Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (Middle East)

| Geolocation: | 33° 19' 55.2166", 44° 22' 1.2799" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 61,696,14061,696,140,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 822,786822,786 km² 317,677.675 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type), Arid/desert (Köppen B-type), Dry-summer, Dry-winter |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban, religious/cultural sites |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation |

| Water Features: | Jordan River |

Contents

Summary

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

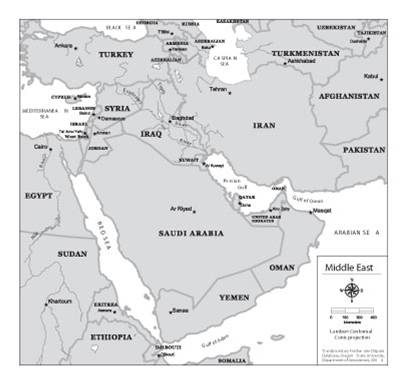

Image 1. Map of all water resources of the Middle East.[1]

Image 1. Map of all water resources of the Middle East.[1]

Background

By 1991, several events combined to shift the emphasis on the potential for 'hydro-conflict' in the Middle East to the potential for "hydro-cooperation." The first event was natural, but limited to the Jordan River basin. Three years of below-average rainfall caused a dramatic tightening in the water management practices of each of the riparians- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestinians and Syria -including rationing, cut-backs to agriculture by as much as 30%, and restructuring of water pricing and allocations. Although these steps placed short-term hardships on those affected, they also showed that, for years of normal rainfall, there was still some flexibility in the system. Most water decision-makers agree that these steps, particularly regarding pricing practices and allocations to agriculture, were long overdue.

The next series of events were geo-political, and region-wide, in nature. The Gulf War in 1990 and the collapse of the Soviet Union caused a re-alignment of political alliances in the Mideast, which finally made possible the first public face-to-face peace talks between Arabs and Israelis, in Madrid on October 30, 1991. This breakthrough was followed by an organizational meeting in Moscow in January 1992, which established a multilateral track that would act alongside the bilateral track. The multilateral track focuses collaboration efforts on five regionally relevant subjects, including the Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (MWGWR). The "Core Parties" of this group are Israel, the West Bank/Gaza and Jordan.

The Problem

Until the current Arab-Israeli peace negotiations began in 1991, attempts at Middle East conflict resolution had either endeavored to tackle political or resource problems, always separately. By separating the two realms of "high" and "low" politics, some have argued, each process was doomed to fail. In water resource issues-the Johnston Negotiations of the mid-1950s, attempts at "water-for-peace" through nuclear desalination in the late 1960s, negotiations over the Yarmouk River in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Global Water Summit Initiative of 1991-all addressed water qua water, separate from the political differences between the parties. All failed to one degree or another.

While political tensions have precluded any comprehensive agreement over the waters of the Middle East, unilateral development in each country has tried to keep pace with the water needs of growing populations and economies. As a result, demand for water resources in most of the countries in the region exceeds at least 90% of the renewable supply, the only exceptions being Lebanon and Turkey . All of the countries and territories riparian to the Jordan River-Israel, Syria, Jordan, and the West Bank-are currently using between 95% and more than 100% of their annual renewable freshwater supply. Gaza exceeds its renewable supplies by 50% every year, resulting in serious saltwater intrusion. In recent dry years, water consumption has routinely exceeded annual supply, the difference usually being made up through overdraft of fragile groundwater systems.

In water systems as tightly managed and exploited as those of the Middle East, any future unilateral development is likely to be extremely expensive if based on technology, or dangerously politically volatile if threatening the resources of a neighbor. It has been clear to water managers for years that the most viable options include regional cooperation as a minimum prerequisite.

Attempts at Conflict Management

Since the opening session of the multilateral talks in Moscow in January 1992, the Working Group on Water Resources, with the United States as "gavel-holder," has been the venue by which problems of water supply, demand and institutions has been raised among the parties to the bilateral talks, with the exception of Lebanon and Syria-Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinians-as well as among the Arab states from the Gulf and the Maghreb. These include Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen . Participating in the talks are also "non-regional delegations," including representatives from governments such as Canada, China, the European Union, Japan, and Turkey, and from donor NGOs, such as the World Bank. The complete list of parties invited to each round includes representatives from Algeria, Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Belgium, Canada, China, Denmark, European Union, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kuwait, Luxembourg, Mauritania, Morocco, Netherlands, Norway, Oman, Palestine, Portugal, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United Nations, United States, the World Bank, and Yemen.

The two tracks of the current negotiations, the bilateral and the multilateral, are explicitly designed not only to close the gap between issues of politics and issues of regional development, but perhaps to use progress in these areas to help catalyze the pace of the other, in a positive feedback loop towards "a just and lasting peace in the Middle East." The idea is that the multilateral working groups would provide forums for relatively free dialogue on the future of the region and, in the process, allow for personal ice-breaking and confidence building to take place. Given the role of the Working Group on Water Resources in this context, the objectives have been more on the order of fact-finding and workshops, rather than tackling the difficult political issues of water rights and allocations, or the development of specific projects. Likewise, decisions are made through consensus only.

The Working Group on Water has met five times (Table 1). The pace of success of each round has vacillated but, in general, has been increasing. The "second" round, the first of the water group alone, has been characterized as "contentious," with initial posturing and venting on all sides. Palestinians and Jordanians, then part of a joint delegation, first raised the issue of water rights, claiming that no progress can be made on any other issue until past grievances are addressed. In sharp contrast, the Israeli position has been that the question of water rights is a bilateral issue, and that the multilateral working group should focus on joint management and development of new resources. Since decisions are made by consensus, little progress was made on either of these issues. Nevertheless, plans were made for continuation of the talks-an achievement in and of itself.

The third round in Washington, DC, in September 1992 made somewhat more progress. Consensus was reached on a general emphasis for the watersheds that the U.S. State Department had proposed in May, focusing on four subjects: enhancement of water data; water management practices; enhancement of water supply, and concepts for regional cooperation and management.

Progress was also made on the definition of the relationship between the multilateral and bilateral tracks. By this third meeting, it became clear that regional water-sharing agreements, or any political agreements surrounding water resources, would not be dealt with in the multilaterals, but that the role of these talks was to deal with non-political issues of mutual concern, thereby strengthening the bilateral track. The goal in the Working Group on Water Resources became to plan for a future region at peace, and to leave the pace of implementation to the bilaterals. This distinction between "planning" and "implementation" became crucial, with progress only being made as the boundary between the two is continuously pushed and blurred by the mediators.

The fourth round in Geneva in April 1993 proved particularly contentious, threatening at points to grind the process to a halt. Initially, the meeting was to be somewhat innocuous. Proposals were made for a series of intersessional activities surrounding the four subjects agreed to at the previous meeting. These activities, including study tours and water-related courses, would help capacity building within while fostering better personal and professional relations.

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreNo ASI articles have been added yet for this case

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at:http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Middle_East_New.htm