Integrated Management and Negotiations for Equitable Allocation of Flow of the Jordan River Among Riparian States

| Geolocation: | 32° 9' 25.245", 35° 33' 6.3281" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 1212,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 4280042,800 km² 16,525.08 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Arid/desert (Köppen B-type), Continental (Köppen D-type), Dry-winter |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban- high density, religious/cultural sites |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation |

| Water Features: | Jordan River |

| Water Projects: | |

| Agreements: | Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace |

Contents

Summary

The Jordan River flows between five particularly contentious riparians, two of which rely on the river as the primary water supply. By the early-1950s, there was little room for any unilateral development without impacting on other riparian states. The initial issue was an equitable allocation of the annual flow of the Jordan watershed between its riparian states- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Egypt also was included, given its preeminence in the Arab world. Until the current Arab-Israeli peace negotiations, which began in 1991, political or resource problems were always handled separately. The initiatives which were addressed as strictly water resource issues, namely-the Johnston Negotiations of the mid-1950s, attempts at "water-for-peace" through nuclear desalination in the late 1960s, negotiations over the Yarmuk River in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Global Water Summit Initiative of 1991, all failed to one degree or another, because they were handled separately from overall political discussions. The resolution of water resources issues then had to await the Arab-Israeli peace talks to meet with any tangible progress. The pace of success of each round of talks has vacillated but, in general, has been increasing. The goal in the Working Group on Water Resources became to plan for a future region at peace, and to leave the pace of implementation to the bilateral talks. This distinction between "planning" and "implementation" became crucial, with progress only being made as the boundary between the two is continuously pushed and blurred by the mediators. Multilateral activities have helped set the stage for agreements formalized in bilateral negotiations-the Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace[1] of 1994, and the Interim Agreements between Israel and the Palestinians (1993 and 1995). For the first time since the states came into being, the Israel-Jordan peace treaty legally spells out mutually recognized water allocations. The Interim Agreement also recognizes the water rights of both Israelis and Palestinians, but defers their quantification until the final round of negotiations.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

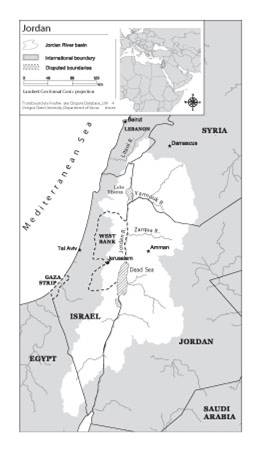

Figure 1. Map of the Jordan River and tributaries (directly and indirectly, including Litani) [2]

Figure 1. Map of the Jordan River and tributaries (directly and indirectly, including Litani) [2]

The Problem

The Jordan River flows between five particularly contentious riparians, two of which rely on the river as the primary water supply. By the early-1950s, there was little room for any unilateral development without impacting on other riparian states. The initial issue was an equitable allocation of the annual flow of the Jordan watershed between its riparian states- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Egypt also was included, given its preeminence in the Arab world. Since water was (and is) deeply related to other contentious issues of land, refugees, and political sovereignty. The Johnston negotiations, named after U.S. special envoy Eric Johnston, attempted to mediate the dispute over water rights among all the riparians in the mid-1950s.

Until the current Arab-Israeli peace negotiations, which began in 1991, political or resource problems were always handled separately. Some experts have argued that by separating the two realms of "high" and "low" politics, each process was doomed to fail. The initiatives which were addressed as strictly water resource issues, namely-the Johnston Negotiations of the mid-1950s, attempts at "water-for-peace" through nuclear desalination in the late 1960s, negotiations over the Yarmuk River in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Global Water Summit Initiative of 1991, all failed to one degree or another, because they were handled separately from overall political discussions. The resolution of water resources issues then had to await the Arab-Israeli peace talks to meet with any tangible progress.

Attempts at Conflict Management

Johnston’s initial proposals were based on a study carried out by Charles Main and the Tennessee Valley Authority at the request of UNRWA to develop the area's water resources and to provide for refugee resettlement. The TVA addressed the problem with a regional approach, pointedly ignoring political boundaries in their study. In the words of the introduction, "the report describes the elements of an efficient arrangement of water supply within the watershed of the Jordan River System. It does not consider political factors or attempt to set this system into the national boundaries now prevailing."

The major features of the Main Plan included small dams on the Hasbani, Dan, and Banias, a medium size (175 MCM storage) dam at Maqarin, additional storage at the Sea of Galilee, and gravity flow canals down both sides of the Jordan Valley. Preliminary allocations gave Israel 394 MCM/yr, Jordan 774 MCM/yr, and Syria 45 MCM/yr. (see Table 1). In addition, the Main Plan described only in-basin use of the Jordan River water, although it conceded that "it is recognized that each of these countries may have different ideas about the specific areas within their boundaries to which these waters might be directed"; and excluded the Litani River.

Israel responded to the "Main Plan" with the "Cotton Plan," which it allocated Israel 1290 MCM/yr, including 400 MCM/yr from the Litani, Jordan 575 MCM/yr, Syria 30 MCM/yr, and Lebanon 450 MCM/yr. In contrast to the Main Plan, the Cotton Plan called for out-of-basin transfers to the coastal plain and the Negev; included the Litani River; and recommended the Sea of Galilee as the main storage facility, thereby diluting its salinity.

In 1954, representatives from Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt established the Arab League Technical Committee under Egyptian leadership and formulated the "Arab Plan." Its principal difference from the Johnston Plan was in the water allocated to each state. Israel was to receive 182 MCM/yr, Jordan 698 MCM/yr, Syria 132 MCM/yr, and Lebanon 35 MCM/yr, in addition to keeping all of the Litani. The Arab Plan reaffirmed in-basin use; excluded the Litani; and rejected storage in the Galilee, which lies wholly in Israel.

Johnston worked until the end of 1955 to reconcile U.S., Arab, and Israeli proposals in a Unified Plan amenable to all of the states involved. His dealings were bolstered by a U.S. offer to fund two-thirds of the development costs. His plan addressed the objections of both sides, and accomplished no small degree of compromise, although his neglect of groundwater issues would later prove an important oversight. Though they had not met face to face for these negotiations, all states agreed on the need for a regional approach. Israel gave up on integration of the Litani and the Arabs agreed to allow out-of-basin transfer. The Arabs objected, but finally agreed, to international supervision of withdrawals and construction. Allocations under the Unified Plan, later known as the Johnston Plan, included 400 MCM/yr to Israel, 720 MCM/yr to Jordan, 132 MCM/yr to Syria and 35 MCM/yr to Lebanon (Table 1).

Although the agreement was never ratified, both sides have generally adhered to the technical details and allocations, even while proceeding with unilateral development. Agreement was encouraged by the United States, which promised funding for future water development projects only as long as the Johnston Plans allocations were adhered to. Since that time to the present, Israeli and Jordanian water officials have met several times a year, as often as every two weeks during the critical summer months, at so-called "Picnic Table Talks" at the confluence of the Jordan and Yarmuk Rivers to discuss flow rates and allocations.

Table 1. Water Allocations from the Johnston Negotiations, in MCM/year

| Plan | Israel | Jordan | Lebanon | Syria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main | 393 | 774 | - | 45 |

| Cotton (Israel1) | 1290 | 575 | 450 | 30 |

| Arab | 182 | 698 | 35 | 132 |

| Unified | 4002 | 7203 | 35 | 132 |

- Cotton Plan included integration of the Litani River into the Jordan Basin.

- Unified Plan allocated Israel the "residue" flow, what remained after the Arab States withdrew their allocations, estimated at an average of 409 MCM/year

- Two different summaries were distributed after the negotiations, with a difference of 15 MCM/year on allocations between Israel and Jordan on the Yarmuk River. This difference was never resolved and was the focus of Yarmuk negotiations in the late 1980s

Outcome

The technical committees from both sides accepted the Unified Plan, and the Israeli Cabinet approved it without vote in July 1955. President Nasser of Egypt became an active advocate because Johnston 's proposals seemed to deal with the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Palestinian problem simultaneously. Among other proposals, Johnston envisioned the diversion of Nile water to the western Sinai Desert to resettle two million Palestinian refugees.

Despite the forward momentum, the Arab League Council decided not to accept the plan in October 1955 because of the political implications of accepting, and the momentum died out. As noted above, the agreement was never ratified, but both sides have generally adhered to the allocations.

Negotiations Over the Yarmuk River

Although the watershed-wide scope of the Johnston negotiations has not been taken advantage of, the allocations which resulted have been at the heart of ongoing attempts at water conflict resolution, particularly along the Yarmuk River, where a dam for storage and hydroelectric power generation has been suggested since the early 1950s.

In 1952, Miles Bunger, an American attached to the Technical Cooperation Agency in Amman, first suggested the construction of a dam at Maqarin to help even the flow of the Yarmuk River and to tap its hydroelectric potential. The following year, Jordan and UNRWA signed an agreement to implement the Bunger plan the following year, including a dam at Maqarin with a storage capacity of 480 MCM and a diversion dam at Addassiyah, and Syria and Jordan agreed that Syria would receive 2/3 of the hydropower generated, in exchange for Jordan's receiving 7/8 of the natural flow of the river. Dams along the Yarmuk were also included in the Johnston negotiations-the Main Plan included a small dam, 47 meters high with a storage capacity of only 47 MCM, because initial planning called for the Sea of Galilee to be the central storage facility. As Arab resistance to Israeli control over Galilee storage became clear in the course of the negotiations, a larger dam, 126 meters high with a storage capacity of 300 MCM was included.

While the idea faded with the Johnston negotiations, the idea of a dam on the Yarmuk was raised again in 1957, in a Soviet-Syrian Aid Agreement, and at the First Arab Summit in Cairo in 1964, as part of the All-Arab Diversion Project. Construction of the diversion dam at Mukheiba was actually begun, but was abandoned when the borders shifted after the 1967 war-one side of the projected dam in the Golan Heights shifted from Syrian to Israeli territory.

The Maqarin Dam was resurrected as an idea in Jordan 's Seven Year Plan in 1975, and Jordanian water officials approached their Israeli counterparts about the low dam at Mukheiba in 1977. While the Israelis proved amenable at a ministerial-level meeting in Zurich -a more-even flow of the river would benefit all of the riparians-the Israeli government shifted that year to one less interested in the project.

This stalemate might have continued except for strong U.S. involvement in 1980, when President Carter pledged a $9 million loan towards the Maqarin project, and Congress approved an additional $150 million-provided that all of the riparians agree. Philip Habib was sent to the region to help mediate an agreement. While Habib was able to gain consensus on the concept of the dam, on separating the question of the Yarmuk from that of West Bank allocations, and on the difficult question of summer flow allocations-25 MCM would flow to Israel during the summer months-negotiations were hung up winter flow allocations, and final ratification was never reached.

Syria and Jordan reaffirmed mutual commitment to a dam at Maqarin in 1987, whereby Jordan would receive 75% of the water stored in the proposed dam, and Syria would receive all of the hydropower generated. The agreement called for funding from the World Bank, which insists that all riparians agree to a project before it can be funded. Israel refused until its concerns about the winter flow of the river were addressed.

Against this backdrop, Jordan in 1989 approached the U.S. Department of State for help in resolving the dispute. Ambassador Richard Armitage was dispatched to the region in September 1989 to resume indirect mediation between Jordan and Israel where Philip Habib had left off a decade earlier. The points raised during the following year were as follows:

Both sides agreed that 25 MCM/yr would be made available to Israel during the summer months, but disagreed as to whether any additional water would be specifically earmarked for Israel during the winter months.

The overall viability of a dam was also open to question-the Israelis still thought that the Sea of Galilee ought to be used as a regional reservoir, and both sides questioned what effects ongoing development by Syria at the headwaters of the Yarmuk would have on the dam's viability. Since the State Dept. had no mandate to approach Syria, their input was missing from the mediation. Israel eventually wanted a formal agreement with Jordan, a step which would have been politically difficult for the Jordanians at the time.

By fall of 1990, agreement seemed to be taking shape, by which Israel agreed to the concept of the dam, and discussions on a formal document and winter flow allocations could continue during construction, estimated for more than five years. Two issues held up any agreement. First, the lack of Syrian input left questions of the future of the river unresolved, a point noted by both sides during mediation. Second, the outbreak of the Gulf War in 1991 overwhelmed other regional issues, finally preempting talks on the Yarmuk. The issue has not been brought up again until recently in the context of the Arab-Israeli peace negotiations.

In the absence of an agreement, both Syria and Israel are currently able to exceed their allocations from the Johnston accords, the former because of a series of small storage dams and the latter because of its downstream riparian position. Syria began building a series of small impoundment dams upstream from both Jordan and Israel in the mid-1980s., while Israel has been taking advantage of the lack of a storage facility to increase its withdrawals from the river. Syria currently has 27 dams in place on the upper Yarmuk, with a combined storage capacity of approximately 250 MCM (its Johnston allocations are 90 MCM/yr. from the Yarmuk), and Israel currently uses 70-100 MCM/yr (its Johnston allocation are 25-40 MCM/yr). This leaves Jordan approximately 150 MCM/yr for the East Ghor Canal (as compared to its Johnston allocations of 377 MCM/yr).

By 1991, several events combined to shift the emphasis on the potential for 'hydro-conflict' in the Middle East to the potential for 'hydro-cooperation.' The Gulf War in 1990 and the collapse of the Soviet Union caused a realignment of political alliances in the Mideast that finally made possible the first public face-to-face peace talks between Arabs and Israelis, in Madrid on October 30, 1991. During the bilateral negotiations between Israel and each of its neighbors, it was agreed that a second track be established for multilateral negotiations on five subjects deemed 'regional,' including water resources.

Since the opening session of the multilateral talks in Moscow in January 1992, the Working Group on Water Resources, with the United States as "gavel-holder," has been the venue by which problems of water supply, demand and institutions has been raised among the parties to the bilateral talks, with the exception of Lebanon and Syria. The two tracks of the current negotiations, the bilateral and the multilateral, are designed explicitly not only to close the gap between issues of politics and issues of regional development, but perhaps to use progress on each to help catalyze the pace of the other, in a positive feedback loop towards "a just and lasting peace in the Middle East." The idea is that the multilateral working groups would provide forums for relatively free dialogue on the future of the region and, in the process, allow for personal ice-breaking and confidence building to take place. Given the role of the Working Group on Water Resources in this context, the objectives have been more on the order of fact-finding and workshops, rather than tackling the difficult political issues of water rights and allocations, or the development of specific projects. Likewise, decisions are made through consensus only.

The pace of success of each round of talks has vacillated but, in general, has been increasing. By this third meeting in 1992, it became clear that regional water-sharing agreements, or any political agreements surrounding water resources, would not be dealt with in the multilaterals, but that the role of these talks was to deal with non-political issues of mutual concern, thereby strengthening the bilateral track. The goal in the Working Group on Water Resources became to plan for a future region at peace, and to leave the pace of implementation to the bilateral talks. This distinction between "planning" and "implementation" became crucial, with progress only being made as the boundary between the two is continuously pushed and blurred by the mediators.

The multilateral activities have helped set the stage for agreements formalized in bilateral negotiations-the Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace of 1994, and the Interim Agreements between Israel and the Palestinians (1993 and 1995). For the first time since the states came into being, the Israel-Jordan peace treaty legally spells out mutually recognized water allocations. Acknowledging that, "water issues along their entire boundary must be dealt with in their totality," the treaty spells out allocations for both the Yarmuk and Jordan Rivers, as well as regarding Arava/Araba ground water, and calls for joint efforts to prevent water pollution. Also, "[recognizing] that their water resources are not sufficient to meet their needs," the treaty calls for ways of alleviating the water shortage through cooperative projects, both regional and international. The Interim Agreement also recognizes the water rights of both Israelis and Palestinians, but defers their quantification until the final round of negotiations.

Issues and Stakeholders

Negotiating an equitable allocation of the flow of the Jordan River and its tributaries between the riparian states; developing a rational plan for integrated watershed development.

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Governance, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Sovereign state/national/federal government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Development/humanitarian interest, Community or organized citizens

The Jordan River flows between five particularly contentious riparians, two of which rely on the river as the primary water supply.

Stakeholders:

- Israel

- Jordan

- Lebanon

- Palestine

- Syria

- West Bank

- Egypt

- Golan Heights

- U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA)

- U.S. and Russia (sponsoring multilateral negotiations)

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:Jordan River: Lessons learned and creative outcomes

Contributed by: Aaron T. Wolf, Joshua T. Newton, Matthew Pritchard (last edit: 12 February 2013)

Key Questions

Urban Water Systems and Water Treatment: What approaches are most beneficial for rapidly growing cities in the developing world to link water management to sustainable urban growth strategy?

All of the water resources in the basin ought to be included in the planning process. Ignoring the relationship between quality and quantity, and between surface- and groundwater, ignores hydrological reality. Groundwater was not explicitly dealt with in the Plan, and is currently the most pressing issue between Israel and Palestinians. Likewise, tensions have flared over the years between Israel and Jordan over Israel’s diverting saline springs into the lower Jordan, increasing the salinity of water on which Jordanian farmers rely.

Transboundary Water Issues: What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution?

In highly conflictual settings, separating resource issues from political interests may not be a productive strategy. Eric Johnston took the approach that the process of reaching a rational watershed management plan:

- May, itself, act as a confidence-building catalyst for increased cooperation in the political realm, and

- May help alleviate the burning political issues of refugees and land rights.

By approaching peace through water, however, several overriding interests remained unmet in the process. The plan finally remained unratified mainly for political reasons.

Issues of national sovereignty which were unmet during the process included:

- The Arab states saw a final agreement with Israel as recognition of Israel, a step they were not willing to make at the time.

- Some Arabs may have felt that the plan was devised by Israel for its own benefit and was 'put over' on the U.S.

The plan allowed the countries to use their allotted water for whatever purpose they saw fit. The Arabs worried that if Israel used their water to irrigate the Negev (outside the Jordan Valley), that the increased amount of agriculture would allow more food production, which would allow for increased immigration, which might encourage greater territorial desires on the part of Israel.

Influence Leadership and Power: To what extent can international actors and movements from civil society influence water management? How and when is this beneficial/detrimental and how can these effects be supported/mitigated?

Including key non-riparian parties can be useful to reaching agreement; excluding them can be harmful. Egypt was included in the negotiations because of its preeminence in the Arab world, and despite its non-riparian status. Some attribute the accomplishments made during the course in part to President Nasser's support.

In contrast, pressure after the negotiations from other Arab states not directly involved in the water conflict may have had an impact on its eventual demise. Iraq and Saudi Arabia strongly urged Lebanon, Syria and Jordan not to accept the Plan. Perhaps partially as a result, Lebanon said they would not enter any agreement that split the waters of the Hasbani River or any other river.

Influence Leadership and Power: How does asymmetry of power influence water negotiations and how can the negative effects be mitigated?

Issues of national sovereignty can manifest itself through the need for each state to control its own water source and/or storage facilities. The Johnston Plan provided that some winter flood waters be stored in the Sea of Galilee, which is entirely in Israeli territory. The Arab side was reluctant to relinquish too much control of the main storage facility. Likewise, Israel had the same kinds of control reservations about a water master.

External Links

- Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) (2012). Oregon State University. Jordan River Basin Case Study. — The Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) is used to aid in the assessment of the process of water conflict prevention and resolution. Over the years we have developed this Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, a project of the Oregon State University Department of Geosciences, in collaboration with the Northwest Alliance for Computational Science and Engineering.

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at: http://ocid.nacse.org/tfdd/tfdddocs/538ENG.pdf

- ^ Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) (2012). Oregon State University. Available on-line at:http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Jordan_New.htm