Difference between revisions of "US-Canada Columbia River Management"

| [unchecked revision] | [pending revision] |

m (Saved using "Save and continue" button in form) |

|||

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

|Population=7 | |Population=7 | ||

|Area=670000 | |Area=670000 | ||

| − | |Geolocation=48.9998584, -117. | + | |Geolocation=48.9998584, -117.8320186 |

|Issues={{Issue | |Issues={{Issue | ||

|Issue=Canadian Entitlement. How should Canada be compensated for power benefits from downstream power generation? | |Issue=Canadian Entitlement. How should Canada be compensated for power benefits from downstream power generation? | ||

|Issue Description=Water storage in British Columbia allows for more predictability and control over the entire Columbia River Basin, thus hydropower facilities in the US Pacific Northwest can produce power more efficiently. The treaty requires the US to sell 50% of the estimated downstream power generated to Canada at a fixed cost. In revisiting this treaty, the US feels it is allotting too much power to Canada, while Canada feels like the share is justified and could be higher. | |Issue Description=Water storage in British Columbia allows for more predictability and control over the entire Columbia River Basin, thus hydropower facilities in the US Pacific Northwest can produce power more efficiently. The treaty requires the US to sell 50% of the estimated downstream power generated to Canada at a fixed cost. In revisiting this treaty, the US feels it is allotting too much power to Canada, while Canada feels like the share is justified and could be higher. | ||

| − | Stakeholders | + | |

| − | + | Stakeholders<br/> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | * US State Department | |

| − | + | * Canadian State Department | |

| − | + | * US Army Corp of Engineers | |

| − | + | * Bonneville Power Administration, US federal power authority stationed in Oregon | |

| + | * BC Hydro and Power Authority, British Columbia’s public power authority | ||

| + | * Other electricity companies | ||

|NSPD=Governance; Assets | |NSPD=Governance; Assets | ||

|Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency | |Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency | ||

| Line 20: | Line 22: | ||

|Issue=Flood Protection. How should flood storage be operated so that the basin is protected from flooding without a large disruption to business-as-usual operations? | |Issue=Flood Protection. How should flood storage be operated so that the basin is protected from flooding without a large disruption to business-as-usual operations? | ||

|Issue Description=The Columbia River Treaty defines two types of flood protection that Canada provides to the US, “Assured” for day-to-day operations and “Called Upon” for emergencies. The treaty only guarantees assured flood protection until 2024, even if the treaty itself is not terminated. Called Upon flood storage will be the only measure if the treaty is not revised. The US and Canada disagree on when it is appropriate to call upon this measure. | |Issue Description=The Columbia River Treaty defines two types of flood protection that Canada provides to the US, “Assured” for day-to-day operations and “Called Upon” for emergencies. The treaty only guarantees assured flood protection until 2024, even if the treaty itself is not terminated. Called Upon flood storage will be the only measure if the treaty is not revised. The US and Canada disagree on when it is appropriate to call upon this measure. | ||

| − | Stakeholders | + | |

| − | + | Stakeholders<br /> | |

| − | + | * US State Department | |

| − | + | * Canadian State Department | |

| − | + | * US Army Corp of Engineers | |

| − | + | * Bonneville Power Administration, US federal power authority stationed in Oregon | |

| − | + | * BC Hydro and Power Authority, British Columbia’s public power authority | |

| + | * Communities along the river | ||

|NSPD=Water Quantity; Ecosystems; Governance | |NSPD=Water Quantity; Ecosystems; Governance | ||

|Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency | |Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency | ||

| Line 32: | Line 35: | ||

|Issue=Ecosystem Services. How can the US and Canadian entities ensure minimum damage to fish and surrounding ecosystems in the basin? | |Issue=Ecosystem Services. How can the US and Canadian entities ensure minimum damage to fish and surrounding ecosystems in the basin? | ||

|Issue Description=The 1964 treaty only covers power and flood related issues and ignores environmental and ecosystem issues. Dams have killed off many salmon and steelhead populations. The new treaty should include clauses on protecting the ecosystem and revitalizing fish populations. | |Issue Description=The 1964 treaty only covers power and flood related issues and ignores environmental and ecosystem issues. Dams have killed off many salmon and steelhead populations. The new treaty should include clauses on protecting the ecosystem and revitalizing fish populations. | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Stakeholders<br /> | |

| − | + | *US State Department | |

| − | + | *Canadian State Department | |

| − | + | *US Army Corp of Engineers | |

| − | + | *Bonneville Power Administration, US federal power authority stationed in Oregon | |

| − | + | *BC Hydro and Power Authority, British Columbia’s public power authority | |

| − | + | *First Nations and Indigenous Communities | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | Stakeholders | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

|NSPD=Ecosystems; Values and Norms | |NSPD=Ecosystems; Values and Norms | ||

|Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens | |Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens | ||

}} | }} | ||

|Key Questions={{Key Question | |Key Questions={{Key Question | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Subject=Hydropower Dams and Large Storage Infrastructure | |Subject=Hydropower Dams and Large Storage Infrastructure | ||

|Key Question - Dams=Where does the benefit “flow” from a hydropower project and how does that affect implementation and sustainability of the project? | |Key Question - Dams=Where does the benefit “flow” from a hydropower project and how does that affect implementation and sustainability of the project? | ||

| Line 141: | Line 64: | ||

|Agreement=Columbia River Treaty | |Agreement=Columbia River Treaty | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | |REP Framework=== Overview == | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Columbia River Treaty is a 1964 agreement between the United States of America and Canada over the management of the Columbia River. The treaty is due for renewal or termination in 2024, so both countries are currently planning for renegotiation. Issues include disagreement between the two sides over flood storage and the sharing of generated hydropower. The original treaty did not consider the environment or ecosystem services, and the revised treaty is likely to contain provisions for this topic. The state departments of the two countries are the negotiators for the treaty renewal. The US entities (Army Corp of Engineers and Bonneville Power Administration) and the Canadian entity (BC Hydro and Power Authority) who are in charge of managing the 1964 treaty have both submitted recommendations about renegotiation to their respective state departments. State governments, indigenous groups, and local communities are also impacted by the treaty renewal, but have smaller voices in the negotiations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Geographic, Natural, and Historic Framework of the Columbia River Basin== | ||

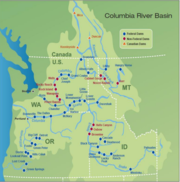

| + | [[File:Columbia River Basin.png|thumbnail|Columbia River Basin]] | ||

| + | === Columbia River Basin Geography and Services === | ||

| + | Stretching more than 1200 miles, the Columbia River is the fourth largest river in North America in terms of flow rate. The basin encompasses British Columbia in Canada and Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and little bit of California and Nevada in the United States. About 15% of the land area of the 259,000 sq. mile basin is in Canada, the upstream country, but Canadian waters account for about 38% of the average annual volume (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The river provides services to both wildlife and human populations. The Columbia River is home to many species of fish (especially salmon) and their migration and reproduction cycles (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). As one of the most dammed rivers in the world, the basin provides a setting for more than 40% of total US and 92% of British Columbia hydropower generation (Lillis, 2014). In addition, the Columbia River is a source of recreation, transportation, and irrigation for the area. | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Historical Background=== | ||

| + | The International Joint Commission (IJC) was formed by the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1910 to manage US-Canada transboundary waters. Its responsibilities include regulating shared water uses, investigating transboundary issues, and recommending solutions. The IJC consists of six commissioners, three appointed by the federal governments of each country, who are expected to operate independently of the countries once they are appointed. Starting in 1944, the IJC spent over a decade conducting a study on the management of the Columbia River Basin, ultimately recommending principles for sharing flood control and electric power benefits (International Joint Commission, 2017). Two major events triggered the IJC’s recommendation for a treaty: the building of the Grand Coulee Dam and the Vanport disaster. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Grand Coulee Dam was constructed between 1933 and 1941 in Northeast Washington State by the US Bureau of Reclamation. Just before completion, the US government applied for a permit with the IJC to operate the dam, conceding that water levels may increase at the Canadian border because of this reservoir. Since the dam was mostly completed by the time the application was received, the IJC approved it with a loose promise of revisiting the issue if water levels become problematic. The building of this dam effectively eliminated many salmon and steelhead runs in the region (Harrison, 2011). Additionally, uncontrolled water flows prevented the dam from achieving its maximum efficiency (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). The Grand Coulee Dam is currently the largest electricity producing facility in the United States (US EIA, 2016). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Vanport was Oregon’s second largest city in the first half of the 1900’s. On May 30, 1948, after a snowy winter, a flood twenty-three feet tall fell upon the city. The surge of water was eight feet above the dikes that were in place, so the town was almost entirely wiped out. Approximately 18,500 residents were displaced and over a hundred people are estimated to have died. The deaths and displacement resulted from a combination of poor flood protection and assurances from the Housing Authority of Portland that the dikes would hold (Geiling, 2015). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Grand Coulee Dam and the flooding of Vanport, Oregon caused the International Joint Commission to establish the International Columbia River Engineering Board to conduct a study to investigate different dam sites and recommend a course of action for the area. The board recommended the development of upstream storage, which would help regulate water flows and allow for better power generation and dependability at downstream dams, as well as flood protection (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). These recommendations culminated in the creation of the Columbia River Treaty. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==The Columbia Treaty== | ||

| + | ===Major Components of the Treaty=== | ||

| + | The Columbia Treaty was signed by representatives from the US and Canada on January 17th, 1961 and was ratified by both countries on September 16th, 1964. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The treaty tasked specific entities with implementation in their respective countries. The US entities consisted of the Northwest Division Engineer of the US Army Corp of Engineers, responsible for building and operating dams, and the administrator of the Bonneville Power Administration, a federal agency responsible for marketing the generated power. The Canadian entity consisted of the British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (BC Hydro), responsible for managing dams and marketing power on the Canadian side. The treaty also established the Permanent Engineering Board (PEB), which is tasked with monitoring and reporting results being achieved under the treaty, as well as reconciling any technical or operation disagreements between the entities. Each country appoints two members who act independently of the countries once appointed. The US representatives are appointed by the US Secretary of the Army and the Secretary of Energy. The Canadian representatives are appointed by the Canadian federal government and the British Columbian government (Columbia Treaty, 1961). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The treaty calls for an expansion of flood storage in the basin through the building of four new dams. Canada built the Duncan Dam in 1968, Hugh Keenleyside/Arrow Dam in 1969, and the Mica Dam in 1973. The United States built the Libby Dam on the Kootenai River (a tributary of the Columbia) in 1973. These four dams effectively doubled the storage capacity of the basin (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Permanent Engineering Board was tasked with maintaining the Flood Control Operating Plan, which dictates flood and power management in the basin as a whole and is updated once a while (the most recent instance was 2003). The PEB, the US entities, and the Canadian entity are also responsible for preparing an Assured Operating Plan (AOP) for the operation of Canadian flood storage five years in advance of each operating year (Columbia Treaty, 1961). | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the major components of the treaty is the sharing of downstream power benefits between the US and Canada. The existence of upstream Canadian dams allows for more dependable and efficient hydropower generation in the whole region. Thus, Canada is entitled to 50% of estimated downstream power benefits, as defined in each year’s AOP. This means that the US is required to sell this amount to Canada at a flat rate. The treaty defines this downstream power benefit as “the difference in the hydroelectric power capable of being generated in the United States of America with and without the use of Canadian storage, determined in advanced” (Columbia Treaty, 1961). Canada sold the initial $254 million, or about thirty-years’ worth, of power to US utility companies (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The other major component of the treaty is the two types of flood protection. “Assured” flood protection is defined in each year’s AOP, which dictates how Canada should operate their storage year to year to prevent flooding in the US. The US paid Canada for sixty-years’ worth of assured flood protection in one lump sum in the 1960’s, which went to pay for Canada’s three new dams. The other type of flood protection is “Called Upon” protection, which is for emergency events. This method dictates that Canada must “when called upon by an entity designated by the United States of America for that purpose, operate within the limits of existing facilities any storage in the Columbia River basin in Canada as the entity requires to meet flood control needs for the duration of the flood control period for which the call is made” (Columbia Treaty, 1961). Called Upon flood protection has never been requested in the history of the treaty, but if it were to be requested, the US would pay Canada a flat fee for each of the first four times the provision is enacted, as well as immediately deliver power to British Columbia to compensate for the loss in power generation (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The lifetime of the Columbia Treaty is sixty years. Either country can terminate this treaty after September 16th, 2024, provided that they give at least ten years’ notice. If the treaty is not terminate or revised, most provisions continue as-is. A notable exception is that “Assured” flood protection ends in 2024 regardless of treaty renewal, since the US has only paid Canada for sixty years’ worth of this protection. If the treaty is terminated, the US will no longer be required to pay the Canadian Entitlement (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). 2014 is ten years before possible termination, so both countries have been preparing to revisit the treaty. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Evaluating the Columbia Treaty=== | ||

| + | Over the last fifty years, the Columbia Treaty has shaped the landscape of water and electricity in the Pacific Northwest. The building of the Pacific Northwest-Southwest Intertie, a system of high voltage transmission lines running from British Columbia to California, has provided reliable power trading in the region. The Army Corp of Engineers, Bonneville Power Administration, and the US Bureau of Reclamation signed the Pacific Northwest Coordination Agreement, uniting most of the hydro projects in the area under one utility, optimizing operations (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). In addition, it is estimated that assured flood protection has saved the US over $7309.2 million between 1964 and 2005 (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite being an example of sound transboundary cooperation, the treaty does have its flaws. First, there is a lack of environmental or ecologic provisions. The Columbia River system impacts thirteen different species of salmon and steelhead under the Endangered Species Act, which regulates the harm that the US can do to certain animals. (Endangered Species Act, 1973). Second, the creation of the new dams flooded hundreds of thousands of acres of land and displaced timber production, wildlife, farming, recreation, tourism and settlements (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). These effects are disproportionately felt by local communities and indigenous groups that rely on the river for work and play. The same stakeholders were the ones to be left out in negotiations for the 1964 treaty and will continue to be left out if negotiations are only at higher levels of governance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The treaty renewal process has potential in fixing the issues presented here. Over the last few years, various groups have compiled recommendations on how to proceed with negotiations before 2024. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Columbia Treaty Renewal== | ||

| + | ===Regional Recommendations for Treaty Renewal=== | ||

| + | In 2013, both countries’ entities published regional recommendations to their respective countries on how to proceed with negotiations. The US Entity’s recommendations, compiled by the Army Corp of Engineers and Bonneville Power Administration, called for modernizing the current treaty to meet regional needs for irrigation, municipal and industrial use, in-stream flows, navigation, and recreation, in addition to the flood and power provisions already in place. The document advocated for adaptability in the new treaty to account for climate change and new technologies, as well as minimizing adverse effects to indigenous communities. The Canadian Entitlement and Called Upon operations are currently seen as unfair by the US. These recommendations included input from a sovereign review team consisting of representatives from the four Northwest states, fifteen tribes, and the Northwest Federal Caucus, as well as consultation with regional interest groups and utility companies (U.S. Entity Regional Recommendation for the Future of the Columbia River Treaty after 2024, 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Canadian Entity’s recommendations, compiled by BC Hydro, are similar to the US’s. There is a call to modernize the treaty in order to account for climate change, navigation, water supply, and ecosystems. The Entity recommends seeking ways to maximize power benefits without impacting the environment or recreational activities. They also would like a revisit for the Canadian Entitlement and Called Upon operations, hoping to make these provisions more fair for Canada (Columbia River Treaty Review, 2011). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though both Entities’ recommendations call for modernizing the treaty, there are deep disagreements over the Canadian Entitlement and Called Upon flood protection. For the Canadian Entitlement, the US believes it is overpaying for the benefits while Canada believes it is getting its fair share. The disagreement stems from the fact that the entitlement is calculated from estimates made in the Assured Operating Plans five years in advanced. The US imposes certain limits on dams that may keep them from operating at full power in order to protect the environment (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). Therefore, the US may not be generating as much power as estimated in the AOP’s, but Canada is still entitled to half of the estimate according to the current treaty. The PEB admitted in their 2012 report that “actual U.S. power benefits from the operation of Canadian storage are unknown and can only be roughly estimated. Canadian storage has such a large impact on the operation of the U.S. system that its absence would significantly affect operating procedures, non-power requirements, loads and resources, and market conditions, thus making any benefit analysis highly speculative” (Proctor, Simms, & Robinson, 2012). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since “Called Upon” flood protection has never been used, there are disagreements over what constitutes a reasonable risk level to call it into action. The water level at The Dalles Dam in Oregon is often used as the indicator for flooding in the region. Canada believes that Called Upon can only be used with over 600kcfs of water at The Dalles, while the US believes the number to be 450kcfs. Additionally, Canada asserts that the US can only use this flood protection once the US has exhausted all of their own flood storage on the Columbia or its tributaries, while the US asserts otherwise. Lastly, there are disagreements over how the US should base its payment to Canada for lost power generated (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the US Entity sent their regional recommendations to the US Department, the indigenous tribes on the sovereign review team sent a follow-up to Secretary John Kerry. The letter supported regional recommendations and reminded the State Department of the tribes’ sovereign rights to govern their water if the State Department wants to neglect the recommendations (Bell, 2015). Ultimately, it is the federal governments, not the Entities themselves, that are negotiating the treaty renewal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Current Status=== | ||

| + | After the Entities submitted their respective recommendations in 2013, there were a couple of years without much public action. On August 11th, 2016, a group of Senators and Representatives from the Pacific Northwest led by WA Senator Maria Cantwell sent a letter to Secretary of State John Kerry to urge him to speed up the decision to go into negotiation (Cantwell, 2016). On October 7th, 2016, Senator Cantwell announced in a press release that the US was officially starting negotiations with Canada (Cantwell, U.S. Ready to Start Talks on Columbia River Treaty, 2016). Since then, little has been announced to the public regarding how (or if) negotiations are proceeding. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Moving Forward=== | ||

| + | The 1964 Columbia Treaty showcases joint fact-finding and adaptive management between the US and Canada, two traits that should continue as the treaty is renewed. The Permanent Engineering Board provides an arena for tracking the operations of the dams on both sides of the river and continually updating flood operating plans. Once the treaty is revised or renewed, the PEB should keep this role. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many concerns regarding the treaty revolve around a lack of adequate stakeholder representation. The two state departments were the negotiating parties for the original treaty and are still the negotiating parties for the current revisions. Less powerful stakeholders, such as state governments, local communities, and indigenous tribes, have been consulted for the regional recommendations. However, it is unclear how the state departments will use these recommendations. The Canadian federal government and the British Columbia governments are working closely to find a plan that works for both of them, but there is little communication between the US State Department and the Pacific Northwest States outside of the regional recommendations. Moving forward, it is important for the US State Department to directly consult states, communities, and tribes, as negotiations may shift away from the scope of the regional recommendations, which at this point were written over three years ago. It may even be possible to give these stakeholders a seat at the negotiation table, since they may have a better idea of the benefits and flaws of the treaty, based on the institutional knowledge of managing the treaty for the last fifty years. Failing to include these stakeholders can result in complicated lawsuits for the State Department (especially ones dealing with the rights of indigenous tribes), as well as a general lack of support for the new treaty. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Additionally, it is possible that the renegotiations will be held up by disagreements over the Canadian Entitlement and the Called Upon flood protections. The discussion over these issues mostly revolve just around getting the exact number (cost, water level, etc.) that everyone can agree on. There is little room for value creation within this conversation. Looking ahead, the conversation should be shifted to what the two countries can do to maximize protection and power for all. If negotiations are still held up, engaging in scenario planning can help reframe the issue to tackle the immediate flooding situation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In conclusion, the Columbia River Treaty is due for revision and renewal to accommodate for today’s pressing issues. It will be interesting to follow updates regarding this negotiation over the next several years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | (2017). Retrieved from International Joint Commission: http://www.ijc.org/en_/ | ||

| + | Bell, D. (2015). Columbia River Treaty Renewal and Sovereign. Public Land and Resources Law Review, 270-294. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cantwell, M. (2016, August 11). Dear Secretary Kerry. Retrieved from https://www.cantwell.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2016.08.11%20to%20Dept%20of%20State%20(Kerry),%20Columbia%20RIver%20Treaty.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cantwell, M. (2016, October 7). U.S. Ready to Start Talks on Columbia River Treaty. Retrieved from Maria Cantwell: https://www.cantwell.senate.gov/news/press-releases/us-ready-to-start-talks-on-columbia-river-treaty | ||

| + | |||

| + | Columbia River Treaty Review. (2011). Retrieved from British Columbia: http://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/6/2012/03/BC_Decision_on_Columbia_River_Treaty.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review. (2014, June). Retrieved from Columbia River Treaty, 2014/2024 Review: https://www.crt2014-2024review.gov/Files/Columbia%20River%20Treaty%20Review%20_revisedJune2014.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | Columbia Treaty. (1961, January 17). Washington, DC, United States of America. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Endangered Species Act. (1973, December 27). Washington, DC. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Geiling, N. (2015, February 18). How Oregon's Second Largest City Vanished in a Day. Retrieved from Smithsonian Magazine: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/vanport-oregon-how-countrys-largest-housing-project-vanished-day-180954040/ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Harrison, J. (2011, December 2). International Joint Commission. Retrieved from nwcouncil.org: https://www.nwcouncil.org/history/internationaljointcommission/ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lillis, K. (2014, June 27). The Columbia River Basin provides more than 40% of total U.S. hydroelectic generation. Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=16891 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Proctor, W. D., Simms, S. R., & Robinson, D. A. (2012). Annual Report of the Columbia River Treaty, Canada and United States Entitites. Permanent Engineering Board. Retrieved from http://www.nwd-wc.usace.army.mil/PB/PEB_08/docs/Entity/2012AnnRep.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sopinka, A., & Pitt, L. (2014). The Columbia River Treaty: Fifty Years After the Handshake. The Electricty Journal, 84-94. | ||

| + | |||

| + | U.S. Entity Regional Recommendation for the Future of the Columbia River Treaty after 2024. (2013, December). Retrieved from Columbia River Treaty, 2014/2024 Review: https://www.crt2014-2024review.gov/RegionalDraft.aspx | ||

| + | |||

| + | US EIA. (2016, November 2). Renewable Energy Explained. Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=renewable_home#tab2 | ||

| + | |Summary=Passed in 1964, the Columbia River Treaty is an agreement between the United States and Canada over the management of the Columbia River. The treaty establishes provisions for flood control and the sharing of hydropower benefits. In September of 2024, either country can terminate the treaty provided they give an advance notice of at least ten years. Both countries have been preparing to revisit this treaty and renegotiate its terms since 2013. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The original treaty was hailed as an example of effective international collaboration, with joint management by the Army Corp of Engineers and the Bonneville Power Administration on the US side and BC Hydro and Power Authority on the Canadian side. However, other stakeholders such as indigenous tribes and local communities were not included in negotiations. The creators of the 1964 treaty also did not consider the impact of dams on ecosystem services and only focused on flooding and power. The current revisiting of the treaty allows for more stakeholder involvement and expanding the treaty to include protections for the environment. Additionally, there are disagreements between the US and Canada over compensation for flood protection and the sharing of hydropower that must be resolved before the revised treaty is put in place. | ||

|Topic Tags= | |Topic Tags= | ||

|External Links= | |External Links= | ||

Latest revision as of 21:25, 1 June 2017

| Geolocation: | 48° 59' 59.4902", -117° 49' 55.267" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 77,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 670000670,000 km² 258,687 mi² km2 |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | industrial use, forest land, urban |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Fisheries - wild, Hydropower Generation |

| Water Features: | Columbia River Basin |

| Agreements: | Columbia River Treaty |

Contents

- 1 Summary

- 2 Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

- 3 Issues and Stakeholders

- 4 Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

- 5 Key Questions

Summary

Passed in 1964, the Columbia River Treaty is an agreement between the United States and Canada over the management of the Columbia River. The treaty establishes provisions for flood control and the sharing of hydropower benefits. In September of 2024, either country can terminate the treaty provided they give an advance notice of at least ten years. Both countries have been preparing to revisit this treaty and renegotiate its terms since 2013.

The original treaty was hailed as an example of effective international collaboration, with joint management by the Army Corp of Engineers and the Bonneville Power Administration on the US side and BC Hydro and Power Authority on the Canadian side. However, other stakeholders such as indigenous tribes and local communities were not included in negotiations. The creators of the 1964 treaty also did not consider the impact of dams on ecosystem services and only focused on flooding and power. The current revisiting of the treaty allows for more stakeholder involvement and expanding the treaty to include protections for the environment. Additionally, there are disagreements between the US and Canada over compensation for flood protection and the sharing of hydropower that must be resolved before the revised treaty is put in place.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

Overview

The Columbia River Treaty is a 1964 agreement between the United States of America and Canada over the management of the Columbia River. The treaty is due for renewal or termination in 2024, so both countries are currently planning for renegotiation. Issues include disagreement between the two sides over flood storage and the sharing of generated hydropower. The original treaty did not consider the environment or ecosystem services, and the revised treaty is likely to contain provisions for this topic. The state departments of the two countries are the negotiators for the treaty renewal. The US entities (Army Corp of Engineers and Bonneville Power Administration) and the Canadian entity (BC Hydro and Power Authority) who are in charge of managing the 1964 treaty have both submitted recommendations about renegotiation to their respective state departments. State governments, indigenous groups, and local communities are also impacted by the treaty renewal, but have smaller voices in the negotiations.

Geographic, Natural, and Historic Framework of the Columbia River Basin

Columbia River Basin Geography and Services

Stretching more than 1200 miles, the Columbia River is the fourth largest river in North America in terms of flow rate. The basin encompasses British Columbia in Canada and Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and little bit of California and Nevada in the United States. About 15% of the land area of the 259,000 sq. mile basin is in Canada, the upstream country, but Canadian waters account for about 38% of the average annual volume (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014).

The river provides services to both wildlife and human populations. The Columbia River is home to many species of fish (especially salmon) and their migration and reproduction cycles (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). As one of the most dammed rivers in the world, the basin provides a setting for more than 40% of total US and 92% of British Columbia hydropower generation (Lillis, 2014). In addition, the Columbia River is a source of recreation, transportation, and irrigation for the area.

Historical Background

The International Joint Commission (IJC) was formed by the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1910 to manage US-Canada transboundary waters. Its responsibilities include regulating shared water uses, investigating transboundary issues, and recommending solutions. The IJC consists of six commissioners, three appointed by the federal governments of each country, who are expected to operate independently of the countries once they are appointed. Starting in 1944, the IJC spent over a decade conducting a study on the management of the Columbia River Basin, ultimately recommending principles for sharing flood control and electric power benefits (International Joint Commission, 2017). Two major events triggered the IJC’s recommendation for a treaty: the building of the Grand Coulee Dam and the Vanport disaster.

The Grand Coulee Dam was constructed between 1933 and 1941 in Northeast Washington State by the US Bureau of Reclamation. Just before completion, the US government applied for a permit with the IJC to operate the dam, conceding that water levels may increase at the Canadian border because of this reservoir. Since the dam was mostly completed by the time the application was received, the IJC approved it with a loose promise of revisiting the issue if water levels become problematic. The building of this dam effectively eliminated many salmon and steelhead runs in the region (Harrison, 2011). Additionally, uncontrolled water flows prevented the dam from achieving its maximum efficiency (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). The Grand Coulee Dam is currently the largest electricity producing facility in the United States (US EIA, 2016).

Vanport was Oregon’s second largest city in the first half of the 1900’s. On May 30, 1948, after a snowy winter, a flood twenty-three feet tall fell upon the city. The surge of water was eight feet above the dikes that were in place, so the town was almost entirely wiped out. Approximately 18,500 residents were displaced and over a hundred people are estimated to have died. The deaths and displacement resulted from a combination of poor flood protection and assurances from the Housing Authority of Portland that the dikes would hold (Geiling, 2015).

The Grand Coulee Dam and the flooding of Vanport, Oregon caused the International Joint Commission to establish the International Columbia River Engineering Board to conduct a study to investigate different dam sites and recommend a course of action for the area. The board recommended the development of upstream storage, which would help regulate water flows and allow for better power generation and dependability at downstream dams, as well as flood protection (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). These recommendations culminated in the creation of the Columbia River Treaty.

The Columbia Treaty

Major Components of the Treaty

The Columbia Treaty was signed by representatives from the US and Canada on January 17th, 1961 and was ratified by both countries on September 16th, 1964.

The treaty tasked specific entities with implementation in their respective countries. The US entities consisted of the Northwest Division Engineer of the US Army Corp of Engineers, responsible for building and operating dams, and the administrator of the Bonneville Power Administration, a federal agency responsible for marketing the generated power. The Canadian entity consisted of the British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority (BC Hydro), responsible for managing dams and marketing power on the Canadian side. The treaty also established the Permanent Engineering Board (PEB), which is tasked with monitoring and reporting results being achieved under the treaty, as well as reconciling any technical or operation disagreements between the entities. Each country appoints two members who act independently of the countries once appointed. The US representatives are appointed by the US Secretary of the Army and the Secretary of Energy. The Canadian representatives are appointed by the Canadian federal government and the British Columbian government (Columbia Treaty, 1961).

The treaty calls for an expansion of flood storage in the basin through the building of four new dams. Canada built the Duncan Dam in 1968, Hugh Keenleyside/Arrow Dam in 1969, and the Mica Dam in 1973. The United States built the Libby Dam on the Kootenai River (a tributary of the Columbia) in 1973. These four dams effectively doubled the storage capacity of the basin (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014).

The Permanent Engineering Board was tasked with maintaining the Flood Control Operating Plan, which dictates flood and power management in the basin as a whole and is updated once a while (the most recent instance was 2003). The PEB, the US entities, and the Canadian entity are also responsible for preparing an Assured Operating Plan (AOP) for the operation of Canadian flood storage five years in advance of each operating year (Columbia Treaty, 1961).

One of the major components of the treaty is the sharing of downstream power benefits between the US and Canada. The existence of upstream Canadian dams allows for more dependable and efficient hydropower generation in the whole region. Thus, Canada is entitled to 50% of estimated downstream power benefits, as defined in each year’s AOP. This means that the US is required to sell this amount to Canada at a flat rate. The treaty defines this downstream power benefit as “the difference in the hydroelectric power capable of being generated in the United States of America with and without the use of Canadian storage, determined in advanced” (Columbia Treaty, 1961). Canada sold the initial $254 million, or about thirty-years’ worth, of power to US utility companies (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014).

The other major component of the treaty is the two types of flood protection. “Assured” flood protection is defined in each year’s AOP, which dictates how Canada should operate their storage year to year to prevent flooding in the US. The US paid Canada for sixty-years’ worth of assured flood protection in one lump sum in the 1960’s, which went to pay for Canada’s three new dams. The other type of flood protection is “Called Upon” protection, which is for emergency events. This method dictates that Canada must “when called upon by an entity designated by the United States of America for that purpose, operate within the limits of existing facilities any storage in the Columbia River basin in Canada as the entity requires to meet flood control needs for the duration of the flood control period for which the call is made” (Columbia Treaty, 1961). Called Upon flood protection has never been requested in the history of the treaty, but if it were to be requested, the US would pay Canada a flat fee for each of the first four times the provision is enacted, as well as immediately deliver power to British Columbia to compensate for the loss in power generation (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014).

The lifetime of the Columbia Treaty is sixty years. Either country can terminate this treaty after September 16th, 2024, provided that they give at least ten years’ notice. If the treaty is not terminate or revised, most provisions continue as-is. A notable exception is that “Assured” flood protection ends in 2024 regardless of treaty renewal, since the US has only paid Canada for sixty years’ worth of this protection. If the treaty is terminated, the US will no longer be required to pay the Canadian Entitlement (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). 2014 is ten years before possible termination, so both countries have been preparing to revisit the treaty.

Evaluating the Columbia Treaty

Over the last fifty years, the Columbia Treaty has shaped the landscape of water and electricity in the Pacific Northwest. The building of the Pacific Northwest-Southwest Intertie, a system of high voltage transmission lines running from British Columbia to California, has provided reliable power trading in the region. The Army Corp of Engineers, Bonneville Power Administration, and the US Bureau of Reclamation signed the Pacific Northwest Coordination Agreement, uniting most of the hydro projects in the area under one utility, optimizing operations (Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review, 2014). In addition, it is estimated that assured flood protection has saved the US over $7309.2 million between 1964 and 2005 (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014).

Despite being an example of sound transboundary cooperation, the treaty does have its flaws. First, there is a lack of environmental or ecologic provisions. The Columbia River system impacts thirteen different species of salmon and steelhead under the Endangered Species Act, which regulates the harm that the US can do to certain animals. (Endangered Species Act, 1973). Second, the creation of the new dams flooded hundreds of thousands of acres of land and displaced timber production, wildlife, farming, recreation, tourism and settlements (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). These effects are disproportionately felt by local communities and indigenous groups that rely on the river for work and play. The same stakeholders were the ones to be left out in negotiations for the 1964 treaty and will continue to be left out if negotiations are only at higher levels of governance.

The treaty renewal process has potential in fixing the issues presented here. Over the last few years, various groups have compiled recommendations on how to proceed with negotiations before 2024.

Columbia Treaty Renewal

Regional Recommendations for Treaty Renewal

In 2013, both countries’ entities published regional recommendations to their respective countries on how to proceed with negotiations. The US Entity’s recommendations, compiled by the Army Corp of Engineers and Bonneville Power Administration, called for modernizing the current treaty to meet regional needs for irrigation, municipal and industrial use, in-stream flows, navigation, and recreation, in addition to the flood and power provisions already in place. The document advocated for adaptability in the new treaty to account for climate change and new technologies, as well as minimizing adverse effects to indigenous communities. The Canadian Entitlement and Called Upon operations are currently seen as unfair by the US. These recommendations included input from a sovereign review team consisting of representatives from the four Northwest states, fifteen tribes, and the Northwest Federal Caucus, as well as consultation with regional interest groups and utility companies (U.S. Entity Regional Recommendation for the Future of the Columbia River Treaty after 2024, 2013).

The Canadian Entity’s recommendations, compiled by BC Hydro, are similar to the US’s. There is a call to modernize the treaty in order to account for climate change, navigation, water supply, and ecosystems. The Entity recommends seeking ways to maximize power benefits without impacting the environment or recreational activities. They also would like a revisit for the Canadian Entitlement and Called Upon operations, hoping to make these provisions more fair for Canada (Columbia River Treaty Review, 2011).

Though both Entities’ recommendations call for modernizing the treaty, there are deep disagreements over the Canadian Entitlement and Called Upon flood protection. For the Canadian Entitlement, the US believes it is overpaying for the benefits while Canada believes it is getting its fair share. The disagreement stems from the fact that the entitlement is calculated from estimates made in the Assured Operating Plans five years in advanced. The US imposes certain limits on dams that may keep them from operating at full power in order to protect the environment (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014). Therefore, the US may not be generating as much power as estimated in the AOP’s, but Canada is still entitled to half of the estimate according to the current treaty. The PEB admitted in their 2012 report that “actual U.S. power benefits from the operation of Canadian storage are unknown and can only be roughly estimated. Canadian storage has such a large impact on the operation of the U.S. system that its absence would significantly affect operating procedures, non-power requirements, loads and resources, and market conditions, thus making any benefit analysis highly speculative” (Proctor, Simms, & Robinson, 2012).

Since “Called Upon” flood protection has never been used, there are disagreements over what constitutes a reasonable risk level to call it into action. The water level at The Dalles Dam in Oregon is often used as the indicator for flooding in the region. Canada believes that Called Upon can only be used with over 600kcfs of water at The Dalles, while the US believes the number to be 450kcfs. Additionally, Canada asserts that the US can only use this flood protection once the US has exhausted all of their own flood storage on the Columbia or its tributaries, while the US asserts otherwise. Lastly, there are disagreements over how the US should base its payment to Canada for lost power generated (Sopinka & Pitt, 2014).

After the US Entity sent their regional recommendations to the US Department, the indigenous tribes on the sovereign review team sent a follow-up to Secretary John Kerry. The letter supported regional recommendations and reminded the State Department of the tribes’ sovereign rights to govern their water if the State Department wants to neglect the recommendations (Bell, 2015). Ultimately, it is the federal governments, not the Entities themselves, that are negotiating the treaty renewal.

Current Status

After the Entities submitted their respective recommendations in 2013, there were a couple of years without much public action. On August 11th, 2016, a group of Senators and Representatives from the Pacific Northwest led by WA Senator Maria Cantwell sent a letter to Secretary of State John Kerry to urge him to speed up the decision to go into negotiation (Cantwell, 2016). On October 7th, 2016, Senator Cantwell announced in a press release that the US was officially starting negotiations with Canada (Cantwell, U.S. Ready to Start Talks on Columbia River Treaty, 2016). Since then, little has been announced to the public regarding how (or if) negotiations are proceeding.

Moving Forward

The 1964 Columbia Treaty showcases joint fact-finding and adaptive management between the US and Canada, two traits that should continue as the treaty is renewed. The Permanent Engineering Board provides an arena for tracking the operations of the dams on both sides of the river and continually updating flood operating plans. Once the treaty is revised or renewed, the PEB should keep this role.

Many concerns regarding the treaty revolve around a lack of adequate stakeholder representation. The two state departments were the negotiating parties for the original treaty and are still the negotiating parties for the current revisions. Less powerful stakeholders, such as state governments, local communities, and indigenous tribes, have been consulted for the regional recommendations. However, it is unclear how the state departments will use these recommendations. The Canadian federal government and the British Columbia governments are working closely to find a plan that works for both of them, but there is little communication between the US State Department and the Pacific Northwest States outside of the regional recommendations. Moving forward, it is important for the US State Department to directly consult states, communities, and tribes, as negotiations may shift away from the scope of the regional recommendations, which at this point were written over three years ago. It may even be possible to give these stakeholders a seat at the negotiation table, since they may have a better idea of the benefits and flaws of the treaty, based on the institutional knowledge of managing the treaty for the last fifty years. Failing to include these stakeholders can result in complicated lawsuits for the State Department (especially ones dealing with the rights of indigenous tribes), as well as a general lack of support for the new treaty.

Additionally, it is possible that the renegotiations will be held up by disagreements over the Canadian Entitlement and the Called Upon flood protections. The discussion over these issues mostly revolve just around getting the exact number (cost, water level, etc.) that everyone can agree on. There is little room for value creation within this conversation. Looking ahead, the conversation should be shifted to what the two countries can do to maximize protection and power for all. If negotiations are still held up, engaging in scenario planning can help reframe the issue to tackle the immediate flooding situation.

In conclusion, the Columbia River Treaty is due for revision and renewal to accommodate for today’s pressing issues. It will be interesting to follow updates regarding this negotiation over the next several years.

References

(2017). Retrieved from International Joint Commission: http://www.ijc.org/en_/ Bell, D. (2015). Columbia River Treaty Renewal and Sovereign. Public Land and Resources Law Review, 270-294.

Cantwell, M. (2016, August 11). Dear Secretary Kerry. Retrieved from https://www.cantwell.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2016.08.11%20to%20Dept%20of%20State%20(Kerry),%20Columbia%20RIver%20Treaty.pdf

Cantwell, M. (2016, October 7). U.S. Ready to Start Talks on Columbia River Treaty. Retrieved from Maria Cantwell: https://www.cantwell.senate.gov/news/press-releases/us-ready-to-start-talks-on-columbia-river-treaty

Columbia River Treaty Review. (2011). Retrieved from British Columbia: http://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/6/2012/03/BC_Decision_on_Columbia_River_Treaty.pdf

Columbia River Treaty, History and 2014/2024 Review. (2014, June). Retrieved from Columbia River Treaty, 2014/2024 Review: https://www.crt2014-2024review.gov/Files/Columbia%20River%20Treaty%20Review%20_revisedJune2014.pdf

Columbia Treaty. (1961, January 17). Washington, DC, United States of America.

Endangered Species Act. (1973, December 27). Washington, DC.

Geiling, N. (2015, February 18). How Oregon's Second Largest City Vanished in a Day. Retrieved from Smithsonian Magazine: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/vanport-oregon-how-countrys-largest-housing-project-vanished-day-180954040/

Harrison, J. (2011, December 2). International Joint Commission. Retrieved from nwcouncil.org: https://www.nwcouncil.org/history/internationaljointcommission/

Lillis, K. (2014, June 27). The Columbia River Basin provides more than 40% of total U.S. hydroelectic generation. Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=16891

Proctor, W. D., Simms, S. R., & Robinson, D. A. (2012). Annual Report of the Columbia River Treaty, Canada and United States Entitites. Permanent Engineering Board. Retrieved from http://www.nwd-wc.usace.army.mil/PB/PEB_08/docs/Entity/2012AnnRep.pdf

Sopinka, A., & Pitt, L. (2014). The Columbia River Treaty: Fifty Years After the Handshake. The Electricty Journal, 84-94.

U.S. Entity Regional Recommendation for the Future of the Columbia River Treaty after 2024. (2013, December). Retrieved from Columbia River Treaty, 2014/2024 Review: https://www.crt2014-2024review.gov/RegionalDraft.aspx

US EIA. (2016, November 2). Renewable Energy Explained. Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=renewable_home#tab2

Issues and Stakeholders

Canadian Entitlement. How should Canada be compensated for power benefits from downstream power generation?

NSPD: Governance, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency

Water storage in British Columbia allows for more predictability and control over the entire Columbia River Basin, thus hydropower facilities in the US Pacific Northwest can produce power more efficiently. The treaty requires the US to sell 50% of the estimated downstream power generated to Canada at a fixed cost. In revisiting this treaty, the US feels it is allotting too much power to Canada, while Canada feels like the share is justified and could be higher.

Stakeholders

- US State Department

- Canadian State Department

- US Army Corp of Engineers

- Bonneville Power Administration, US federal power authority stationed in Oregon

- BC Hydro and Power Authority, British Columbia’s public power authority

- Other electricity companies

Flood Protection. How should flood storage be operated so that the basin is protected from flooding without a large disruption to business-as-usual operations?

NSPD: Water Quantity, Ecosystems, Governance

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency

The Columbia River Treaty defines two types of flood protection that Canada provides to the US, “Assured” for day-to-day operations and “Called Upon” for emergencies. The treaty only guarantees assured flood protection until 2024, even if the treaty itself is not terminated. Called Upon flood storage will be the only measure if the treaty is not revised. The US and Canada disagree on when it is appropriate to call upon this measure.

Stakeholders

- US State Department

- Canadian State Department

- US Army Corp of Engineers

- Bonneville Power Administration, US federal power authority stationed in Oregon

- BC Hydro and Power Authority, British Columbia’s public power authority

- Communities along the river

Ecosystem Services. How can the US and Canadian entities ensure minimum damage to fish and surrounding ecosystems in the basin?

NSPD: Ecosystems, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Local Government, Environmental interest, Community or organized citizens

The 1964 treaty only covers power and flood related issues and ignores environmental and ecosystem issues. Dams have killed off many salmon and steelhead populations. The new treaty should include clauses on protecting the ecosystem and revitalizing fish populations.

Stakeholders

- US State Department

- Canadian State Department

- US Army Corp of Engineers

- Bonneville Power Administration, US federal power authority stationed in Oregon

- BC Hydro and Power Authority, British Columbia’s public power authority

- First Nations and Indigenous Communities

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreNo ASI articles have been added yet for this case

Key Questions

Hydropower Dams and Large Storage Infrastructure: Where does the benefit “flow” from a hydropower project and how does that affect implementation and sustainability of the project?

no description entered

Transboundary Water Issues: What kinds of water treaties or agreements between countries can provide sufficient structure and stability to ensure enforceability but also be flexible and adaptable given future uncertainties?

no description entered

Transboundary Water Issues: What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution?

no description entered