Case Study of Transboundary Dispute Resolution: Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (Middle East)

| Geolocation: | 33° 19' 55.2166", 44° 22' 1.2799" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 61,696,14061,696,140,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 822,786822,786 km² 317,677.675 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type), Arid/desert (Köppen B-type), Dry-summer, Dry-winter |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban, religious/cultural sites |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation |

| Water Features: | Jordan River |

Contents

Summary

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

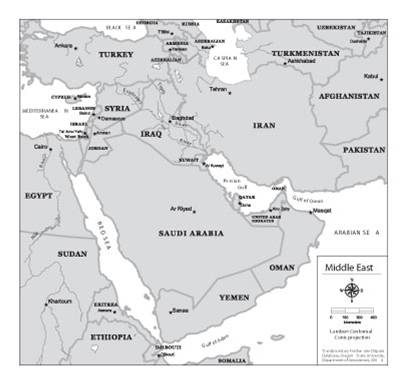

Image 1. Map of all water resources of the Middle East.[1]

Image 1. Map of all water resources of the Middle East.[1]

Background

By 1991, several events combined to shift the emphasis on the potential for 'hydro-conflict' in the Middle East to the potential for "hydro-cooperation." The first event was natural, but limited to the Jordan River basin. Three years of below-average rainfall caused a dramatic tightening in the water management practices of each of the riparians- Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestinians and Syria -including rationing, cut-backs to agriculture by as much as 30%, and restructuring of water pricing and allocations. Although these steps placed short-term hardships on those affected, they also showed that, for years of normal rainfall, there was still some flexibility in the system. Most water decision-makers agree that these steps, particularly regarding pricing practices and allocations to agriculture, were long overdue.

The next series of events were geo-political, and region-wide, in nature. The Gulf War in 1990 and the collapse of the Soviet Union caused a re-alignment of political alliances in the Mideast, which finally made possible the first public face-to-face peace talks between Arabs and Israelis, in Madrid on October 30, 1991. This breakthrough was followed by an organizational meeting in Moscow in January 1992, which established a multilateral track that would act alongside the bilateral track. The multilateral track focuses collaboration efforts on five regionally relevant subjects, including the Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources (MWGWR). The "Core Parties" of this group are Israel, the West Bank/Gaza and Jordan.

The Problem

Until the current Arab-Israeli peace negotiations began in 1991, attempts at Middle East conflict resolution had either endeavored to tackle political or resource problems, always separately. By separating the two realms of "high" and "low" politics, some have argued, each process was doomed to fail. In water resource issues-the Johnston Negotiations of the mid-1950s, attempts at "water-for-peace" through nuclear desalination in the late 1960s, negotiations over the Yarmouk River in the 1970s and 1980s, and the Global Water Summit Initiative of 1991-all addressed water qua water, separate from the political differences between the parties. All failed to one degree or another.

While political tensions have precluded any comprehensive agreement over the waters of the Middle East, unilateral development in each country has tried to keep pace with the water needs of growing populations and economies. As a result, demand for water resources in most of the countries in the region exceeds at least 90% of the renewable supply, the only exceptions being Lebanon and Turkey . All of the countries and territories riparian to the Jordan River-Israel, Syria, Jordan, and the West Bank-are currently using between 95% and more than 100% of their annual renewable freshwater supply. Gaza exceeds its renewable supplies by 50% every year, resulting in serious saltwater intrusion. In recent dry years, water consumption has routinely exceeded annual supply, the difference usually being made up through overdraft of fragile groundwater systems.

In water systems as tightly managed and exploited as those of the Middle East, any future unilateral development is likely to be extremely expensive if based on technology, or dangerously politically volatile if threatening the resources of a neighbor. It has been clear to water managers for years that the most viable options include regional cooperation as a minimum prerequisite.

Attempts at Conflict Management

Since the opening session of the multilateral talks in Moscow in January 1992, the Working Group on Water Resources, with the United States as "gavel-holder," has been the venue by which problems of water supply, demand and institutions has been raised among the parties to the bilateral talks, with the exception of Lebanon and Syria-Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinians-as well as among the Arab states from the Gulf and the Maghreb. These include Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen . Participating in the talks are also "non-regional delegations," including representatives from governments such as Canada, China, the European Union, Japan, and Turkey, and from donor NGOs, such as the World Bank. The complete list of parties invited to each round includes representatives from Algeria, Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Belgium, Canada, China, Denmark, European Union, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kuwait, Luxembourg, Mauritania, Morocco, Netherlands, Norway, Oman, Palestine, Portugal, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United Nations, United States, the World Bank, and Yemen.

The two tracks of the current negotiations, the bilateral and the multilateral, are explicitly designed not only to close the gap between issues of politics and issues of regional development, but perhaps to use progress in these areas to help catalyze the pace of the other, in a positive feedback loop towards "a just and lasting peace in the Middle East." The idea is that the multilateral working groups would provide forums for relatively free dialogue on the future of the region and, in the process, allow for personal ice-breaking and confidence building to take place. Given the role of the Working Group on Water Resources in this context, the objectives have been more on the order of fact-finding and workshops, rather than tackling the difficult political issues of water rights and allocations, or the development of specific projects. Likewise, decisions are made through consensus only.

The Working Group on Water has met five times (Table 1). The pace of success of each round has vacillated but, in general, has been increasing. The "second" round, the first of the water group alone, has been characterized as "contentious," with initial posturing and venting on all sides. Palestinians and Jordanians, then part of a joint delegation, first raised the issue of water rights, claiming that no progress can be made on any other issue until past grievances are addressed. In sharp contrast, the Israeli position has been that the question of water rights is a bilateral issue, and that the multilateral working group should focus on joint management and development of new resources. Since decisions are made by consensus, little progress was made on either of these issues. Nevertheless, plans were made for continuation of the talks-an achievement in and of itself.

The third round in Washington, DC, in September 1992 made somewhat more progress. Consensus was reached on a general emphasis for the watersheds that the U.S. State Department had proposed in May, focusing on four subjects: enhancement of water data; water management practices; enhancement of water supply, and concepts for regional cooperation and management.

Progress was also made on the definition of the relationship between the multilateral and bilateral tracks. By this third meeting, it became clear that regional water-sharing agreements, or any political agreements surrounding water resources, would not be dealt with in the multilaterals, but that the role of these talks was to deal with non-political issues of mutual concern, thereby strengthening the bilateral track. The goal in the Working Group on Water Resources became to plan for a future region at peace, and to leave the pace of implementation to the bilaterals. This distinction between "planning" and "implementation" became crucial, with progress only being made as the boundary between the two is continuously pushed and blurred by the mediators.

The fourth round in Geneva in April 1993 proved particularly contentious, threatening at points to grind the process to a halt. Initially, the meeting was to be somewhat innocuous. Proposals were made for a series of intersessional activities surrounding the four subjects agreed to at the previous meeting. These activities, including study tours and water-related courses, would help capacity building within while fostering better personal and professional relations.

Table 1. Meetings of the Multilateral Working Group on Water Resources of the Middle East.

| Dates | Location | |

|---|---|---|

| Multilateral organizational meeting 1A | 28-29 January 1992 | Moscow |

| Water Talks, Round 2 | 14-15 May 1992 | Vienna |

| Water Talks, Round 3 | 16-17 September 1992 | Washington, DC |

| Water Talks, Round 4 | 27-29 April 1993 | Geneva |

| Water Talks, Round 5 | 26-28 October 1993 | Beijing |

| Water Talks, Round 6 | 17-19 April 1994 | Muscat |

A After some confusion in numbering, it was eventually officially decided that the multilateral organizational meeting in Moscow represented the first round of the multilateral working groups. Subsequent meetings are therefore numbered correspondingly, beginning with two.

The issue of water rights was raised again, however, with the Palestinians threatening to boycott the intersessional activities. The Jordanians, who had already agreed to discuss water rights with the Israelis in their bilateral negotiations, helped work out a similar arrangement on behalf of the Palestinians. Agreement was not reached at the time, but both sides agreed later after quiet negotiations in May, before the meeting of the working group on refugees in Oslo . The agreement called for three Israeli-Palestinian working groups within the bilateral negotiations, one of which would deal with water rights. The agreement, in which the Palestinians agreed to participate in the intersessional activities, also called for U.S. representatives of the water working group to visit the region. While some may have expected the U.S. representatives to take the opportunity of the visit to take a strong proactive position on the issue of water rights, the delegates adhered to the stance that any specific initiatives would have to come from the parties themselves, and that agreement would have to be by consensus.

By July 1993, the intersessional activities had begun, including approximately 20 activities as diverse as a study tour of the Colorado River basin and a series of seminars on semi-arid lands that focused on capacity building in the region. A series of fourteen courses was designed by the U.S. and the EU for participants from the region, to range in length from two weeks to 12 months, and to cover subjects as broad as concepts of integrated water management and as detailed as groundwater flow modeling.

Following a June 1993 agreement in the multilaterals on a joint US/EC proposal to conduct a regional training needs assessment in the Middle East water sector, a team of specialists developed a Priority Regional Training Action Plan. The plan includes a series of fourteen courses to be offered to managers and professionals from the region over two years commencing in June 1994. The courses were endorsed at the sixth round of water talks in Oman in April 1994. In the end, 20 courses were given to 275 participants from the Middle East . The courses ranged in duration from two weeks to two years (Sidebar 1).

On 15 September 1993, the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements was signed between Palestinians and Israelis, which defined Palestinian autonomy and the redeployment of Israeli forces out of Gaza and Jericho . Among other issues, the Declaration of Principles called for the creation of a Palestinian Water Administration Authority. Moreover, the first item in Annex III, on cooperation in economic and development programs, included a focus on cooperation in the field of water, including a Water Development Program prepared by experts from both sides, which will also specify the mode of cooperation in the management of water resources in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and will include proposals for studies and plans on water rights of each party, as well as on the equitable utilization of joint water resources for implementation in and beyond the interim period.

Sidebar 1 Regional Training Action Plan

Water sector level courses:

# Concepts of integrated water resources planning and management

# Water resources assessment, planning and management

# Water quality management

# Data collection and management systems

# Alternatives in water resources development

# Principles and applications of international water law

Water sub-sector level courses:

7. Management of municipal water supply systems

8. Rehabilitation of municipal water supply systems

9. Management of wastewater collection and treatment systems

10. Development of efficient irrigation systems

Specialized courses:

11. Environmental impact assessment techniques

12. Groundwater modeling

13. Public awareness campaigns for the water sector

14. Development, management and delivery of training programs in the water sector

Annex IV describes regional development programs for cooperation, including:

* Development of a joint Israeli-Palestinian-Jordanian Plan for coordinated exploitation of the Dead Sea area; * The Mediterranean Sea ( Gaza ) - Dead Sea Canal ; * Regional desalinization and other water development projects; * Regional plan for agricultural development, including a coordinated regional effort for the prevention of desertification.

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreNo ASI articles have been added yet for this case

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at:http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Middle_East_New.htm