Drinking Water Supply in Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Contents

[hide]Summary

The Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority (PPWSA) experienced a sweeping transformation starting in 1993. The public utility went from being an institution that was almost bankrupt and plagued with corruption and inefficiency to one that is now considered a model for good governance and high quality service. The utility currently provides uninterrupted clean water service to over 90 percent (%) of the city of Phnom Penh and has consistently increased its profits since 1993 while also paying consistently higher income taxes to the Cambodian Government and providing subsidies for poor households. The extraordinary success resulted from a combination of legislation that granted the utility financial and operational autonomy, government support, and good leadership. Continued success will depend on the ability of the utility to tackle the main threats that affect urban water: population growth, water scarcity, decreasing water quality and pollution, water overuse, climate change, and infrastructure, institutional, and social problems.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

Background

Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, lies on the confluence of three rivers: the Mekong, Tonle Sap and Bassac rivers (Figure 1). These rivers are the source of freshwater for the city’s population of approximately 1.3 million (approximately 10% of Cambodia’s population) [1][2]. Until the late 1960s, many of the residents of Phnom Penh had an uninterrupted 24-hour water supply of reasonable quality water [3]. Political turmoil that began in the late 1960s and continued for the next two decades took its toll on all of Cambodia’s development sectors including urban water management [3]. During the four-year rule of the Khmer Rouge, from 1975 to 1979, people were forced to evacuate Phnom Penh to work in agriculture in rural areas. All water infrastructure in the city was neglected and water supply was limited to a small group of leaders [4]. In 1979, the PPWSA restarted operations at 45% of its initial capacity [1]. The PPWSA as an institution was dysfunctional and staff were under-qualified, underpaid, unmotivated, and lacked efficiency, which led to consumers receiving very poor service during the next decade [1][3].

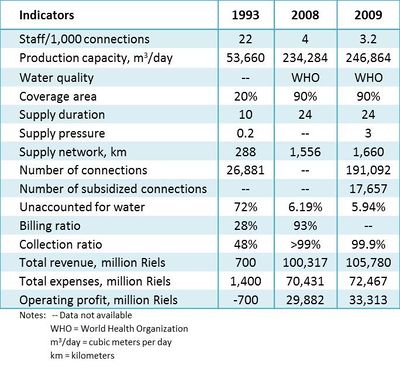

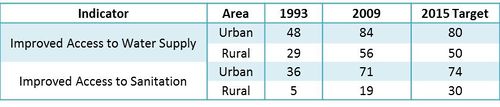

In 1993, the PPWSA initiated a reform process that dramatically improved its performance. During a 15-year period, between 1993 and 2008, the PPWSA increased its annual water production by 437%, the distribution network by 540%, pressure of the system by 1,260%, customer base by 662%, and the number of metered connections by nearly 5,255%. Unaccounted for water (UFW) was reduced from 72% of treated water produced to 6.19% [3]. The PPWSA is a Public Autonomous Institution which has enabled the utility to consistently increase its profits while also paying consistently higher income taxes to the Cambodian Government and providing subsidies for poor households. The number of poor households connected to the system has steadily increased from 101 to 26,778 between 1999 and 2011 [3] [4]. Table 1 shows improvements from 1993 through 2009.

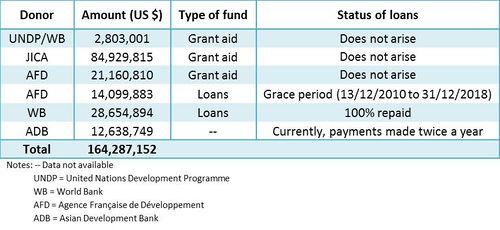

One of the important components that contributed to the improvements of the water utility was donor involvement. The Japan International Co-operation Agency (JICA) has been a major donor since 1991 and continues to provide assistance to the PPWSA on different aspects of water supply, including infrastructure development and management and capacity building[1][3]. JICA also formulated a master plan that served as the road map for operation of the water utility and for coordination of donors [3]. Other donors that have provided support to the PPWSA since 1993 include the Agence Française de Développement (AFD), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the World Bank (WB), and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) [1]. Table 2 shows donor assistance from 1993 through 2009.

Before 1993, the PPWSA was under the control of the governor of the city of Phnom Penh and was run as a government department with no administrative, operational, and financial autonomy[1]. In the 1990s, the Government of Cambodia declared water was an economic and social good and, in 1996, allowed the PPWSA to operate as an independent business-like institution [3]. The Prime Minister also publicly stated in 1997 that everyone, including government institutions and the rich and powerful, had to pay for water services [5]. This allowed the PPWSA to become financially self-sufficient by implementing an increasing-block tariff structure, improving the bill collection ratio, reducing operating costs by improving efficiency, metering all connections, and reducing UFW so that much of the water produced can be sold to consumers [3]. The block-tariff structure was implemented after conducting a socio-economic survey for the city of Phnom Penh to determine the ability and willingness to pay of consumers [3]. A system to provide water to poor households was also implemented and involves providing subsidies between 30% and 100% of the connection fee and charging only 60% of the water bill if the household consumes up to 7 cubic meters per month (m3/month) [3].

Water Quality

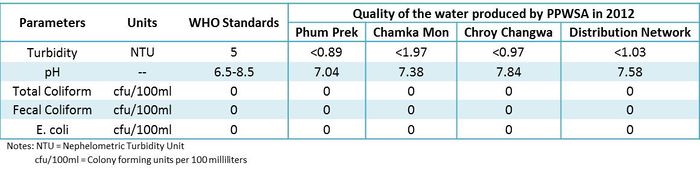

Water supplied by the PPWSA complies with the drinking water standards of the World Health Organization (WHO) and national drinking water standards. PPWSA has three Water Treatment Plants (WTPs). The capacity of Phum Prek WTP is 170,000 m3/day, of Chroy Changva WTP is 140,000 m3/day, and of Chamkar Mon WTP is 20,000 m3/day [4]. The PPWSA tests the quality of treated water three times a day at the WTPs and tests 80 water samples per week at the distribution network. On an annual basis, laboratories in Singapore and Shanghai also test the water samples from the PPWSA [4]. Results for 2012 are shown in Table 3.

Mekong River Basin

Cambodia is located almost completely within the Mekong River Basin and has three major rivers (Mekong, Bassac and Tonle Sap) that are the main source of water for Phnom Penh [3][6]. The Mekong River traverses six countries, has a diverse freshwater ecosystem, and supports the livelihood of approximately 70 million people living within the basin [7]. China and Myanmar are part of the Upper Mekong Basin and Lao PDR, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam of the Lower Mekong Basin [7]. The river is characterized by a cycle of flooding and drought that has created a rich ecosystem but also continues to claim lives and cause major economic loses [8]. The Tonle Sap Lake is the heart of the Mekong’s aquatic production, an invaluable flood-leveler and an essential source of income for the region[6]. Water level in the Mekong River rises during the rainy season (May through October) and flows up the Tonle Sap River into the Tonle Sap Lake. During the dry season (November through April), levels of the Mekong River decrease and water flows out of the Tonle Sap Lake through the Tonle Sap River and contributes approximately 16% of dry season flow of the Mekong River [9]. Upstream development projects on the Mekong River Basin could severely reduce the volume and seasonality of flow of the Mekong River, which could have potentially destructive impacts on Cambodia’s floodplain and aquatic production, but also on the available drinking water resources of Phnom Penh [6][9].

Riparian countries have long considered development projects on the Mekong River Basin as one the main options to alleviate poverty and limit the negative effects of floods and droughts in the region [7]. In the 1950s, the United Nations (UN) and the United States (US) recommended construction of hydropower dams in the Mekong River and its tributaries to limit flooding, produce electricity, and support development of the region [10]. The push from the UN and US towards cooperation and development had less to do with local needs and more with fighting Communism that was in the rise in Southeast Asia [10]. With the support of the UN, the governments of the Lower Mekong Basin established the Mekong Committee (MC) in 1957 to promote, coordinate, and supervise water development projects [11]. Burma (now Myanmar) did not join the Committee because of political and geographical reasons and China was excluded because it was not a member of the UN [11].

During the first 15 years since its creation, the MC focused primarily on oversight of national projects in the tributaries of the Mekong River and on hydrologic data collection [12]. Hundreds of studies were conducted on agriculture, fisheries, geology, among others, to support hydropower, irrigation, and navigation projects that were never constructed due to wars in the region [13]. Cambodia, under the rule of the Khmer Rouge, left the MC in 1975 [12]. Lao PDR, Vietnam and Thailand continued to cooperate and established the Interim Mekong Committee (IMC) in 1978 [12]. However, the IMC did not have authority to oversee national projects and served more as a diplomatic battleground between the three countries than as a cooperation agency [6] [14]. In 1991, Cambodia, under a new government, requested the MC be reestablished and the country’s membership reactivated [6]. Since the political, social and economic situation in the region had changed, Thailand did not want the rules of the 1957 MC to take effect and prompted a new round of negotiations [14]. In 1995, Lao PDR, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam signed the “Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin” (henceforth the 1995 Mekong Agreement) and established the Mekong River Commission (MRC) [11]. Although not specifically stated, the goals of the agreement were consistent with the concept of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), which aims to provide economic wellbeing by managing water and related resources without compromising social equity and environmental sustainability[7]. China did not sign the agreement but, along with Myanmar, became a dialogue member of the MRC in 1996 and, in 2002 began sharing limited hydrological data on the Mekong River[6].

The 1995 Mekong Agreement established a framework for cooperation placing emphasis on joint sustainable development and reasonable and equitable water use [11]. That last point proved to be a contentious issue during negotiations. All parties agreed that reasonable and equitable water use required maintaining a minimum monthly natural flow on the mainstream during dry and wet seasons, prevention of large peak flows during the wet season, and a system for reviewing proposed water projects in the Basin [14]. The focus of the 1995 Mekong Agreement is on sustainable and comprehensive management of water and related resources of the Mekong River Basin with an emphasis on joint social and economic development, ecological protection, and water allocation [7]. Sustainable development and management in the 1995 Mekong Agreement is specifically targeted but not limited to irrigation, hydropower, navigation, flood control, fisheries, timber floating, and recreation and tourism [15]. Nonetheless, the MRC continued to place emphasis on hydropower projects during its initial years without making progress in areas of water utilization and environmental protection [10]. A water utilization program was started in 1996 but the majority of procedures and guidelines, including for maintenance of flows on the mainstream, were established between 2003 and 2006 [10].

International cooperation for management of water resources of the Mekong River Basin began over 50 years ago. One of the major strengths of the cooperation agreement and the institutions responsible for its implementation has been their ability to adapt to changing political, social, and economic conditions in Southeast Asia. There has, nonetheless, been limited progress on sustainable management of water resources of the Mekong River Basin mainly because of the time it took to make the new institution and related policies operational, lack of enforcement mechanisms, and absence of important stakeholders from the agreement. The MRC required over a decade to develop procedures and guidelines for water development projects in the basin and even now lacks the power to enforce them, and the two upstream riparian countries are not members of the MRC. Cambodia, being a downstream country, has potentially the most to lose from uncontrolled upstream development of the river as a result of potentially destructive impacts on the country’s floodplain and aquatic production [6].

The 1995 Mekong Agreement emphasized territorial integrity and sovereignty and rejected the enforcement power of the MRC [6]. Since the MRC’s established procedures and guidelines do not bind the actions of the member countries, the organization has appeared more as a coordinating, rather than regulating agency of the use of water resources [7][10]. This has led to an increasing number of unilateral and bilateral plans for water development, mainly related to hydropower, that do not address possible consequences to the ecosystem of the basin and to other riparian countries [6]. Most riparian countries in the Upper and Lower Basins have plans to expand or begin hydropower development projects in the Mekong River and its tributaries. China, the most upstream country in the basin, has ongoing construction of a cascade of eight dams in the mainstream of the Mekong River, which has raised concerns of potential environmental, economic, and social impacts to the downstream countries [16]. The absence of China and Myanmar from the Agreement continues to be a limiting factor to integrated basin management, but there seems to be very little incentive, especially for China, to join the Mekong cooperation [16]. The MRC has made significant progress towards integrated management of the Mekong River Basin but future success will depend on its ability to improve cooperation between Lower Basin countries, and to build a stronger relationship with Upper Basin countries.

Governance

Cambodia

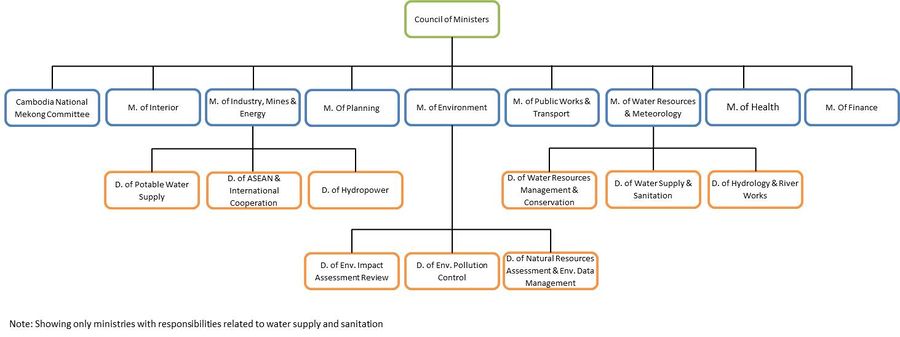

In the aftermath of the Rio Summit, the government of Cambodia established in 1993 the Ministry of the Environment (MoE) and in 1996 instituted the Law on Environmental Protection and Natural Resources Management [17]. MoE is responsible for environmental planning, monitoring of effluents discharged to natural waterways and storm water drains, and coordination with other ministries, including the Cambodia National Mekong Committee (CNMC), the Ministry of Interior (MoI), Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy (MIME), Ministry of Planning (MoP), Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT), and the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology (MoWRAM) (Figure 2) [2][18]. The MoWRAM has direct authority over watershed management, water resource monitoring, and hydropower production, and conducts technical review and monitoring of all water resource construction activities in Cambodia [19]. The Ministry of Finance (MoF) is responsible for allocating annual budgets to the water supply and sanitation sectors and the Ministry of Health (MoH) is responsible for setting water supply and wastewater drinking standards [2]. The government has set specific targets for 2015 based on the Millennium Development Goals to improve access to water and sanitation in Cambodia (Table 4).

In 1996, the government of Cambodia instituted Decree No. 52 which granted all public institutions with economic characteristics legal independence [3]. Continuing the process of decentralization, Cambodia passed in 1998 the Organic Law giving legal responsibility to provinces and districts to administer development plans, including projects related to water supply and sanitation. The MoI is responsible for implementing the government’s decentralization framework and the Organic Law [2]. The MIME is responsible for urban and provincial water supply and has also supported the decentralization process by giving more autonomy to individual Water Supply Authorities (WSAs). However, with the exception of the PPWSA, provincial WSAs lack technical knowledge and institutional capacity to provide reliable water service [2].

Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority

The PPWSA was established in 1959 by Royal Decree No. 164NS as a state treatment and business unit under the jurisdiction of the MoI and direct supervision of the Phnom Penh Municipality [1] [4]. The water utility was run as a government department with no administrative, operational and financial autonomy and it needed continuous municipal authorization for all its operational expenditures [1]. With the landmark Decree No. 52 of 1996, the PPWSA was allowed to operate as an independent business-like institution without political interference [3]. The institution was placed under the supervision of the MIME and the MoF [20].

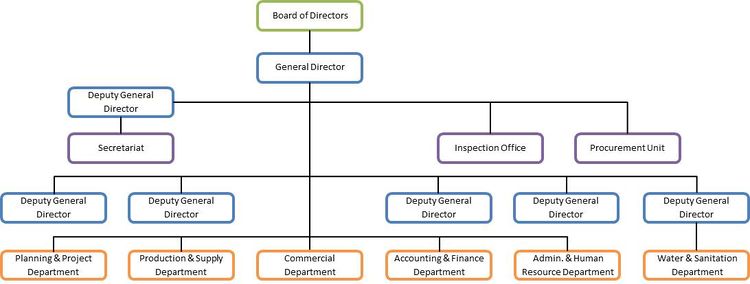

The current organizational structure of PPWSA (Figure 3) consists of a Board of Directors, a General Director, six departments with a secretariat directly reporting to the Deputy General Director and an inspection office and procurement unit directly handled by the General Director.

The Board of Directors has seven members including one representative from MIME that acts as the Chairman, the General Director of the PPWSA, one member each from the Council of Ministers, the MoF, the Phnom Penh Municipality, and the MoI, and one PPWSA staff representative [21]. The Secretariat is responsible for all information, documentation and assisting the activities of the Board of Directors. The duties of the Inspection Office include researching, inspecting, and recording the consumption of potable water and settling customer claims [4].

The PPWSA prepares an annual investment plan that has to be approved by the Board of Directors, and the tutelage ministries, which are the MIME and the MoF. The General Director must also submit to the Board of Directors an annual plan which must include financing plans, operational budget, and price of water and other services. The General Director is appointed for a three-year period by the Prime Minister, after receiving nomination from the tutelage ministries, and can be reappointed to any number of additional terms thereafter [1].

In the early 1990s, the PPWSA had under-qualified staff that faced below subsistence pay, absence of incentives and accountability, and pervasive corruption [3]. Under the direction of Ek Sonn Chan (the General Director since 1993), the PPWSA underwent a major structural reorganization that decentralized its internal operations and placed planning responsibility and accountability within each operating department [1]. Incentives, like higher salaries and bonuses for good performance were instituted as well as penalties for poor performance. The utility has continued to improve its management practices by training staff regularly through in-house workshops with internal and external experts, supporting advanced academic degrees for selected staff, and attending international training sessions organized by donor agencies, like JICA and UNDP [1].

The Problem

Government policies of decentralization and autonomy of public utilities, combined with good leadership and management, contributed to the extraordinary success of the PPWSA which currently supplies over 90% of the city of Phnom Penh with uninterrupted clean drinking water. Nonetheless, the utility still faces current and future challenges. In a World Wildlife Fund 2011 report, Katalina Engel et al identify the main threats to urban water as population growth, water scarcity, decreasing water quality and pollution, water overuse, climate change, and infrastructure, institutional, and social problems [22].

Water scarcity and water overuse

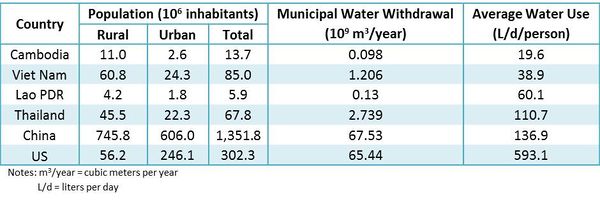

Water scarcity has not been a concern for the PPWSA because Cambodia has high annual rainfall (up to approximately 3,000 millimeters in the highlands), three major rivers (Mekong, Bassac and Tonle Sap), and excellent sources of groundwater both in terms of quantity (estimated to be around 17.6 billion m3) and quality [2] [3]. The three rivers provide all of Phnom Penh’s drinking water but could see their flows reduced in the future because of upstream development of the Mekong River Basin and climate change. Water scarcity may become a problem when reduced flows are combined with population growth and increasing per capita water use. Table 5 shows a comparison of per capita water consumption between Cambodia, other countries in the region, and the US using data from 2003 to 2007. Per capita water use in Cambodia was approximately 19.6 liters per day (L/d) compared to 136.9 L/d in China and 593.1 L/d in the US [23]. Water consumption is however much higher in Phnom Penh that in the rest of Cambodia and has increased since the 1990s. The inhabitants of Phnom Penh consumed approximately 90 L/d/ person in 1995 and 160 L/d/person in 2010 [1][3].

Population growth and infrastructure and social problems

In 2008, approximately 19.5% of the population of Cambodia lived in urban areas, with the majority residing in the city of Phnom Penh and its outskirts [2]. While the annual growth rate for Cambodia has been approximately 2.5%, Phnom Penh is growing annually by approximately 4% [24]. As of 2013, the PPWSA had a total water production capacity of 330,000 m3/day which was sufficient to provide reliable service to its customers and continue with its coverage expansion plans (300% expansion by 2020) [4][21]. Nonetheless, population growth, increasing per capita water use, tourism, and expansion of the service area will continue to put pressure on existing urban infrastructure. To meet those increasing demands, the PPWSA authority estimated that production capacity has to be increased to 500,000 m3/day by 2020 [3][21]. It is likely that the PPWSA will be able to meet that new requirement if it continues with its commitment to provide safe drinking water to the city of Phnom Penh and with its good management and operation practices.

Urban growth has been inextricably linked with slum expansion and poverty in most developing countries, and Cambodia is not the exception [22]. In 2005, over 30% of Phnom Penh’s population lived without adequate housing and basic services (as cited in [24]). Due to increasing development and land demand, the municipality has moved poor communities from the center to the outskirts of the city, which has in many cases decreased the living standards of the poor and their access to services. In 2008, only approximately 30% of people living in poor settlements in Phnom Penh and its outskirts had a central piped water connection [24]. In 2004, approximately 76% of the city’s population had access to basic sanitation, compared to only 30% access for poor households (as cited in [24]). Sanitation coverage is not the responsibility of the PPWSA but of the Cambodian Public Works and Transport Ministry [24]. Nonetheless, increasing water supply also results in an increase in wastewater that, if not properly treated and discharged, can have negative impacts on water quality and the environment.

Decreasing water quality and pollution

The city of Phnom Penh obtains its drinking water from three rivers, the Mekong, the Bassac, and the Tonle Sap. Pollution and decreasing water quality of these rivers is a growing problem because of poor sanitation coverage and discharge practices, lack of solid waste disposal mechanisms, agricultural runoff, industrial wastewater, and river bank erosion.

The majority of households in the city center of Phnom Penh are connected to a combined sewerage system consisting of underground pipes (built mostly in the 1960s) that discharge into main open interceptor sewers [25][26]. Since there is no wastewater treatment plant in Phnom Penh, the interceptor sewers discharge 10% of effluents directly into the Mekong River without any treatment. The remaining 90%, which amounted to approximately 55,600 m3/day in 2004, is discharged into three natural treatment wetlands [25][26]. More than 3,000 industrial firms located in and around Phnom Penh also discharge their untreated effluents into the wetlands [26]. Although the wetlands have been shown to effectively treat waste, they continue to pose a risk to settlers that grow vegetables in the area [25][26]. Moreover, filling-in of the natural wetlands to provide land for new development in the city began in 2010, which could have significant impacts in local flooding, water quality, and capability of treating waste [25]. The inhabitants of Phnom Penh that don’t have sewer connections usually have septic tanks that are emptied by private operators. Those operators may dump the waste at unregulated sites or, for a fee, at a sanitary landfill site [2]. The situation is much different in poor settlements where residents use public toilets, open pits that are shared by multiple families, or defecate into water, open fields or plastic bags [24]. As a result of the lack of city-wide sanitation coverage and wastewater treatment, water supplies in Phnom Penh have been shown to be polluted with bacteria or chemical contamination (as cited in [24]).

Climate change

The effects of climate change in Cambodia are expected to be increases in temperature, shifts in timing and duration of seasons (shorter, wetter rainy seasons and longer, drier dry seasons), increase frequency and intensity of floods and droughts, and sea level rise in coastal areas [27]. These changes will have significant impacts on agricultural production, fisheries, poverty, groundwater recharge and viability, and surface water availability, quality and distribution [2][27]. One of the major challenges for the city of Phnom Penh and the PPWSA will be changes in seasonality and the volume of flow in the Mekong River, which would increase flooding in the wet season and cause water shortages during the dry season [2].

Institutional problems

The PPWSA transformed itself from a dysfunctional, near bankrupt and corrupt institution to a well-managed, efficient and profitable water utility [3]. Lessons learned from this remarkable transformation could be used in other regions of Cambodia and the world to improve operations of public institutions. In Cambodia, the MIME is giving more autonomy to individual WSAs in an attempt to duplicate the PPWSA model. It is currently running pilot programs in two provinces (Battambang and Siem Reap) with technical assistance from the PPWSA [2]. In terms of potential water scarcity due to lower flows in the Mekong River, the PPWSA must rely on the MRC to coordinate and negotiate development plans on the Mekong River Basin while preventing negative impacts on the sustainability of water resources in Cambodia. Unfortunately, the MRC does not have enforcing power over its member countries and the two upper riparian countries, China and Myanmar, are not members of the institution. This has led to an increasing number of unilateral and bilateral plans to begin or expand hydropower development projects, mainly in Lao PDR and China. Cambodia, being a downstream country, has much to lose if those projects change seasonality or volume of flow of the Mekong River.

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:Drinking water supply in Phnom Penh – problem-shed, policy-shed and watershed

Contributed by: Tania Alarcon (last edit: 20 May 2013)

- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Das, B., Chan, E. S., Visoth, C., Pangare, G., and Simpson, R., eds. (2010). Sharing the Reforms Process, Mekong Water Dialogue Publication No. 4, Gland, Switzerland: IUCN

- ^ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Asian Development Bank. (2012). Cambodia: Water supply and sanitation sector assessment, strategy, and road map. Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong City, Philippines

- ^ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 Biswas, A. K., and Tortajada, C. (2010). Water Supply of Phnom Penh: An Example of Good Governance. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 26:2, 157-172, June 14

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority. (2013). History. Organization Structure. Production System. Distribution System. Water Quality. Non Revenue Water. Retrieved from: www.ppwsa.com.kh/en/index.php?page=history

- ^ Asian Development Bank. (2010). Every drop counts: Learning from good practices in eight Asian cities. Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong City, Philippines

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Keskinen, M., Mehtonen, K., and Varis, O. (2008). Transboundary cooperation vs. internal ambitions: The role of China and Cambodia in the Mekong region. In International Water Security: Domestic Threats and Opportunities, Edited by: Pachova, N. I., Nakayama, M. and Jansky, L., United Nations University Press, Tokyo, Japan, pp. 79-109

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Mehtonen K., Keskinen, M. and Varis, O. (2008). The Mekong: IWRM and institutions. In Management of transboundary rivers and lakes, Edited by: Varis, O., Tortajada, C. and Biswas, A.K. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp.207–226

- ^ Mekong River Commision. (2013). Mekong Basin Planning. The Story Behind the Basin Development Plan. Retrieved from Mekong River Commission: www.mrcmekong.org/assets/Publications/basin-reports/BDP-Story-2013-small.pdf

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Campbell, I. C., Poole, C., Giesen, W., and Valbo-Jorgensen, J. (2006). Species diversity and ecology of Tonle Sap Great Lake, Cambodia. Aquatic Sciences, 68: 355–373

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Ha, M.L. (2011). The role of regional institutions in sustainable development: a review of the Mekong River commission’s first 15 years. Journal of Sustainable Development, 5(1): 125–140

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Radosevich, G. E., Olson, D.C. (1999). Existing and Emerging Basin Arrangements in Asia: Mekong River Commission Case Study. Third Workshop on River Basin Institution Development, June 24 1999. The World Bank, Washington DC

- ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Sneddon, C., Fox, C. (2006). Rethinking transboundary waters: A critical hydropolitics of the Mekong basin. Political Geography, 25(2): 181–202

- ^ Varis, O., Rahaman, M. M., and Stucki, V. (2008). The Rocky Road from Integrated Plans to Implementation: Lessons Learned from the Mekong and Senegal River Basins. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 5(1): 103-121

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Browder, G. (2000). An Analysis of the Negotiations for the 1995 Mekong Agreement. International Negotiations, 5: 237-261

- ^ Mekong River Commision (MRC). (2011a). 1995 Mekong Agreement and Procedures. Retrieved from: Mekong River Commission: www.mrcmekong.org/assets/Publications/policies/MRC-1995-Agreement-n-procedures.pdf

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Moder, F., Kuenzer, C., Xu, Z., Leinenkugel, P., and Van Quyen, B. (2012). IWRM for the Mekong Basin. In The Mekong Delta System: Interdisciplinary Analyses of a River Delta, Edited by: Renaud, F. G., and Kuenzer, C., Nederland: Springer, pp. 133-165

- ^ Tan, A. KJ. (2002). Recent Institutional Developments on the Environment in South East Asia - A Report Card on the Region. Singapore Journal of International & Comparative Law, 6: 891- 908

- ^ Water Environment Partnership in Asia (WEPA). (2013). Organizational Arrangement: Cambodia. Retrieved from: www.wepa-db.net/policies/structure/chart/cambodia/index.htm

- ^ Oberndorf, R. B. (2004). Comparative Analysis of Policy and Legislation related to Watershed Management in Cambodia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. Working Paper 07. MRC-GTZ Cooperation Programme, Phnom Penh

- ^ Phnom Penh Water Supply Authority (PPWSA). (2011). Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 December 2011. Phnom Penh, Kingdom of Cambodia

- ^ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Chan, E. S. (2009). Bringing Safe Water to Phnom Penh's City. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 25:4, 597-609, November 18

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Engel, K., Jokiel, D., Kraljevic, A., Geiger, M., Smith, and K. (2011). Big cities. Big water. Big Challenges. Water in an urbanizing world. World Wildlife Fund, Koberich, Germany

- ^ FAO. (2013). AQUASTAT database - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Retrieved from: www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/data/query/results.html

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 Heinonen, U. (2008). Millennium Development Goals and Phnom Penh: Is the city on track to meet the goals? In Modern Myths of the Mekong, Edited by: Kummu, M., Keskinen, M. and Varis, O., Helsinki University of Technology – TKK, Helsinski, pp. 95-105

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Irvine, K. and Koottatep, T. (2010). Guest Editorial: Natural Wetlands Treatment of Sewage Discharges from Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Successes and Future Challenges. Asian Journal of Water, Environment and Pollution, 7(3)

- ^ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Muong, S. (2004). Avoiding Adverse Health Impacts from Contaminated Vegetables: Options for Three Wetlands in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia, Research Report No. 2004-RR5, Singapore

- ^ 27.0 27.1 Ministry of Environment and United Nations Development Programme. (2011). Cambodia Human Development Report 2011. Building Resilience: The Future of Rural Livelihoods in the Face of Climate Change. Phnom Penh, Cambodia