Difference between revisions of "Transboundary Dispute Resolution: U.S./Mexico Shared Aquifers"

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

m (Saved using "Save and continue" button in form) |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

}} | }} | ||

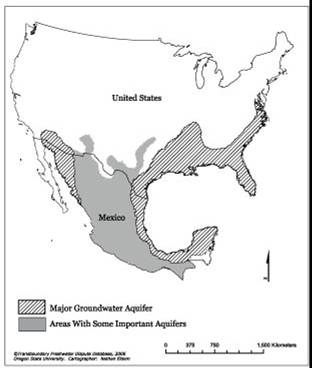

|REP Framework=[[File:US_Mexico_Aquifers.jpg]] Image 1. Map of shared (transboundary) aquifers between Mexico and U.S<ref name = "TFDD 2012">Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/US_Mexico_Aquifer_New.htm </ref> | |REP Framework=[[File:US_Mexico_Aquifers.jpg]] Image 1. Map of shared (transboundary) aquifers between Mexico and U.S<ref name = "TFDD 2012">Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/US_Mexico_Aquifer_New.htm </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| Line 28: | Line 29: | ||

The complications of groundwater are exemplified in the border region between the United States and Mexico where, despite the presence of an active supra-legal authority since 1944, groundwater issues have yet to be resolved. Mentioned as vital in the [[1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty|1944 Treaty]], and again in 1973, the difficulties in quantifying the ambiguities inherent in groundwater regimes has eluded legal and management experts ever since. | The complications of groundwater are exemplified in the border region between the United States and Mexico where, despite the presence of an active supra-legal authority since 1944, groundwater issues have yet to be resolved. Mentioned as vital in the [[1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty|1944 Treaty]], and again in 1973, the difficulties in quantifying the ambiguities inherent in groundwater regimes has eluded legal and management experts ever since. | ||

| + | As talks persist between both major stakeholders current data suggests that the aquifers on the US/Mexico border are being overused and becoming less sustainable every day. “rapid population growth, increasing water demand and the declining quality of water resources contribute to significant water and water infrastructure needs” <ref name="Austin 2012">Austin, Diane. United States . Good Neighbor Environmental Board. Environmental, Economic, and Health Status of Water Resources in the U.S.-Mexico Border Region. 2012. Print. available online http://www.epa.gov/ofacmo/gneb/gneb15threport/English-GNEB-15th-Report.pdf </ref> | ||

| + | Gabriel Eckstein, Director of the International Water Law Project and Professor of Law at Texas Wesleyan University states “neither Mexico nor the United States seem inclined to pursue a border-wide pact to coordinate management of these critical freshwater resources. While recommendations have been proffered for more than forty years, all appear to have fallen on deaf ears. As a result, these resources are now being overexploited on both frontiers as populations and industries pump with little regard for sustainability or transboundary consequences. Moreover, these subsurface reservoirs are being fouled by untreated wastes, agricultural and industrial by-products, and other sources of pollution. Imminently unsustainable, the situation portends a grim future for the region” <ref name="Eckstein 5-2013"> Eckstein, Gabriel. "Rethinking Transboundary Groundwater Resource Management: A local approach along the Mexico-U.S. Border." Archive for the ‘Mexico-US Border’ Category. International Water Law Project, 06 May 2013. Web. 30 Jul. 2013. http://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/blog/category/mexico-us-border/ </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | “No two aquifers are alike; each functions as a complex and unique hydrological system. Moreover, no two aquifers are perceived equally by overlaying communities, especially where those communities are highly dependent on the resources to meet their daily freshwater needs. Hence, aquifers traversing the Mexico-U.S. border cannot be managed effectively through a single, comprehensive, border-wide treaty. While a border-wide scheme may be politically convenient, such an approach could only offer very general guidelines and standards, and may prove detrimental to the sustainable management of some of the region’s subsurface waters” <ref name="Eckstein 5-2013"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Surface water resources were developed and institutional arrangements established to manage those resources before ground water resources were developed and governed, so there are few policies and institutions in place to govern ground water resources. The combined effects of inadequate infrastructure, lack of financial resources and gaps in authority, along with the need to share water supply during times of drought, present substantial challenges and require comprehensive solutions” <ref name="Austin 2012" /> If the two states are unable to reach a comprehensive and efficient agreement then the aquifers in the region will continue on this path to becoming unsustainable which will not only cause many deaths in the region but will destroy the economy in the region that both states are heavily reliant on. | ||

== Attempts at Conflict Management == | == Attempts at Conflict Management == | ||

| Line 35: | Line 42: | ||

Mumme states that there are three main reasons why Minute 242 has had trouble being advanced as its agreement intended.<ref name="Mumme 2004"/> First, and maybe most importantly, was that there was not the political support to carry out Minute 242. A rift between state and federal government over whose authority it was to control water rights played a key role and when there are 96 seats in the House of Representatives from the border region, this makes it difficult to pass any legislation going against those states. Secondly, it is possible that Minute 242 did not refer to groundwater quality in general, but more pointedly at salinity. This may have averted governments from pursuing appropriate studies. And third, the terms of reference of both Minute 242 and the [[1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty|1944 Treaty]] are not very clear. The wording of the agreements does not have enough definition to promote decisive acts and leaves much to be questioned. | Mumme states that there are three main reasons why Minute 242 has had trouble being advanced as its agreement intended.<ref name="Mumme 2004"/> First, and maybe most importantly, was that there was not the political support to carry out Minute 242. A rift between state and federal government over whose authority it was to control water rights played a key role and when there are 96 seats in the House of Representatives from the border region, this makes it difficult to pass any legislation going against those states. Secondly, it is possible that Minute 242 did not refer to groundwater quality in general, but more pointedly at salinity. This may have averted governments from pursuing appropriate studies. And third, the terms of reference of both Minute 242 and the [[1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty|1944 Treaty]] are not very clear. The wording of the agreements does not have enough definition to promote decisive acts and leaves much to be questioned. | ||

| − | In 2006, the [[U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Act |U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Act]] was passed, which mandated the creation of a scientific program to inventory, map, and create hydrological models for aquifers along the U.S.-Mexico border. The act allows the secretary of the interior to work with the [[IBWC]] and states bordering Mexico developing projects which focus on "priority transboundary aquifers". | + | In 2006, the [[U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Act |U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Act]] was passed, which mandated the creation of a scientific program to inventory, map, and create hydrological models for aquifers along the U.S.-Mexico border. The act allows the secretary of the interior to work with the [[IBWC]] and states bordering Mexico developing projects which focus on "priority transboundary aquifers". |

| + | |||

| + | == Treaties/Agreements == | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1906: The treaty signed at the Convention of 1906 governed the international reach of the river between El Paso, Texas-Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua and Fort Quitman, Texas. The treaty provided for the United States to deliver to Mexico 60,000 acre-feet per year of Rio Grande water for agricultural use. The allocation is reduced in the event of extraordinary drought. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1922: The Colorado River Compact of 1922 defined the relationship between the Upper Basin states, where most of the river’s water supply originates, and the Lower Basin states, and allocated 7.5 million acre-feet to each basin. The Boulder Canyon Project Act apportioned the Lower Basin’s allocation among the States of Arizona, California and Nevada. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1933: The Convention of 1933 governed the joint construction, operation and maintenance (O&M) of the Rio Grande Rectification Project, which straightened, stabilized and shortened the river boundary in this area. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1938: The Rio Grande Compact was signed in 1938 and apportioned the waters of the Rio Grande above Fort Quitman, Texas, among Colorado, New Mexico and Texas. The Rio Grande Compact Commission establishes water delivery obligations and depletion entitlements for Colorado and New Mexico. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1944: The Water Treaty of 1944 allocated the waters of the Colorado and Rio Grande Rivers between the two countries; provided for the construction of reclamation works on the main channel of the international reach of the Rio Grande; allowed the newly created IBWC to give preferential attention to the solution of border sanitation problems; and provided the IBWC with authority to apply and interpret the terms of the Treaty with the consent of the two governments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1948: The 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact created the Upper Colorado River Commission and apportioned the Upper Basin’s allocation among Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and the portion of Arizona that lies within the Upper Colorado Basin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1973: Minute 242 on groundwater signed between Mexico and the United States. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1983: La Paz Agreement signed creating technical working groups that addressed water quality among other environmental concerns. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1991: The New Mexico-Texas Water Commission is formed | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1992-1994: Integrated Border Environmental Plan implemented | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1993: North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) signed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1994: NAFTA implemented. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1996-2000: Border XXI program (a collaborative effort of EPA, USDA, U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Health and Human Services, Mexico’s Secretariat of Environment, Natural Resources and Fisheries [SEMARNAP] and Secretariat of Health, and the U.S. and Mexican Sections of the IBWC). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2007: the Secretary of the Interior adopted guidelines to reduce allocations if Lake Mead reaches critically low elevations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2012: Border 2012 was created from the 1996 border program. Water quality was a main focus of the Border 2012 program and was addressed through the Water Policy Forum, Border 2012 goals were to reduce water contamination and border infrastructure projects. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2020: Border 2020 (the successor to Border 2012) will build on the prior programs with one of five central goals being to improve water quality and water infrastructure sustainability, and reduce exposure to contaminated water. | ||

| + | |||

== Outcome == | == Outcome == | ||

| Line 41: | Line 83: | ||

Even after three decades of having problems with Minute 242 and groundwater issues, there does not appear to be a movement towards a new agreement referring to the United States-Mexican shared aquifers anytime soon, although Mumme states that it is likely that "some form of systematic cooperation will emerge" between stakeholders in more local areas along the border.<ref name="Mumme 2004" /> | Even after three decades of having problems with Minute 242 and groundwater issues, there does not appear to be a movement towards a new agreement referring to the United States-Mexican shared aquifers anytime soon, although Mumme states that it is likely that "some form of systematic cooperation will emerge" between stakeholders in more local areas along the border.<ref name="Mumme 2004" /> | ||

| + | “Presently, there exists no comprehensive agreement between Mexico and the United States on the regulation, management, allocation, or protection of the numerous aquifers straddling the border-region. This absence, however, does not mean that there is no law on the border pertaining to ground water resources. In fact, there are numerous sources of law that, to varying degrees, are relevant to these border resources. This multiplicity of legal regimes and jurisdictions, however, is one of the most vexing challenges to the development of robust bi-national cooperation” <ref name="Eckstein 2011">Eckstein, Gabriel. "Buried Treasure or Buried Hope? The Status of Mexico-U.S. Transboundary Aquifers under International Law." International Community Law Review. (2011): 273-290. Web. 30 Jul. 2013. http://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/bibliography/articles/Eckstein-Mex-US_ICLR.pdf </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Regardless of the lack of legislation there are numerous agencies on both sides working on data analysis and legislation for transboundary aquifers. Many are also focusing on water purification, sustainability, other plans that are to be implemented in the future. Although their is no formal plan yet, progress is being made to make the transboundary aquifers sustainable and the region less impoverished. | ||

The Arizona-Sonora Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Program is one of at least two programs started as a result of the [[U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Act |TAAA]]. It is based out of the University of Arizona, and coordinates with stakeholders in the U.S. and Mexico to monitor and assess the San Pedro and Santa Cruz aquifers. | The Arizona-Sonora Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Program is one of at least two programs started as a result of the [[U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Act |TAAA]]. It is based out of the University of Arizona, and coordinates with stakeholders in the U.S. and Mexico to monitor and assess the San Pedro and Santa Cruz aquifers. | ||

|Issues={{Issue | |Issues={{Issue | ||

| Line 50: | Line 95: | ||

* Mexico | * Mexico | ||

* [[IBWC|International Boundary and Water Commission]] ([[IBWC]][[IBWC|International Boundary and Water Commission]]) | * [[IBWC|International Boundary and Water Commission]] ([[IBWC]][[IBWC|International Boundary and Water Commission]]) | ||

| + | *United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) | ||

| + | *

Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) | ||

| + | *Good Neighbor Environmental Board (GNEB)

| ||

| + | *New Mexico Water Resources Research Institute (NMWRRI)

| ||

| + | *Estados Unidos Mexicanos Comisión Internacional de Limites y Aguas (CILA)

| ||

| + | *Comisión Nacional del Agua (CNA)

| ||

| + | *Junta Municipal de Agua y Saneamiento de Ciudad Juárez (JMAS) | ||

|NSPD=Water Quantity; Water Quality; Governance; Assets | |NSPD=Water Quantity; Water Quality; Governance; Assets | ||

| − | |Stakeholder Type=Sovereign state/national/federal government, Supranational union | + | |Stakeholder Type=Sovereign state/national/federal government, Supranational union, Environmental interest |

}} | }} | ||

|Key Questions={{Key Question | |Key Questions={{Key Question | ||

Revision as of 12:20, 31 July 2013

| Geolocation: | 31° 46' 12.7463", -106° 29' 45.497" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 22,874,80022,874,800,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 1,310,6301,310,630 km² 506,034.243 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type), Arid/desert (Köppen B-type), Humid mid-latitude (Köppen C-type), Dry-summer, Dry-winter |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, rangeland, urban |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Recreation or Tourism |

| Water Projects: | IBWC |

| Agreements: | 1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty, The Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Act |

Contents

Summary

The border region between the United States and Mexico has fostered its share of surface-water conflict, from the Colorado River to the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo River. It has also been a model for peaceful conflict resolution, notably the work of the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), the supra-legal body established to manage shared water resources as a consequence of the 1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty. Yet the difficulties encountered in managing shared surface-water pale in comparison to trying to allocate groundwater resources-each aquifer system is generally not understood as gathering information on aquifers is very costly and the science of groundwater is still inexact. This makes negotiations over a shared aquifer system very difficult. The complications of groundwater are exemplified in the border region between the United States and Mexico where, despite the presence of an active supra-legal authority since 1944, groundwater issues have yet to be resolved. Mentioned as vital in the 1944 Treaty, and again in 1973, the difficulties in quantifying the ambiguities inherent in groundwater regimes has eluded legal and management experts ever since. Even after three decades of having problems with the 1944 Treaty and groundwater issues, there does not appear to be a movement towards a new agreement referring to the United States-Mexican shared aquifers anytime soon, although Mumme[1] states that it is likely that "some form of systematic cooperation will emerge" between stakeholders in more local areas along the border.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

Image 1. Map of shared (transboundary) aquifers between Mexico and U.S[2]

Image 1. Map of shared (transboundary) aquifers between Mexico and U.S[2]

Background

The border region between the United States and Mexico has fostered its share of surface-water conflict, from the Colorado River to the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo River. It has also been a model for peaceful conflict resolution, notably the work of the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), the supra-legal body established to manage shared water resources as a consequence of the 1944 US-Mexico Water Treaty. Yet the difficulties encountered in managing shared surface-water pale in comparison to trying to allocate groundwater resources-each aquifer system is generally not understood as gathering information on aquifers is very costly and the science of groundwater is still inexact. This makes negotiations over a shared aquifer system very difficult.

In a 1988 Center for U.S. - Mexican Studies Report, Mumme identified 23 sites in contention in six different hydrogeologic regions along the 3,300 kilometers of shared boundary.[3] While the 1944 Treaty mentions the importance of resolving the allocations of groundwater between the two states, it does not do so. In fact, shared surface-water resources were the focus of the IBWC until the early 1960s, when a U.S. irrigation district began draining saline groundwater into the Colorado River and deducting the quantity of saline water from Mexico 's share of freshwater. In response, Mexico began a "crash program" of groundwater development in the border region, to make up the losses.

The Problem

The complications of groundwater are exemplified in the border region between the United States and Mexico where, despite the presence of an active supra-legal authority since 1944, groundwater issues have yet to be resolved. Mentioned as vital in the 1944 Treaty, and again in 1973, the difficulties in quantifying the ambiguities inherent in groundwater regimes has eluded legal and management experts ever since. As talks persist between both major stakeholders current data suggests that the aquifers on the US/Mexico border are being overused and becoming less sustainable every day. “rapid population growth, increasing water demand and the declining quality of water resources contribute to significant water and water infrastructure needs” [4]

Gabriel Eckstein, Director of the International Water Law Project and Professor of Law at Texas Wesleyan University states “neither Mexico nor the United States seem inclined to pursue a border-wide pact to coordinate management of these critical freshwater resources. While recommendations have been proffered for more than forty years, all appear to have fallen on deaf ears. As a result, these resources are now being overexploited on both frontiers as populations and industries pump with little regard for sustainability or transboundary consequences. Moreover, these subsurface reservoirs are being fouled by untreated wastes, agricultural and industrial by-products, and other sources of pollution. Imminently unsustainable, the situation portends a grim future for the region” [5]

“No two aquifers are alike; each functions as a complex and unique hydrological system. Moreover, no two aquifers are perceived equally by overlaying communities, especially where those communities are highly dependent on the resources to meet their daily freshwater needs. Hence, aquifers traversing the Mexico-U.S. border cannot be managed effectively through a single, comprehensive, border-wide treaty. While a border-wide scheme may be politically convenient, such an approach could only offer very general guidelines and standards, and may prove detrimental to the sustainable management of some of the region’s subsurface waters” [5]

“Surface water resources were developed and institutional arrangements established to manage those resources before ground water resources were developed and governed, so there are few policies and institutions in place to govern ground water resources. The combined effects of inadequate infrastructure, lack of financial resources and gaps in authority, along with the need to share water supply during times of drought, present substantial challenges and require comprehensive solutions” [4] If the two states are unable to reach a comprehensive and efficient agreement then the aquifers in the region will continue on this path to becoming unsustainable which will not only cause many deaths in the region but will destroy the economy in the region that both states are heavily reliant on.

Attempts at Conflict Management

Ten years of negotiations resulted in a 1973 addendum to the 1944 Treaty-Minute 242 of the IBWC, which limited groundwater withdrawals on both sides of the border, and committed each nation to consult the other regarding any future groundwater development. In all of the Minutes added to the 1944 Treaty since its inception, Minute 242 is still the only agreement between the two nations with regards to groundwater pumping.

Mumme states that there are three main reasons why Minute 242 has had trouble being advanced as its agreement intended.[1] First, and maybe most importantly, was that there was not the political support to carry out Minute 242. A rift between state and federal government over whose authority it was to control water rights played a key role and when there are 96 seats in the House of Representatives from the border region, this makes it difficult to pass any legislation going against those states. Secondly, it is possible that Minute 242 did not refer to groundwater quality in general, but more pointedly at salinity. This may have averted governments from pursuing appropriate studies. And third, the terms of reference of both Minute 242 and the 1944 Treaty are not very clear. The wording of the agreements does not have enough definition to promote decisive acts and leaves much to be questioned.

In 2006, the U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Act was passed, which mandated the creation of a scientific program to inventory, map, and create hydrological models for aquifers along the U.S.-Mexico border. The act allows the secretary of the interior to work with the IBWC and states bordering Mexico developing projects which focus on "priority transboundary aquifers".

Treaties/Agreements

1906: The treaty signed at the Convention of 1906 governed the international reach of the river between El Paso, Texas-Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua and Fort Quitman, Texas. The treaty provided for the United States to deliver to Mexico 60,000 acre-feet per year of Rio Grande water for agricultural use. The allocation is reduced in the event of extraordinary drought.

1922: The Colorado River Compact of 1922 defined the relationship between the Upper Basin states, where most of the river’s water supply originates, and the Lower Basin states, and allocated 7.5 million acre-feet to each basin. The Boulder Canyon Project Act apportioned the Lower Basin’s allocation among the States of Arizona, California and Nevada.

1933: The Convention of 1933 governed the joint construction, operation and maintenance (O&M) of the Rio Grande Rectification Project, which straightened, stabilized and shortened the river boundary in this area.

1938: The Rio Grande Compact was signed in 1938 and apportioned the waters of the Rio Grande above Fort Quitman, Texas, among Colorado, New Mexico and Texas. The Rio Grande Compact Commission establishes water delivery obligations and depletion entitlements for Colorado and New Mexico.

1944: The Water Treaty of 1944 allocated the waters of the Colorado and Rio Grande Rivers between the two countries; provided for the construction of reclamation works on the main channel of the international reach of the Rio Grande; allowed the newly created IBWC to give preferential attention to the solution of border sanitation problems; and provided the IBWC with authority to apply and interpret the terms of the Treaty with the consent of the two governments.

1948: The 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact created the Upper Colorado River Commission and apportioned the Upper Basin’s allocation among Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and the portion of Arizona that lies within the Upper Colorado Basin.

1973: Minute 242 on groundwater signed between Mexico and the United States.

1983: La Paz Agreement signed creating technical working groups that addressed water quality among other environmental concerns.

1991: The New Mexico-Texas Water Commission is formed

1992-1994: Integrated Border Environmental Plan implemented

1993: North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) signed.

1994: NAFTA implemented.

1996-2000: Border XXI program (a collaborative effort of EPA, USDA, U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Health and Human Services, Mexico’s Secretariat of Environment, Natural Resources and Fisheries [SEMARNAP] and Secretariat of Health, and the U.S. and Mexican Sections of the IBWC).

2007: the Secretary of the Interior adopted guidelines to reduce allocations if Lake Mead reaches critically low elevations.

2012: Border 2012 was created from the 1996 border program. Water quality was a main focus of the Border 2012 program and was addressed through the Water Policy Forum, Border 2012 goals were to reduce water contamination and border infrastructure projects.

2020: Border 2020 (the successor to Border 2012) will build on the prior programs with one of five central goals being to improve water quality and water infrastructure sustainability, and reduce exposure to contaminated water.

Outcome

Even after three decades of having problems with Minute 242 and groundwater issues, there does not appear to be a movement towards a new agreement referring to the United States-Mexican shared aquifers anytime soon, although Mumme states that it is likely that "some form of systematic cooperation will emerge" between stakeholders in more local areas along the border.[1]

“Presently, there exists no comprehensive agreement between Mexico and the United States on the regulation, management, allocation, or protection of the numerous aquifers straddling the border-region. This absence, however, does not mean that there is no law on the border pertaining to ground water resources. In fact, there are numerous sources of law that, to varying degrees, are relevant to these border resources. This multiplicity of legal regimes and jurisdictions, however, is one of the most vexing challenges to the development of robust bi-national cooperation” [6]

Regardless of the lack of legislation there are numerous agencies on both sides working on data analysis and legislation for transboundary aquifers. Many are also focusing on water purification, sustainability, other plans that are to be implemented in the future. Although their is no formal plan yet, progress is being made to make the transboundary aquifers sustainable and the region less impoverished. The Arizona-Sonora Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Program is one of at least two programs started as a result of the TAAA. It is based out of the University of Arizona, and coordinates with stakeholders in the U.S. and Mexico to monitor and assess the San Pedro and Santa Cruz aquifers.

Issues and Stakeholders

Developing an equitable apportionment of shared aquifers between the United States and Mexico.

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Governance, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Supranational union, Environmental interest

The complications of groundwater are exemplified in the border region between the United States and Mexico where, despite the presence of an active supra-legal authority since 1944, groundwater issues have yet to be resolved.

Stakeholders:

- United States of America

- Mexico

- International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWCInternational Boundary and Water Commission)

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA)

- Texas Water Development Board (TWDB)

- Good Neighbor Environmental Board (GNEB)

- New Mexico Water Resources Research Institute (NMWRRI)

- Estados Unidos Mexicanos Comisión Internacional de Limites y Aguas (CILA)

- Comisión Nacional del Agua (CNA)

- Junta Municipal de Agua y Saneamiento de Ciudad Juárez (JMAS)

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreContributed by: Aaron T. Wolf, Joshua T. Newton, Matthew Pritchard (last edit: 12 February 2013)

Key Questions

Transboundary Water Issues: What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution?

Even if conditions for agreement are good, this does not guarantee that issues will be resolved. It is testimony to the complexity of international groundwater regimes that despite the presence of an active authority for cooperative management, and despite relatively warm political relations and few riparians, negotiations have continued since 1973 without resolution.

Because uncertainty has played such a large role in influencing user behavior and thus the overexploitation of these transboundary aquifers, it is clear that institutions capable of collecting bias-free data on hydrologic parameters of water resources, and distributing this information to stakeholder on boh sides of the border, should be an integral part of future transboundary water agreements.

External Links

- Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) (2012). Oregon State University. U.S./Mexico Shared Aquifers — The Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) This website is used to aid in the assessment of the process of water conflict prevention and resolution. Over the years we have developed this Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, a project of the Oregon State University Department of Geosciences, in collaboration with the Northwest Alliance for Computational Science and Engineering.

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Mumme, S. (2004). Advancing binational cooperation in the transboundary aquifer management on the U.S.-Mexico Border. Paper presented at Groundwater in the West Conference, University of Colorado at Boulder.

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/US_Mexico_Aquifer_New.htm

- ^ Mumme, S. 1988. "Apportioning Groundwater Beneath the U.S.- Mexico Border: Obstacles and Alternatives." Center for U.S.- Mexican Studies Report Series 45.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Austin, Diane. United States . Good Neighbor Environmental Board. Environmental, Economic, and Health Status of Water Resources in the U.S.-Mexico Border Region. 2012. Print. available online http://www.epa.gov/ofacmo/gneb/gneb15threport/English-GNEB-15th-Report.pdf

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Eckstein, Gabriel. "Rethinking Transboundary Groundwater Resource Management: A local approach along the Mexico-U.S. Border." Archive for the ‘Mexico-US Border’ Category. International Water Law Project, 06 May 2013. Web. 30 Jul. 2013. http://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/blog/category/mexico-us-border/

- ^ Eckstein, Gabriel. "Buried Treasure or Buried Hope? The Status of Mexico-U.S. Transboundary Aquifers under International Law." International Community Law Review. (2011): 273-290. Web. 30 Jul. 2013. http://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/bibliography/articles/Eckstein-Mex-US_ICLR.pdf