreed-to regulations for water use and protection. The agreement also establishes the Interstate Commission for Water Management Coordination to manage, monitor, and facilitate the agreement. Since its inception, the commission has prepared annual plans for water allocations and use, and defined water use limits for each riparian state.

In a parallel development, the Agreement on Joint Actions for Addressing the Problems of the Aral Sea and its Coastal Area, Improving of the Environment and Ensuring the Social and Economic Development of the Aral Sea Region was signed by the same five riparians on March 26, 1993. This agreement also established a coordinating body, the Interstate Council for the Aral Sea (ICAS), which has primary responsibility for "formulating policies and preparing and implementing programs for addressing the crisis." Each State's minister of water management is a member of the council. In order to mobilize and coordinate funding for the Council's activities, the International Fund for the Aral Sea (IFAS) was created.

A long term "Concept" and a short-term "Program" for the Aral Sea was adopted at a meeting of the Heads of Central Asian States in January 1994. The Concept describes a new approach to development of the Aral Sea basin, including a strict policy of water conservation. Allocation of water for preservation of the Aral Sea was recognized as a legitimate water use for the first time. The Program has four major objectives:

- To stabilize the environment of the Aral Sea;

- To rehabilitate the disaster zone around the Sea;

- To improve the management of international waters of the basin; and

- To build the capacity of regional institutions to plan and implement these programs.

These regional activities are supported and supplemented by a variety of governmental and non-governmental agencies, including the European Union, the World Bank, UNEP, and UNDP.

In 1995 the Nukus Declaration was signed by heads of state of the Aral Sea basin nations, and indicated the need for a "unified multi-sectoral approach and the development of cooperation amongst the states and with the international community."[30] Despite this forward momentum, some concerns were raised about the potential effectiveness of these plans and institutions. Some have noted that not all promised funding has been forthcoming. Others (e.g., Dante Caponera 1995) have noted duplication and inconsistencies in the agreements, and warn that they seem to accept the concept of "maximum utilization" of the waters of the basin.[31] Vinogradov (1996) has noted especially the legal problems inherent in these agreements, including some confusion between regulatory and development functions, especially between the commission and the council.[32]

In 1998 the ICAS and IFAS were merged into a reorganized International Fund for the Aral Sea. The principle project goals/components of the IFAS were defined and to be implemented starting in 1998 as follows:

- Component A "Water and Salt Management" prepares the integrated regional water and salt management strategy on the basis of national strategies

- Subcomponent A2 "Water Conservation Competition" disseminates the experience of farms, water users' associations and rayon water management organizations in water conservation

- Component B "Public Awareness" educates the general public to conserve water and to accept burdensome political decisions

- Component C "Dam and Reservoir Management" raises reliability of operation and sustainability of dams

- Component D "Transboundary Water Monitoring" creates the basic physical capacity to monitor transboundary water flows and quality

- Component E "Wetlands Restoration" rehabilitates a wetland area near the Amu Darya delta (Lake Sudoche) and contributes to global biodiversity conservation

Ever since its formation in 1998, IFAS has been under severe constraints and has had difficulties with its credibility and dealing with multi-sectoral issues. The organization was not very successful with its mandate at developing regional water management strategies. Because of this, the board of the IFAS did not meet until 2002, after a three-year hiatus, when it came together to propose a new agenda.[33] Operational agreements and working sessions occurred frequently in the late 1990s among the riparians, and in 2002, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan created the Central Asian Cooperation Organization (CACO) with a broad mandate to promote cooperation among member states on water, energy, and the environment. Up until early 2004, a secretariat still not been established, but one is being planned.

Issues and Stakeholders

The environmental problems of the Aral Sea basin are among the worst in the world.

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Ecosystems, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Local Government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens, Cultural Interest

The Aral Sea was, until comparatively recently, the fourth largest inland body of water in the world. Its basin covers 1.8 million km 2 , primarily in what used to be the Soviet Union, and what is now the independent republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.Water diversions, agricultural practices, and industrial waste have resulted in a disappearing sea, salinization, and organic and inorganic pollution. The problems of the Aral, which previously had been [an] internal issue of the Soviet Union, became international problems in 1991. The five new major riparians- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-have been struggling since that time to help stabilize, and eventually to rehabilitate, the watershed.

Stakeholders:

- Nations: Afghanistan, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

- Other organizations: International Fund for the Aral Sea, Central Asian Cooperation Organization (CACO)

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:The role of economic entities, trust, and credibility in resolving the Aral Sea Crisis

Contributed by: Aaron T. Wolf, Joshua T. Newton, Matthew Pritchard (last edit: 12 February 2013)

Key Questions

Transboundary Water Issues: What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution?

A strong regional economic entity can provide support when issues arise between basin states. The Central Asian Economic Community, now the Central Asian Cooperation Organization, played a key role in mediating between the Aral Sea Basin states when there were difficulties within the International Fund for the Aral Sea. Even though regional economic entities sometimes may be too narrow in their interests, they can provide a stability that basin states may otherwise not have.

Lack of trust and credibility can hinder the process of cooperation. It was apparent during the years of "dormancy" of the International Fund for the Aral Sea that issues of trust and credibility were having a severe effect on the functioning of the organization.

External Links

- Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: Aral Sea — This case was originally incorporated into AquaPedia from the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database organized by Oregon State University. A summary of this case and additional references/resources can be found at this link (Retrieved Jan 7, 2013)

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at:http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Aral_Sea_New.htm

- ^ International Crisis Group. (2002). Central Asia: Water and Conflict. ICG Asia Report N°34. Osh, Brussels.

- ^ Bucknall, J., Klytchnikova, I., Lampietti, J., Lundell, M., Scatasta, M., & Thurman, M. (2009). Irrigation in Central Asia: Social, economic and environmental considerations. The World Bank: Europe and Central Asia Region.

- ^ Dukhovny, V. and V. Sokolov. (2003). Lessons on Cooperation Building to Manage Water Conflicts in the Aral sea Basin. UNESCO-IHP, Technical Documents in Hydrology, N°11

- ^ Micklin,P. (2010). The past, present, and future Aral Sea. Lakes & reservoirs: Research and Management 15:193-213.

- ^ Micklin,P. (2010). The past, present, and future Aral Sea. Lakes & reservoirs: Research and Management 15:193-213.

- ^ Micklin,P. (2010). The past, present, and future Aral Sea. Lakes & reservoirs: Research and Management 15:193-213.

- ^ Micklin, P.P. (2007). The Aral Sea disaster. In: . Jeanloz et al (Eds.), Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 35, 2007, R, pp. 47-72. Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, CA.

- ^ Tursunov, A.A. (1989). The Aral Sea and the ecological situation in Central Asia and Kazakhstan. Gidrotekh. Stroitel. 6, 15-22 (In Russian). Cited in Thurman, 2001.

- ^ O’Hara, S.L., G.F.S. Wiggs, B. Mamedov, G. Davidson and R.B. Hubbard. (2000). Exposure to airborne dust contaminated with pesticides in the Aral Sea region. Lancet Res. Lett. 355, 9204, 19 Feb.

- ^ Nazirov, F.G. (2008). Impact of the Aral crisis on the health of the population. Presentation (in Russian) at International Conference: Problems of the Aral, their influence on the gene fund of the population and the plant and animal world and measures of international cooperation for mitigating their consequences, Tashkent, March 11-12.

- ^ Thurman, M. (2001). Irrigation and poverty in Central Asia: A field assessment. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- ^ Micklin,P. (2010). The past, present, and future Aral Sea. Lakes & reservoirs: Research and Management 15:193-213.

- ^ International Crisis Group. (2002). Central Asia: Water and Conflict. ICG Asia Report N°34. Osh, Brussels.

- ^ Dukhovny, V. and V. Sokolov. (2003). Lessons on Cooperation Building to Manage Water Conflicts in the Aral sea Basin. UNESCO-IHP, Technical Documents in Hydrology, N°11

- ^ Peachey, E.J. (2004). The Aral Sea Basin Crisis and Sustainable Water Resource Management in Central Asia. Journal of Public and International Affairs, Volume 15.

- ^ Gleason, G, (1991). The Struggle for Control over Water in Central Asia: Republican Sovereignty and Collective Action. Report on the USSR 21 (June): 11-18.

- ^ Bucknall, J., Klytchnikova, I., Lampietti, J., Lundell, M., Scatasta, M., & Thurman, M. (2009). Irrigation in Central Asia: Social, economic and environmental considerations. The World Bank: Europe and Central Asia Region.

- ^ Micklin,P. (2010). The past, present, and future Aral Sea. Lakes & reservoirs: Research and Management 15:193-213.

- ^ Dukhovny, V. and V. Sokolov. (2003). Lessons on Cooperation Building to Manage Water Conflicts in the Aral sea Basin. UNESCO-IHP, Technical Documents in Hydrology, N°11

- ^ Micklin, P.P. (1992). The Aral crisis: Introduction to the special Issue. Post-Sov. Geogr. 33(5):269-83.

- ^ Thurman, M. (2001). Irrigation and poverty in Central Asia: A field assessment. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- ^ Gleason, G, (1991). The Struggle for Control over Water in Central Asia: Republican Sovereignty and Collective Action. Report on the USSR 21 (June): 11-18.

- ^ Bucknall, J., Klytchnikova, I., Lampietti, J., Lundell, M., Scatasta, M., & Thurman, M. (2009). Irrigation in Central Asia: Social, economic and environmental considerations. The World Bank: Europe and Central Asia Region.

- ^ Bucknall, J., Klytchnikova, I., Lampietti, J., Lundell, M., Scatasta, M., & Thurman, M. (2009). Irrigation in Central Asia: Social, economic and environmental considerations. The World Bank: Europe and Central Asia Region.

- ^ Thurman, M. (2001). Irrigation and poverty in Central Asia: A field assessment. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- ^ Dukhovny, V. and V. Sokolov. (2003). Lessons on Cooperation Building to Manage Water Conflicts in the Aral sea Basin. UNESCO-IHP, Technical Documents in Hydrology, N°11

- ^ Bucknall, J., Klytchnikova, I., Lampietti, J., Lundell, M., Scatasta, M., & Thurman, M. (2009). Irrigation in Central Asia: Social, economic and environmental considerations. The World Bank: Europe and Central Asia Region

- ^ World Bank. (2000), Republic of Uzbekistan Irrigation and Drainage Sector Study, Vol. 1, pp. 6-7. (Cited in World Bank 2003)

- ^ McKinney, D. C. (1996). Sustainable Water Management in the Aral Sea Basin , Water Resources Update, No. 102, pp. 14-24, 1996.

- ^ Caponera, D. (1987). International Water Resources Law in the Indus Basin. In Water Resources Policy for Asia, ed. M. Ali. Boston: Balkema (4), pp. 509-515.

- ^ Vinogradov, S. (1996). Transboundary Water Resources in the Former Soviet Union: Between Conflict and Cooperation, Natural Resources Journal, Vol 393, pp 406-412.

- ^ McKinney, D. C. (2004). Cooperative management of transboundary water resources in Central Asia. In In the Tracks of Tamerlane-Central Asia's Path into the 21st Century, ed. D. Burghart and T. Sabonis-Helf. Washington DC: National Defense University Press.