Difference between revisions of "The Lesotho Highlands Water Project"

Templates/files updated (unreviewed pages in bold): Template:ASI Summary, Template:Case Description, Template:Case Study, Template:Key Question

| [checked revision] | [checked revision] |

Mpritchard (Talk | contribs) |

Mpritchard (Talk | contribs) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 13:46, 29 August 2012

| Geolocation: | -29° 30' 53.2238", 28° 34' 47.2732" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 13,002,50013,002,500,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 944,051944,051 km² 364,498.091 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Dry-summer, temperate |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | rangeland, urban |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply, Hydropower Generation |

| Agreements: | Treaty on the Lesotho Highlands Water Project between the government of the Republic of South Africa and the government of the Kingdom of Lesotho |

Contents

Summary

Development in Lesotho has been limited by its lack of natural resources and investment capital. Water is its only abundant resource, which is precisely what regions of neighboring South Africa have been lacking. A project to transfer water from the Senqu River to South Africa had been investigated in the 1950s, and again in the 1960s. The project was never implemented due to disagreement over appropriate payment for the water. In 1978, the governments of Lesotho and South Africa appointed a joint technical team to investigate the possibility of a water transfer project. A treaty between the two states was necessary to negotiate for this international project. Negotiations proceeded through 1986 and the "Treaty on the Lesotho Highlands Water Project between the Government of the Kingdom of Lesotho and the Government of the Republic of South Africa " was signed into law on October 24, 1986. The Treaty spells out an elaborate arrangement of technical, economic, and political intricacy. The water transfer component was entirely financed by South Africa, which would also make payments for the water that would be delivered. The hydropower and development components were undertaken by Lesotho, which received international aid from a variety of donor agencies, particularly the World Bank. Phase IA of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project was completed in 1998, at a cost of $2.4 billion. Phase IB of the project was completed in early 2004, as a cost of approximately $1.5 billion. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project provides lessons in the importance of an integrated approach to negotiating the allocation of a "basket" of resources. South Africa receives cost-effective water for its continued growth, while Lesotho receives revenue and hydropower for its own development.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

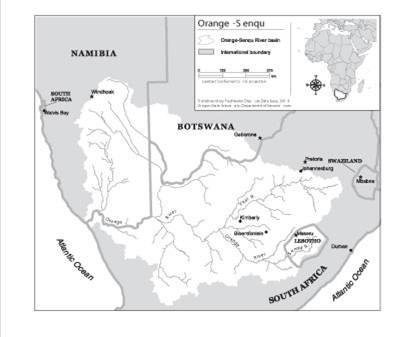

Image 1. Map of the Senqu River (Lesotho Highlands Project)[1]

Image 1. Map of the Senqu River (Lesotho Highlands Project)[1]

Background

Development in Lesotho has been limited by its lack of natural resources and investment capital. Water is its only abundant resource, which is precisely what regions of neighboring South Africa have been lacking. A project to transfer water from the Senqu River to South Africa had been investigated in the 1950s, and again in the 1960s. The project was never implemented due to disagreement over appropriate payment for the water.

The Problem

Lesotho, completely surrounded by South Africa, is a state poor in most natural resources, water being the exception. The industrial hub of South Africa, from Pretoria to Witwatersrand, has been exploiting most of the local water resources for years and the South African government has been in search of alternate sources. The elaborate technical and financial arrangements that led to construction of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) provide a good example of the possible gains of an integrative arrangement including a diverse "basket" of benefits.

Attempts at Conflict Management

In 1978, the governments of Lesotho and South Africa appointed a joint technical team to investigate the possibility of a water transfer project. The first feasibility study suggested a project to transfer 35 m3/sec, four dams, 100 km of transfer tunnel, and a hydropower component. Agreement was reached to study the project in more detail, the cost of the study to be borne by both governments.

The second feasibility study, completed in 1986, concluded that the project was feasible, and recommended that the amount of water to be transferred be doubled to 70 m3/sec. A treaty between the two states was necessary to negotiate for this international project. Negotiations proceeded through 1986 and the "Treaty on the Lesotho Highlands Water Project between the Government of the Kingdom of Lesotho and the Government of the Republic of South Africa " was signed into law on October 24, 1986.

It is testimony to the resilience of these arrangements that no significant changes were made despite the dramatic political shifts in South Africa at the end of the 1980s until 1990.

Outcome

The Treaty spells out an elaborate arrangement of technical, economic, and political intricacy. A boycott of international aid for apartheid South Africa required that the project be financed, and managed, in sections. The water transfer component was entirely financed by South Africa, which would also make payments for the water that would be delivered. The hydropower and development components were undertaken by Lesotho, which received international aid from a variety of donor agencies, particularly the World Bank. Phase IA of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project was completed in 1998, at a cost of $2.4 billion. Phase IB of the project was completed in early 2004, as a cost of approximately $1.5 billion.

The 1986 treaty provided for the construction of additional Phases: II-IV. However, changes in the projection of water demand in South Africa, along with concerns over negative social and environmental impacts of the project, have lead to negotiations on the future phases. In 2004 a feasibility study of Phase 2 began between the nations of South Africa and Lesotho.

Although Environmental Action Plans (EAPs) were carried out for both Phases IA and IB, EAPs for Phase IA were carried out while construction for the phase was already underway. It was in the course of Phase IB EAPs in 1994 that the need for an instream flow requirement became apparent. After studies of the biophysical, social and economic effects of the project were carried out, an Instream Flow Requirement (IFR) policy was implemented in 2002. In particular, river reaches and communities downstream of the project sites were considered in the assessment, whereas EAPs of Phase I considered only those areas only upstream of the project sites.

Issues and Stakeholders

Negotiating technical and financial details of water transfer from Lesotho to South Africa.

NSPD: Water Quantity, Governance, Assets

Stakeholder Types: Sovereign state/national/federal government, Non-legislative governmental agency, Industry/Corporate Interest

Lesotho, completely surrounded by South Africa, is a state poor in most natural resources, water being the exception. The industrial hub of South Africa, from Pretoria to Witwatersrand, has been exploiting most of the local water resources for years and the South African government has been in search of alternate sources. The elaborate technical and financial arrangements that led to construction of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) provide a good example of the possible gains of an integrative arrangement including a diverse "basket" of benefits.

Stakeholders:

- Lesotho

- South Africa

- World Bank

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:Lessons Learned in Lesotho HIghlands Water Project

Contributed by: Aaron T. Wolf, Joshua T. Newton, Matthew Pritchard (last edit: 12 February 2013)

Key Questions

Influence Leadership and Power: How does asymmetry of power influence water negotiations and how can the negative effects be mitigated?

Even with power disparity, there is possibility for agreement over water resources through economic benefits. South Africa is a much more powerful nation than Lesotho, but Lesotho has abundant water resources, which, through the Highlands Project, will benefit both nations economically and through the provision of water to South Africa. It is possible even when there is such a wide gap between nations in terms of power, to collaborate for the mutual gain of both countries.

Hydropower Dams and Large Storage Infrastructure: Where does the benefit “flow” from a hydropower project and how does that affect implementation and sustainability of the project?

It is more economically sound to begin impact studies before nations start to construct projects. It was shown through the Lesotho Highlands Water Project that if impact studies are started after the initiation of a major hydro-project, the costs for the project go up as necessary components for the project may not have been considered pre-study. For the Phase II of the LHWP, studies are being conducted to judge the feasibility of a project that was designed more than 15 years to ago to investigate in a more comprehensive manner the possible impacts of the project.

Transboundary Water Issues: What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution?

Renegotiation clauses in an agreement can prevent issues from arising for the nations involved. The LHWP treaty also exemplifies the importance of providing for renegotiation of project terms. In the absence of such a provision, the additional phases of the project might have been implemented without adequate consideration of their feasibility.

External Links

- Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) (2012). Oregon State University. Lesotho Highlands Project — The Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database (TFDD) This website is used to aid in the assessment of the process of water conflict prevention and resolution. Over the years we have developed this Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, a project of the Oregon State University Department of Geosciences, in collaboration with the Northwest Alliance for Computational Science and Engineering.

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at:http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/Lesotho_Highlands_New.htm