Difference between revisions of "Water Quality Control of the South-to-North Water Diversion (SNWD) Middle Route Project (MRP)"

| [unchecked revision] | [checked revision] |

(Created page with "{{Case Study |Geolocation=32.6, 111.6 |Population=11.98 |Area=95000 |Climate=temperate |Land Use=agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban |Water Use=Agricultu...") |

|||

| (100 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

|Land Use=agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban | |Land Use=agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban | ||

|Water Use=Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Industry - consumptive use, Industry - non-consumptive use | |Water Use=Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Industry - consumptive use, Industry - non-consumptive use | ||

| − | |Key Questions= | + | |Water Feature={{Link Water Feature |

| − | | | + | |Water Feature=Han River (Yangtze River) |

| − | |Analysis and Synthesis= | + | }}{{Link Water Feature |

| + | |Water Feature=Danjiangkou Reservoir | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |Riparian={{Link Riparian | ||

| + | |Riparian=China | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |Water Project={{Link Water Project | ||

| + | |Water Project=South-North Water Transfer Project | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |Agreement= | ||

| + | |REP Framework===Introduction== | ||

| + | China has low water availability, with per capita annually renewable water resources of about one quarter of the global average <ref name="World Bank 2002"> World Bank. (2002).World Development Indicators 2002. Retrieved from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2002/10/12/000094946_0210120412542/Rendered/PDF/multi0page.pdf</ref>. The problem of low per capita water availability is exacerbated by the fact that the spatial distribution of water resources does not match the distribution of population and industry <ref name=" Zhang 2009"> Zhang, Q. (2009). The South-to-North Water Transfer Project of China: Environmental Implications and Monitoring Strategy. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 45(5), 1238–1247. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2009.00357.x</ref>. The majority of precipitation and surface water is located in the South, while water demands are much higher in the North due to the greater agricultural production and as well as the populous, industrialized cities <ref name=" Zhang 2009"> Zhang, Q. (2009). The South-to-North Water Transfer Project of China: Environmental Implications and Monitoring Strategy. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 45(5), 1238–1247. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2009.00357.x</ref>. In the North (the Hai, Huai, and Huang (Yellow River) watersheds) per capita annual water resources are just ranges from 225 to 656 m3 across the watersheds while in the South, in the Yangtze River watershed, per capita water availability is 2,100 m3 <ref name=" Varis & Vakkilainen 2001"> Varis, O., & Vakkilainen, P. (2001). China’s 8 challenges to water resources management in the first quarter of the 21st Century. Geomorphology, 41(2-3), 93–104. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(01)00107-6</ref> <ref name=" Shao, Wang & Wang 2003"> Shao, X., Wang, H., & Wang, Z. (2003). International Journal of River Basin Management Interbasin transfer projects and their implications : A China case study. International Journal of River Basin Management, 1(1), 37–41.</ref>. Water availability across the Northern region, is below the United Nations threshold for water scarcity of 1,000 m3 per capita <ref name=" UNDESA 2013"> United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2013). International Decade for Action ‘Water for Life’ 2005-2015: Water Scarcity. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The idea of transferring water from the South the North first arose in the early 1950’s. The late Chairman Mao suggested “borrowing” water from the South to meet the demands of the North <ref name="Yang & Zehnder 2005"> Yang, H., & Zehnder, A. J. B. (2005). The South-North Water Transfer Project in China The South-North Water Transfer Project in China An Analysis of Water Demand Uncertainty and Environmental, (February 2013), 37–41.</ref>. The concept was ambitious. The scheme involved transferring water over 1,000 km which would require a huge investment in capital and require overcoming significant engineering challenges <ref name="Yang & Zehnder 2005"> Yang, H., & Zehnder, A. J. B. (2005). The South-North Water Transfer Project in China The South-North Water Transfer Project in China An Analysis of Water Demand Uncertainty and Environmental, (February 2013), 37–41.</ref>. Over the next several decades, scientists and engineers debated the technical and economic feasibility of Mao’s vision. Engineering studies of the proposed transfer began in the 1950’s at which time three alignments were described: the Eastern Route, the Middle Route, and the Western Route (Figure 1)<ref name=" Berkoff 2003"> Berkoff, J. (2003). China : The South – North Water Transfer Project — is it justified ? Water Policy, 5, 1–28.</ref>. The Eastern Route diverts water from the Yangtze approximately 100 km below Nanjing and transfers it North to Tianjin; the Middle Route extracts water from the Danjiangkou Reservoir (Figure 2) on the Han River, a tributary to the Yangtze and diverts it to Beijing; the Western Route diverts water from the upper Yangtze tributaries to the arid Northwestern region <ref name=" Berkoff 2003"> Berkoff, J. (2003). China : The South – North Water Transfer Project — is it justified ? Water Policy, 5, 1–28.</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In 2002, the South-to-North Water Division Project (SNWDP) was approved and construction began on the Eastern Route <ref name="Zhang et al. 2009"> Zhang, Q., Xu, Z., Shen, Z., Li, S., & Wang, S. (2009). The Han River watershed management initiative for the South-to-North Water Transfer project (Middle Route) of China. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 148(1-4), 369–77. doi:10.1007/s10661-008-0167-z.</ref>. Construction has since begun on the Middle Route but has not yet begun on the Western Route. The government plans to complete construction of the Eastern and Middle Routes by 2013 and 2014 respectively <ref name="Wong 2011"> Wong, E. (2011, June 1). Plan for China’s Water Crisis Spurs Concern. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/02/world/asia/02water.html?pagewanted=all.</ref>. As the construction of the projects proceeds, one question arises: what will the water quality of water delivered to the north be? According to the plans, water in the Danjiangkou Reservoir, the water source for the Middle Route, should exceed the Chinese Surface Water Standard for class II water <ref name=" Dong & Wang 2011"> Dong, Z., & Wang, J. (2011). Quantitative standard of eco-compensation for the water source area in the middle route of the South-to-North Water Transfer Project in China. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering in China, 5(3), 459–473. doi:10.1007/s11783-010-0288-9</ref>. Poor water quality would increase treatment cost. Water quality can be improved and controlled through watershed protection measures in the South; however, this has both direct and indirect costs for communities in the South <ref name=" Dong & Wang 2011"> Dong, Z., & Wang, J. (2011). Quantitative standard of eco-compensation for the water source area in the middle route of the South-to-North Water Transfer Project in China. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering in China, 5(3), 459–473. doi:10.1007/s11783-010-0288-9</ref>. The majority of the focus on water quality has been on the Middle Route which when complete will be the largest water transfer in the world; within the Middle Route watershed, Shiyan City has been the focus of watershed protection schemes because it is the largest city located in the Danjiangkou Reservoir source protection area and has the longest reservoir shoreline <ref name=" Dong et al. 2011"> Dong, Z., Yan, Y., Duan, J., Fu, X., Zhou, Q., Huang, X., Zhu, X., et al. (2011). Computing payment for ecosystem services in watersheds: An analysis of the Middle Route Project of South-to-North Water Diversion in China. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 23(12), 2005–2012. doi:10.1016/S1001-0742(10)60663-8</ref>. Planned watershed protection actions require capital investments and restrict development options for Shiyan City and the surrounding area. For this reason, the receiving area, the North, is expected to compensate the source area for their conservation efforts. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) has been implemented in China before but criteria for fair compensation is not clear <ref name=" Dong et al. 2011"> Dong, Z., Yan, Y., Duan, J., Fu, X., Zhou, Q., Huang, X., Zhu, X., et al. (2011). Computing payment for ecosystem services in watersheds: An analysis of the Middle Route Project of South-to-North Water Diversion in China. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 23(12), 2005–2012. doi:10.1016/S1001-0742(10)60663-8</ref>. This case study will focus on the water quality control in Middle Route source area and the use of PES to compensate the source area residents for their direct and indirect costs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{#tag:gallery| | ||

| + | |||

| + | File:River_project_watershed_Zhang2009.jpg {{!}} Figure 1: Map of the Middle Route Project and Han River Watershed. See file for source information. | ||

| + | File:Satellite of MRP region.jpg {{!}} Figure 2: Satellite Image of Danjiangkou Reservoir | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Governance Framework== | ||

| + | To understand the political framework of the topic of interest, we need to first take a look at the political framework of Chinese government system, as shown in Figure 3. The top administrative organization is called the State Council, followed hierarchically by provinces and Municipalities, cities, counties or districts, and villages. There are also Autonomous Regions (e.g. Xinjiang and Tibet), as well as Special Administrative Regions (e.g. Hongkong and Macau), which are at the same level as provinces. Ministries, such as Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Water Resources, etc., are executive bodies under the direct lead of the State Council. Departments of similar functions (environmental protection, water resources, etc.) take responsibility at the provincial, city, and even district level; they report to their superior organizations up to ministry level. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Structure of china govt wang deangelis 2012.jpg | thumb | 500px | Figure 3: Political Structure of Chinese Government]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | As an inter-basin water transfer project, SNWDP involves a number of provinces and municipalities. To coordinate among different provinces, an institutional body – the South-to-North Water Diversion Project Office (SNWD Project Office) was created in 1979 to oversee the planning, design, construction and operation of the SNWDP. A committee led by the Vice Prime Minister sets the goals and policy of the Project Office. The board members of the committee include all relevant ministers, provincial governors, and municipality mayors. There are also sub-offices at the provincial and municipal levels in charge of the construction projects within their jurisdictional boundaries. In short, the central government endorses SNWD Project Office to perform a coordinative role in all issues related to the South-to-North Water Diversion Project. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Water Quality Related Regulation== | ||

| + | To assure good water quality the SNWTP Project Office created the Reservoir, the Water Pollution Control & Soil and Water Conservation Plan (hereafter referred to as “the Plan”) in 2005. According to the Plan, the water quality of the Danjiangkou Reservoir and main Han River should achieve or exceed Category II, and the tributaries flowing into Danjiangkou Reservoir should achieve or exceed Category III <ref name=" Dong & Wang 2011"> Dong, Z., & Wang, J. (2011). Quantitative standard of eco-compensation for the water source area in the middle route of the South-to-North Water Transfer Project in China. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering in China, 5(3), 459–473. doi:10.1007/s11783-010-0288-9</ref>. Eighteen control zones were created at the watershed of the reservoir. These control zones span across Shaanxi, Hubei and Henan Provinces. Three of the eighteen zones are within 5km of the Reservoir peripheral and are therefore defined as the Water Source Area Security Zone. Three zones on the far left side are the sources of Han River<ref name=" WPC 2005"> Water Pollution Control & Soil and Water Conservation Plan Drafting Committee (2005). Water Pollution Control & Soil and Water Conservation Plan of Danjiangkou Reservoir and Upstream </ref> . The soil and water conservation in these zones are essential to the water quality in the Reservoir, so together these zones are defined as the Ecological Conservation Zone. The other eleven zones in between are collectively called the Water Quality Impact Zone. The Plan computed the environmental capacity of each control zone, based on the water quality condition of the river stretch in that particular zone. By comparing the current pollution loadings with the environmental capacity of the control zones, the Plan computed the amount of loading reduction needed for each control zone <ref name=" WPC 2005"> Water Pollution Control & Soil and Water Conservation Plan Drafting Committee (2005). Water Pollution Control & Soil and Water Conservation Plan of Danjiangkou Reservoir and Upstream</ref>. | ||

| + | |Issues={{Issue | ||

| + | |Issue=Government expenditure on water quality related infrastructure projects. How will the required water quality standard be met in an equitable way? | ||

| + | |Issue Description=The cost to finance this project both in terms of short term construction and long term maintenance is very large. The economic reality for the counties in the water source country varies significantly and in some locations the tax revenue is not sufficient to cover infrastructure project costs associated with the Plan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Stakeholders | ||

| + | *SNWD Project Office (ministerial level government) | ||

| + | *Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Water Resources, Ministry of Finance | ||

| + | * Water Source Area governments and their levels | ||

| + | **Henan Province (河南省) | ||

| + | *** Nanyang City (南阳市):Xixia County (西峡县), Xichuan County (淅川县) | ||

| + | ***Luoyang City (洛阳市): Luanchuan County (栾川县), Sanmenxia City (三门峡市), Lushi County (卢氏县) | ||

| + | **Hubei Province (湖北省provincial government) | ||

| + | *** Shiyan City (十堰市): Zhangwan District Bailin Town (张湾区,柏林镇), Zhuxi County (竹溪县), Zhushan County (竹山县), Yun County (郧县), Fang County (房县), Yunxi County (郧西县) | ||

| + | ***Xiangyang City (襄阳市): Xiangzhou District Huanglong Town (襄州区,黄龙镇) | ||

| + | ***Danjiangkou City (丹江口市) | ||

| + | ** Shaanxi Province (陕西省, provincial government) | ||

| + | *** Ankang City (安康市, city government): Shiquan County (石泉县), Hanyin County (汉阴县), Ziyang County (紫阳县), Langao County (岚皋县), Xunyang County (旬阳县), Pingli County (平利县), Zhenping County (镇坪县), Baihe County (白河县), Ningxia County (宁峡县) | ||

| + | ***Shangluo City (商洛市): Shangzhou District (商周区), Zhen’an County (镇安县), Zuoshui County (柞水县), Danfeng County (丹凤县), Shangnan County (商南县), Shanyang County (山阳县) | ||

| + | ***Hanzhong City (汉中市): Hantai District (汉台区), Ningqiang County (宁强县), Lueyang County (略阳县), Mian County (勉县), Liuba County (留坝县), Nanzheng County (南郑县), Chenggu County (城固县), Yang County (洋县), Xixiang County (西乡县), Foping County (佛坪县), Zhenba County (镇巴县) | ||

| + | ***Baoji City (宝鸡市): Taibai County (太白县) | ||

| + | ** Hebei Province (河北省) | ||

| + | * Water Receiving Area | ||

| + | |NSPD=Water Quantity; Water Quality; Assets | ||

| + | |Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency | ||

| + | }}{{Issue | ||

| + | |Issue=Population affected by water quality control in the water source area | ||

| + | |Issue Description=Certain farmers will be required to cease farming their land upstream from the reservoir to preserve water quality (mitigation of runoff). A rough estimation is in the hundreds of thousands. Manufacturing plants in the area will also be displaced. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Stakeholders | ||

| + | * Yellow Ginger Industry | ||

| + | * Paper manufacturing industry | ||

| + | * Chemical production industry | ||

| + | * Metal smelting industry | ||

| + | * Ecological migration of farmers | ||

| + | * General population in water source area | ||

| + | |NSPD=Water Quantity; Water Quality; Governance; Values and Norms | ||

| + | |Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Development/humanitarian interest, Environmental interest, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens | ||

| + | }}{{Issue | ||

| + | |Issue=Costs and benefits sharing between WRA and WSA | ||

| + | |Issue Description=Due to forced ecological migration of farmers and the shut-down of factories in the Water Source Area, the WSA will be bearing the greatest social and economic burden of the Plan. The Water Receiving Area will enjoy the benefit of water delivery, without the burdens borne by the WSA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Stakeholders | ||

| + | *Water Receiving Area (WRA) | ||

| + | *Water Source Area (WSA) | ||

| + | *SNWD Project Office | ||

| + | |NSPD=Governance; Assets; Values and Norms | ||

| + | |Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens | ||

| + | }}{{Issue | ||

| + | |Issue=Involving stakeholders in decision making process | ||

| + | |Issue Description=The Chinese governance structure is hierarchical; and most of the policy design and implementation process is top-down. If a long-term mechanism were to be proposed and implemented, how can we involve the stakeholders (county governments, farmers, unemployed workers) in the design and implementation of the mechanism? | ||

| + | |NSPD=Water Quality; Assets; Values and Norms | ||

| + | |Stakeholder Type=Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Sovereign state/national/federal government, Community or organized citizens | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |Key Questions={{Key Question | ||

| + | |Subject=Urban Water Systems and Water Treatment | ||

| + | |Key Question - Dams= | ||

| + | |Key Question - Urban=How can costs for water quality projects be distributed between polluters and beneficiaries? | ||

| + | |Key Question - Transboundary= | ||

| + | |Key Question - Desalination= | ||

| + | |Key Question - Influence= | ||

| + | |Key Question - Industries= | ||

| + | |Key Question Description=A Payment for Water Quality Services (PWQS) scheme could provide a method for investigating ways that the Water Source Area and Water Receiving Area might share the costs associated with the project. | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |Summary=This case study addresses the issues of cost-benefit sharing between Water Source Area (WSA) and Water Receiving Area (WRA) in a large-scale water transfer project in China. The proposed water quality control projects in the WSA of China’s South-to-North Water Transfer Project (SNWTP) Middle Route Project (MRP) affect industrial and agricultural sectors in the WSA. The water quality control projects primarily benefit communities in the WRA through improved water quality and decreased treatment costs, although the WSA also receives some benefits including water quality and ecosystem improvements. The water quality control projects have both direct and indirect costs which are primarily borne by the WSA communities. The WRA is more economically developed and have a higher per capita GDP than the WSA and watershed protection requirements will restrict development options in the WSA which adds to concerns of equity in the division of project costs and benefits. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) has been proposed as a compensation mechanism to redistribute the expenses of water quality services among the stakeholders in an equitable and effective manner. The Chinese Ministry of Finance has authorized transfer payments to the source area for ecosystem services. While PES has been used previously in China, criteria for quantifying compensation is poorly defined and some argue that authorized payments are insufficient. This case focuses on PES as a compensation mechanism and explores methods to quantify fair compensation. | ||

| + | ==Questions and Wisdom== | ||

| + | Central to this case are questions of water quality and equity: 1) how can stakeholders place economic value on efforts to enhance water quality and, most importantly, 2) how can stakeholders distribute the costs of water quality projects amongst polluters and beneficiaries? Here we find that hierarchical structures and limited stakeholder involvement in water projects can lead to unbalanced distribution of costs and benefits. The issues in the SNWD MRP demonstrate the need for cost-sharing mechanisms as part of an institutional governance structure in water quality projects. When stakeholders have disproportionate costs and benefits associated with enhancing water quality, a financing instrument can help to place economic value on environmental and social factors. | ||

| + | |External Links= | ||

| + | |Case Review={{Case Review Boxes | ||

| + | |Empty Section=Yes | ||

| + | |Clean Up Required=Yes | ||

| + | |Expand Section=Yes | ||

| + | |Add References=No | ||

| + | |Wikify=No | ||

| + | |connect to www=No | ||

| + | |Out of Date=No | ||

| + | |Disputed=No | ||

| + | |MPOV=No | ||

| + | |Mpov=No | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |ASI={{ASI | ||

| + | |Contributor=Kelly DeAngelis (Boston University), Rose Wang (Tufts University) | ||

| + | |ASI=====Problem Definition==== | ||

| + | The SNWDP presents the challenge of ensuring water quality in a long-range inter-basin water transfer. In order to enhance the quality of water in the Water Receiving Area (WRA), there must be improvements in the Water Source Area (WSA). The thousands of proposed pollution control projects require billions of dollars in the short and long term. Having the relatively poorer Water Source Area contribute water and pay for the water quality control projects is unjustifiable. Therefore, in this case study, we analyzed the affected stakeholders and proposed a mechanism to share benefits and costs between WRA and WSA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Issue Analysis==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The major issue in this case study is how to achieve the water quality standard required by the Plan in an equitable way. In this section, we analyze some sub-issues, relevant stakeholders of the sub-issues, and the variables linked to the sub-issues and stakeholders. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Issue 1: Government expenditure on water quality related infrastructure projects==== | ||

| + | As mentioned in the Background section, the costs of the short-term and long-term projects are huge. Among the 43 counties in the water source area, 26 are National Impoverished Counties and 8 are Provincial Impoverished Counties. The tax revenues of those counties are obviously insufficient to pay for the expensive infrastructure projects required by the Plan. Although the Ministry of Finance (representing the central government) has provided some funding assistance since 2008, the assistance was via a general purpose fiscal transfer instead of a special purpose transfer (for water quality control). The details of the assistance and how the funding was used are unclear. In this sub-issue, the stakeholders are mostly government bodies and the variables are Governance, Assets and Water Quality. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Issue 2: Population affected by water quality control in the water source area==== | ||

| + | Hundreds of thousands of people in the water source area will, directly or indirectly, positively or negatively, be affected by the water quality control projects. The first category is farmers who will be affected by “ecological migration” and industrial point-source removal. Ecological migration is an emerging concept in China. Unlike traditional migration, the population forced to leave is not located at the reservoir inundation, area such as it was in Three Gorges Dam project. Though the farmers in the WSA live upstream of the Reservoir, their agricultural practices or living activities will affect the water quality in the reservoir, and therefore they must leave the area. Those who will be considered for migration include: 1) farmers who live in mountainous areas without access to grid who deforest trees for fuel; 2) farmers who cultivate on steep slopes (steeper than 25 degree, for example) not suitable for agriculture and contribute to landslides and water and soil loss, 3) farmers whose agricultural practices and daily life cause non-point source pollution to the rivers and reservoirs. There is no published data on the total number of people who will be migrated. The rough estimation is of the order of hundreds of thousands. For example, Yun County (郧县) of Shiyan City (十堰市) in Hubei Province alone has 28817 people (7229 family) to be migrated into 79 settlement locations. These settlement locations are usually within or near the same town they used to live in (内安政策) but usually have better access to roads, centralized waste disposal infrastructure or electricity grid. The photos below show two of the settlements in Yun County. In addition to ecological migration, farmers will also be affected by industrial point source removal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yellow ginger (turmeric) industry is one of the biggest industries in the water source area. Yellow ginger contains saponin, a valuable element for heart disease medicine. China supplies approximately 90% of the Saponin in the world, and about 40% of Chinese manufactured saponin was from the Middle Route Water Source Area. Because of its rarity, locals call yellow ginger “soft gold.” More than one million people in the water source area were relying on the chain of yellow ginger cultivation, saponin manufacturing and sales. However, the traditional manufacturing process of saponin is very energy intensive and pollutive (Figure 2). To produce 1t of saponin, it takes 180t yellow ginger, 20t hydrogen chloride, 6t gasoline, 50t coal, and 500t water. Most of water used in the process is turned into acidic wastewater containing high concentration of COD (12 times more than paper manufacturing industry). To achieve the loading reduction required by the Plan, hundreds of saponin manufacturing plants were closed down and some are suspended until they can reach the emission standard. Workers lost their jobs. Additionally, because of factories closures, the yellow ginger cultivation area reduced from 330,000 hectares to 60,000 hectares. Farmers lost an important stream of income and large amount of workers were unemployed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another big industry affected by the water quality control plan is the paper manufacturing industry. Tailong Paper Manufacturing Company (泰龙造纸厂), for example, which used to produce 1/3 of GDP of Xichuan County, contribute 20 million CNY annually to its tax revenue, and employ 1700 workers was closed down in 2004 for environmental compliance. Four thousand other paper mills were shut down in the water source area. Other affected industries include mining, metal smelting, chemical production industry, and more. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Issue 3: Costs and benefits sharing between WRA and WSA==== | ||

| + | Even though the shut-down of pollutive factories has important benefits to both the ecosystem health of the Water Source Area and water quality for Water Receiving Area, the social and economic burden is borne only by the Water Source Area. It is unjustifiable for the impoverished water source area to not only contribute its water, but also bear the social and economic cost of water quality control projects. Although, one-time fiscal funding contributions from the central government can temporarily solve some emergent shortage, a long-term mechanism needs to be in place to make sure the costs and benefits are shared fairly between the water receiving area and the water source area. In the synthesis part of this section, we propose a mechanism called “Payment for Water Quality Services (PWQS)” to realize this equity goal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Issue 4: involving stakeholders in decision making process==== | ||

| + | The Chinese governance structure is hierarchical; and most of the policy design and implementation process is top-down. However, the term “public participation” has appeared more often in recent literatures of social science and environmental management | ||

| + | <ref name="Zhong et al 2008"> Zhong, L.-J. & Mol, A.P.J. Participatory environmental governance in China: public hearings on urban water tariff setting. Journal of environmental management 88, 899-913 (2008). </ref> | ||

| + | <ref name=" Li et al 2012"> Li, W., Liu, J. & Li, D. Getting their voices heard: three cases of public participation in environmental protection in China. Journal of environmental management 98, 65-72 (2012). </ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Zhao et al 2010 "> Zhao, Y. Public Participation in China’s EIA Regime: Rhetoric or Reality? Journal of Environmental Law 22, 89-123 (2010). </ref>.If a long-term mechanism were to be proposed and implemented, how can we involve the stakeholders (county governments, farmers, unemployed workers) in the design and implementation of the mechanism? This is another issue of interest in this case. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Synthesis=== | ||

| + | ===Payment for Water Quality Services (PWQS)=== | ||

| + | After analyzing the issues and the affected stakeholders, we propose implementing a scheme of Payment for Water Quality Services (PWQS). Water Quality Services are any measures taken to enhance water quality, including pollution control, land-use changes, technical investments, etc <ref name ="Kemekes et al 2010"> Kemkes, R.J., Farley, J. & Koliba, C.J. Determining when payments are an effective policy approach to ecosystem service provision. Ecological Economics 69, 2069-2074 (2010).</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | PWQS is based on the concept of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES)<Ref name="Forest Trends et al 2008"> Forest Trends, The Katoomba Group, and UNEP. Payments for Ecosystem Services : Getting Started Payments for Ecosystem Services Getting Started : A Primer. Prospects (Nairobi, 2008). </ref>. . Some common practices of PES include emissions cap-and-trade systems to limit total pollution and allow the market mechanism to regulate polluting sources. Emissions trading systems have been used for nutrient pollution in water sources, and carbon in the EU. Reforestation is another form of PES, in which landowners are compensated for the planting costs or opportunity cost of planting trees instead of using land for alternate, often polluting, uses. Another form of PES is incentivizing farmers to convert to more sustainable methods of agriculture. Public or private actors on individual or collective scales may choose to implement these types of PES structures in order to reap environmental benefits such as water or air quality, soil conservation, or habitat restoration<ref name="Forest Trends 2008" />. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Payments for Watershed Services (PWS)<ref name="Forest Trends 2008"> Forest Trends and the Ecosystem Marketplace Payments for Ecosystem Services: Market Profiles. (2008). </ref> is another scheme on which PWQS is based. PWS involves reducing poverty by using payment systems to maximize watershed services. Because of the ability of PWS to address poverty reduction in addition to environmental concerns, these schemes have been designated “pro-poor.”<ref name="Pagiola 2007"> Pagiola, S. Guidelines for “Pro-Poor” Payments for Enviornmental Services. (2007).</ref> The PWQS scheme we proposed is specialized to combine environmental, economic, and social benefits by incentivizing PES measures to enhance water quality and PWS methods to provide other societal benefits to a disadvantaged and affected population. Pro-poor benefits are integral to the societal aspect of PWQS. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Evaluation, Collection and Distribution of PWQS=== | ||

| + | In order to ensure the success of a PWQS scheme, the payments must be valued correctly<ref name="Farley et al 2010"> Farley, J. & Costanza, R. Payments for ecosystem services: From local to global. Ecological Economics 69, 2060-2068 (2010). </ref>, and the collection and distribution must be transparent and equitable so that they are acceptable to both buyers and sellers of water quality services. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sufficient valuation begins with the water quality standards. When regulators raise standards, the Water Source Area must take measures to ensure that the water will meet the new requirements, such as removing industrial point source pollution, installing wastewater treatment plants, implementing landfill projects, or employing soil and water conservation projects. In this case, Beijing requires that the water quality at Danjiangkou Reservoir must reach Grade II and its inflow tributaries must reach Grade III. Based on the requirement, the stakeholders should evaluate the costs of the necessary changes depending on what action they choose to take. Costs can be economic, financial, and social. For example, if a heavily polluting industrial factory must be shut down, the cost of the water quality service is the lost economic value of the factory to the community and the resulting unemployment. The value of enhanced water treatment is equivalent to the construction costs of new infrastructure projects that will raise water quality. Development opportunity costs are also part of the value of water quality services, including the financial loss of companies that will not operate in the water source area because of the stringent water requirements. The lost jobs and necessity of ecological migration are some social costs that changes in water quality may bring. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once the relevant stakeholders evaluate the costs, there are different methods of collection to capture the payments for water quality services. One method is to adjust water-pricing mechanisms, therefore generating revenue by charging recipients per unit volume of clean water resulting from water quality services. Direct payment is another collection method, in which recipients contribute financial resources from an existing tax revenue base. There is always an option to create a new collection fund for PWQS, which would benefit from multiple sources. Central government finances could contribute national tax revenue to large projects as part of a top-down structure. Lateral contributions from WRA to WSA governments at the same level, such as provincial-to-provincial, would also be effective and directly relevant to the water quality issue. Smaller partnerships between WSA county level governments and WRA county level governments are also possible options. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once stakeholders establish mechanisms for collection of PWQS, they must create systems for the equitable distribution of payments to the providers of water quality services. The first priority of PWQS is to generate multiple benefits from limited funds. Payments made for enhancing water quality should also benefit the disadvantaged population, which is what we proposed as “pro-poor strategies”. Pro-poor strategies involve reimbursing the sacrifices of the people in the Water Source Area. This includes compensation for unemployment and resettlement costs resulting from factory shutdowns. When payments are distributed to those who were forced to relocate, payments should increase living standards of the formerly disadvantaged population. Water Source Areas in need of social services such as schools, medical clinics, etc. should be able to use finances from PWQS to assist the community. These methods are examples of pro-poor distribution possibilities benefit individuals. In addition, payments should also account for the costs of training and technical support necessary to account for sustainable practices or land-use changes necessary to increase water quality. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Payments for Water Quality Services are necessary to rebalance the burden and the benefits of providing clean water, so whatever institutions are created to monitor the collection and distribution of payments should also recognize the rights of the participants. When PWQS schemes are initiated, the institutions should allow for individuals and communities to be more involved in the decision-making process to make sure that payments are being used effectively. Instruments to ensure the effectiveness of PWQS could include incremental reports, a formal process for appeals, or comment periods to evaluate the validity of complaints or suggestions. Payments should also be used as financial support for significant community goals, when appropriate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are also possibilities for more general payments to be used on the collective or individual basis. Direct payments can be used to finance the general transition from polluting to sustainable industries. The opportunity cost of losing industrial business, or the cost of converting one industry to another could be accounted for with direct payments. PQWS also includes the possibility of per-project payments, in which beneficiaries contribute resources to specific water quality enhancement ventures. In the case of constructing a waste treatment facility, for example, funds could supply money for construction of the facility in the water source area, or external sources could take the responsibility of building the facility to ensure their own water quality. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Indirect payments are other options for compensating water quality services. These are to cover costs associated with reforming local industrial and agricultural sectors to conform to more sustainable practices. The first obstacle is integrating sustainable development into existing infrastructure. Locals can generate income and stimulate the economy from alternative land-uses that increase water quality and benefit the environment. An opportunity for local farmers is transforming environmentally harmful practices into eco-agriculture. Restoring, preserving, and maintaining local environmental attractions can lead to the development of an eco-tourism industry. In-kind payments, such as products or training necessary for shifting to alternate lifestyles or land-uses are also forms of indirect payments for using sustainable practices. Introducing sustainable development requires a strong partnership between the buyers and sellers of WQS, which will only come when both sides can recognize the mutual benefits of working together. Recipients will be willing to pay for better water quality, and donors will continue water quality services if they feel that that compensation is adequate. When benefits equal or outweigh costs, commitments on both sides will be reinforced. Close linkages between the water source and water receiving areas will also ensure that recipients will use PWQS as intended. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another important use of PWQS is educational campaigns to promote awareness of water quality issues and community involvement. A collective local understanding of the PWQS allows for greater distribution of services and payments, and gives the community a stronger voice in the decision-making process. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In order to distribute costs equitably, stakeholders should create cost-sharing mechanisms to lessen the burden of creating water quality services. Public funding is likely to be a major source of resources for PWQS. Financing can come from the central, provincial, county, or local level. Capital can flow through top-down transfers between government levels, or horizontal transfers along the same government levels. However, initial costs are often high, and public funding is often limited. Therefore, there are great opportunities for mutual investment of public and private funding. Companies that can maintain water quality standards may have interest in bidding for the privilege to operate in the water source areas. This will lessen the burden to the public sector and encourage investment and clean development. All water quality schemes should consider raising support and funding from outside investors, such as NGOs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Implementing PWQS – the Intervention Point=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The above proposed PWQS is, by any means, a negotiation process. The implementation of the scheme requires a neutral organization to facilitate and mediate between WSA and WRA. In other words, there must be an intervention point in the existing governance structure. We propose creating a sub-committee under the SNWD Project Office to coordinate the negotiation processes between the water source and receiving areas. This sub-committee will facilitate the joint fact finding process to evaluate the costs of water quality enhancement. It can work with both regions to develop a detailed plan for the collection and distribution of payments for water quality services. Additionally, the sub-committee would design a conflict resolution mechanism to deal with problems as they arise and allow for flexibility within the new PWQS system. | ||

| + | |ASISummary=Here, we provide analysis of benefits in the water receiving area (WRA) and costs to the water source area (WSA). We propose a system for "Payments for Water Quality Services" as a solution to the issue of rebalancing the burden and the benefits of providing clean water. | ||

| + | |User=Kelly DeAngelis | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |Figure 6: Water Source and Receiving Area of MRP_ See image for base map source info | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The Water Source Area (WSA) of the Middle Route spans across Hubei, Shaanxi and Henan province_ The Water Receiving Area (WRA) includes Beijing, Tianjin, Henan and Hebei provinces (Figure 2)_ Henan province is both WSA and WRA_ | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 1 summarizes the economic indicators for the provinces and municipalities of the water source area and water receiving area_ As the table shows, the GDP per person of Beijing and Tianjin are about three times of the other provinces_ It is obvious from the figure that water source area is generally much poorer than the water receiving area_ | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Tables 1a and 1b: Economic facts of the Water Source Area (WSA) and Water Receiving Area (WRA) provinces/municipalities source <ref name="Economist China"> The Economist. "Comparing Chinese provinces with countries: All the parities in China". (201AD).at [http://www.economist.com/content/all_parities_china]. retrieved May 2012. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 1a WRA | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| | ||

| + | | A || B | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | C || D | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | As mentioned previously, the Plan guides much of the water quality control efforts for the Danjiangkou Reservoir. Based on loading reduction targets for each control zone, the Plan includes several lists of projects to invest in, which include wastewater treatment plants, landfills, eco-agriculture, soil and water conservation, wetland protection, etc. Eight-hundred and seventy-eight projects were proposed to be carried out in the short term, which will cost 6.989 billion CNY (Chinese Yuan). Another 1,234 projects were planned for the long term, which would cost 12.444 billion CNY. The breakdown of the costs of the projects is shown in Table 2. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The amount of work needed to be done is enormous, but it is not clear in the Plan who will bear the cost of these projects. Up to now, there is no clear-cut long term mechanism in place to finance those projects. If there financing instrument for the planned water quality control projects, the burden on local economy and local people will be unbearable. For example, according to Dong et al.<ref name="Dong et al 2006"> Dong, Z. et al. Computing payment for ecosystem services in watersheds: An analysis of the Middle Route Project of South-to-North Water Diversion in China. ''Journal of Environmental Sciences'' 23, 2005-2012 (2011).</ref>, Shiyan City, one of the cities in the Water Source Area Security Zone in Hubei Province, has shut down a large number of polluting enterprises, including 3,622 paper mills. It has spent 5.34 billion CNY on water quality control projects, and its financial revenue has reduced by 0.65 billion CNY due to the closure of the pollution-cause enterprises. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 2 Breakdown of water quality control projects and their costs <ref name="Water Pollution 2005"/> | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 09:47, 13 March 2013

| Geolocation: | 32° 36' 0", 111° 35' 60" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 11.9811,980,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 9500095,000 km² 36,679.5 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | temperate |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, industrial use, urban |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Industry - consumptive use, Industry - non-consumptive use |

| Water Features: | Han River (Yangtze River), Danjiangkou Reservoir |

| Riparians: | China |

| Water Projects: | South-North Water Transfer Project |

Contents

Summary

This case study addresses the issues of cost-benefit sharing between Water Source Area (WSA) and Water Receiving Area (WRA) in a large-scale water transfer project in China. The proposed water quality control projects in the WSA of China’s South-to-North Water Transfer Project (SNWTP) Middle Route Project (MRP) affect industrial and agricultural sectors in the WSA. The water quality control projects primarily benefit communities in the WRA through improved water quality and decreased treatment costs, although the WSA also receives some benefits including water quality and ecosystem improvements. The water quality control projects have both direct and indirect costs which are primarily borne by the WSA communities. The WRA is more economically developed and have a higher per capita GDP than the WSA and watershed protection requirements will restrict development options in the WSA which adds to concerns of equity in the division of project costs and benefits. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) has been proposed as a compensation mechanism to redistribute the expenses of water quality services among the stakeholders in an equitable and effective manner. The Chinese Ministry of Finance has authorized transfer payments to the source area for ecosystem services. While PES has been used previously in China, criteria for quantifying compensation is poorly defined and some argue that authorized payments are insufficient. This case focuses on PES as a compensation mechanism and explores methods to quantify fair compensation.

Questions and Wisdom

Central to this case are questions of water quality and equity: 1) how can stakeholders place economic value on efforts to enhance water quality and, most importantly, 2) how can stakeholders distribute the costs of water quality projects amongst polluters and beneficiaries? Here we find that hierarchical structures and limited stakeholder involvement in water projects can lead to unbalanced distribution of costs and benefits. The issues in the SNWD MRP demonstrate the need for cost-sharing mechanisms as part of an institutional governance structure in water quality projects. When stakeholders have disproportionate costs and benefits associated with enhancing water quality, a financing instrument can help to place economic value on environmental and social factors.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

Introduction

China has low water availability, with per capita annually renewable water resources of about one quarter of the global average [1]. The problem of low per capita water availability is exacerbated by the fact that the spatial distribution of water resources does not match the distribution of population and industry [2]. The majority of precipitation and surface water is located in the South, while water demands are much higher in the North due to the greater agricultural production and as well as the populous, industrialized cities [2]. In the North (the Hai, Huai, and Huang (Yellow River) watersheds) per capita annual water resources are just ranges from 225 to 656 m3 across the watersheds while in the South, in the Yangtze River watershed, per capita water availability is 2,100 m3 [3] [4]. Water availability across the Northern region, is below the United Nations threshold for water scarcity of 1,000 m3 per capita [5].

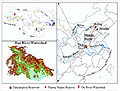

The idea of transferring water from the South the North first arose in the early 1950’s. The late Chairman Mao suggested “borrowing” water from the South to meet the demands of the North [6]. The concept was ambitious. The scheme involved transferring water over 1,000 km which would require a huge investment in capital and require overcoming significant engineering challenges [6]. Over the next several decades, scientists and engineers debated the technical and economic feasibility of Mao’s vision. Engineering studies of the proposed transfer began in the 1950’s at which time three alignments were described: the Eastern Route, the Middle Route, and the Western Route (Figure 1)[7]. The Eastern Route diverts water from the Yangtze approximately 100 km below Nanjing and transfers it North to Tianjin; the Middle Route extracts water from the Danjiangkou Reservoir (Figure 2) on the Han River, a tributary to the Yangtze and diverts it to Beijing; the Western Route diverts water from the upper Yangtze tributaries to the arid Northwestern region [7].

In 2002, the South-to-North Water Division Project (SNWDP) was approved and construction began on the Eastern Route [8]. Construction has since begun on the Middle Route but has not yet begun on the Western Route. The government plans to complete construction of the Eastern and Middle Routes by 2013 and 2014 respectively [9]. As the construction of the projects proceeds, one question arises: what will the water quality of water delivered to the north be? According to the plans, water in the Danjiangkou Reservoir, the water source for the Middle Route, should exceed the Chinese Surface Water Standard for class II water [10]. Poor water quality would increase treatment cost. Water quality can be improved and controlled through watershed protection measures in the South; however, this has both direct and indirect costs for communities in the South [10]. The majority of the focus on water quality has been on the Middle Route which when complete will be the largest water transfer in the world; within the Middle Route watershed, Shiyan City has been the focus of watershed protection schemes because it is the largest city located in the Danjiangkou Reservoir source protection area and has the longest reservoir shoreline [11]. Planned watershed protection actions require capital investments and restrict development options for Shiyan City and the surrounding area. For this reason, the receiving area, the North, is expected to compensate the source area for their conservation efforts. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) has been implemented in China before but criteria for fair compensation is not clear [11]. This case study will focus on the water quality control in Middle Route source area and the use of PES to compensate the source area residents for their direct and indirect costs.

Governance Framework

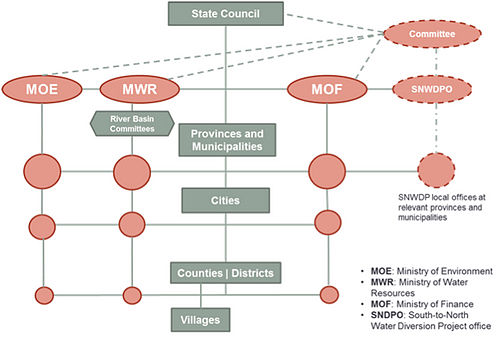

To understand the political framework of the topic of interest, we need to first take a look at the political framework of Chinese government system, as shown in Figure 3. The top administrative organization is called the State Council, followed hierarchically by provinces and Municipalities, cities, counties or districts, and villages. There are also Autonomous Regions (e.g. Xinjiang and Tibet), as well as Special Administrative Regions (e.g. Hongkong and Macau), which are at the same level as provinces. Ministries, such as Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Water Resources, etc., are executive bodies under the direct lead of the State Council. Departments of similar functions (environmental protection, water resources, etc.) take responsibility at the provincial, city, and even district level; they report to their superior organizations up to ministry level.

As an inter-basin water transfer project, SNWDP involves a number of provinces and municipalities. To coordinate among different provinces, an institutional body – the South-to-North Water Diversion Project Office (SNWD Project Office) was created in 1979 to oversee the planning, design, construction and operation of the SNWDP. A committee led by the Vice Prime Minister sets the goals and policy of the Project Office. The board members of the committee include all relevant ministers, provincial governors, and municipality mayors. There are also sub-offices at the provincial and municipal levels in charge of the construction projects within their jurisdictional boundaries. In short, the central government endorses SNWD Project Office to perform a coordinative role in all issues related to the South-to-North Water Diversion Project.

Water Quality Related Regulation

To assure good water quality the SNWTP Project Office created the Reservoir, the Water Pollution Control & Soil and Water Conservation Plan (hereafter referred to as “the Plan”) in 2005. According to the Plan, the water quality of the Danjiangkou Reservoir and main Han River should achieve or exceed Category II, and the tributaries flowing into Danjiangkou Reservoir should achieve or exceed Category III [10]. Eighteen control zones were created at the watershed of the reservoir. These control zones span across Shaanxi, Hubei and Henan Provinces. Three of the eighteen zones are within 5km of the Reservoir peripheral and are therefore defined as the Water Source Area Security Zone. Three zones on the far left side are the sources of Han River[12] . The soil and water conservation in these zones are essential to the water quality in the Reservoir, so together these zones are defined as the Ecological Conservation Zone. The other eleven zones in between are collectively called the Water Quality Impact Zone. The Plan computed the environmental capacity of each control zone, based on the water quality condition of the river stretch in that particular zone. By comparing the current pollution loadings with the environmental capacity of the control zones, the Plan computed the amount of loading reduction needed for each control zone [12].

Issues and Stakeholders

Government expenditure on water quality related infrastructure projects. How will the required water quality standard be met in an equitable way?

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency

The cost to finance this project both in terms of short term construction and long term maintenance is very large. The economic reality for the counties in the water source country varies significantly and in some locations the tax revenue is not sufficient to cover infrastructure project costs associated with the Plan.

Stakeholders

- SNWD Project Office (ministerial level government)

- Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Water Resources, Ministry of Finance

- Water Source Area governments and their levels

- Henan Province (河南省)

- Nanyang City (南阳市):Xixia County (西峡县), Xichuan County (淅川县)

- Luoyang City (洛阳市): Luanchuan County (栾川县), Sanmenxia City (三门峡市), Lushi County (卢氏县)

- Hubei Province (湖北省provincial government)

- Shiyan City (十堰市): Zhangwan District Bailin Town (张湾区,柏林镇), Zhuxi County (竹溪县), Zhushan County (竹山县), Yun County (郧县), Fang County (房县), Yunxi County (郧西县)

- Xiangyang City (襄阳市): Xiangzhou District Huanglong Town (襄州区,黄龙镇)

- Danjiangkou City (丹江口市)

- Shaanxi Province (陕西省, provincial government)

- Ankang City (安康市, city government): Shiquan County (石泉县), Hanyin County (汉阴县), Ziyang County (紫阳县), Langao County (岚皋县), Xunyang County (旬阳县), Pingli County (平利县), Zhenping County (镇坪县), Baihe County (白河县), Ningxia County (宁峡县)

- Shangluo City (商洛市): Shangzhou District (商周区), Zhen’an County (镇安县), Zuoshui County (柞水县), Danfeng County (丹凤县), Shangnan County (商南县), Shanyang County (山阳县)

- Hanzhong City (汉中市): Hantai District (汉台区), Ningqiang County (宁强县), Lueyang County (略阳县), Mian County (勉县), Liuba County (留坝县), Nanzheng County (南郑县), Chenggu County (城固县), Yang County (洋县), Xixiang County (西乡县), Foping County (佛坪县), Zhenba County (镇巴县)

- Baoji City (宝鸡市): Taibai County (太白县)

- Hebei Province (河北省)

- Henan Province (河南省)

- Water Receiving Area

Population affected by water quality control in the water source area

NSPD: Water Quantity, Water Quality, Governance, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Development/humanitarian interest, Environmental interest, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens

Certain farmers will be required to cease farming their land upstream from the reservoir to preserve water quality (mitigation of runoff). A rough estimation is in the hundreds of thousands. Manufacturing plants in the area will also be displaced.

Stakeholders

- Yellow Ginger Industry

- Paper manufacturing industry

- Chemical production industry

- Metal smelting industry

- Ecological migration of farmers

- General population in water source area

Costs and benefits sharing between WRA and WSA

NSPD: Governance, Assets, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Industry/Corporate Interest, Community or organized citizens

Due to forced ecological migration of farmers and the shut-down of factories in the Water Source Area, the WSA will be bearing the greatest social and economic burden of the Plan. The Water Receiving Area will enjoy the benefit of water delivery, without the burdens borne by the WSA.

Stakeholders

- Water Receiving Area (WRA)

- Water Source Area (WSA)

- SNWD Project Office

Involving stakeholders in decision making process

NSPD: Water Quality, Assets, Values and Norms

Stakeholder Types: Federated state/territorial/provincial government, Sovereign state/national/federal government, Community or organized citizens

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:Alternative Solutions to the Water Demand of Northern China

Concerning the ultimate problem of imbalance water demand distribution in the Northern and Southern China, scholars suggest implementations that will further consider China's water sustainability other than water diversion.(read the full article... )

Contributed by: Samuel Hsiao (last edit: 1 August 2013)

ASI:Determining Fair Payment for Ecosystem Services

Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES), a voluntary exchange of a defined environmental service for a fee, has been previously implemented in China there is no consensus on criteria for fair compensation. Planned water quality control actions require capital investments and restrict development options for the water source area. For this reason, the receiving area is expected to compensate the source area for their conservation efforts. How should PES payments be determined?(read the full article... )

Contributed by: Margaret Garcia (last edit: 19 March 2013)

Key Questions

Urban Water Systems and Water Treatment: How can costs for water quality projects be distributed between polluters and beneficiaries?

A Payment for Water Quality Services (PWQS) scheme could provide a method for investigating ways that the Water Source Area and Water Receiving Area might share the costs associated with the project.

- ^ World Bank. (2002).World Development Indicators 2002. Retrieved from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2002/10/12/000094946_0210120412542/Rendered/PDF/multi0page.pdf

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Zhang, Q. (2009). The South-to-North Water Transfer Project of China: Environmental Implications and Monitoring Strategy. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 45(5), 1238–1247. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2009.00357.x

- ^ Varis, O., & Vakkilainen, P. (2001). China’s 8 challenges to water resources management in the first quarter of the 21st Century. Geomorphology, 41(2-3), 93–104. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(01)00107-6

- ^ Shao, X., Wang, H., & Wang, Z. (2003). International Journal of River Basin Management Interbasin transfer projects and their implications : A China case study. International Journal of River Basin Management, 1(1), 37–41.

- ^ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2013). International Decade for Action ‘Water for Life’ 2005-2015: Water Scarcity. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Yang, H., & Zehnder, A. J. B. (2005). The South-North Water Transfer Project in China The South-North Water Transfer Project in China An Analysis of Water Demand Uncertainty and Environmental, (February 2013), 37–41.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Berkoff, J. (2003). China : The South – North Water Transfer Project — is it justified ? Water Policy, 5, 1–28.

- ^ Zhang, Q., Xu, Z., Shen, Z., Li, S., & Wang, S. (2009). The Han River watershed management initiative for the South-to-North Water Transfer project (Middle Route) of China. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 148(1-4), 369–77. doi:10.1007/s10661-008-0167-z.

- ^ Wong, E. (2011, June 1). Plan for China’s Water Crisis Spurs Concern. The New York Times. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/02/world/asia/02water.html?pagewanted=all.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Dong, Z., & Wang, J. (2011). Quantitative standard of eco-compensation for the water source area in the middle route of the South-to-North Water Transfer Project in China. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering in China, 5(3), 459–473. doi:10.1007/s11783-010-0288-9

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Dong, Z., Yan, Y., Duan, J., Fu, X., Zhou, Q., Huang, X., Zhu, X., et al. (2011). Computing payment for ecosystem services in watersheds: An analysis of the Middle Route Project of South-to-North Water Diversion in China. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 23(12), 2005–2012. doi:10.1016/S1001-0742(10)60663-8

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Water Pollution Control & Soil and Water Conservation Plan Drafting Committee (2005). Water Pollution Control & Soil and Water Conservation Plan of Danjiangkou Reservoir and Upstream