Organization for the Development of the Senegal River

| Geolocation: | 16° 30' 52.3307", -14° 44' 33.8392" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | 5,597,6005,597,600,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 434,518434,518 km² 167,767.4 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Moist tropical (Köppen A-type), Semi-arid/steppe (Köppen B-type), Moist, Monsoon |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, rangeland |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Hydropower Generation |

| Water Features: | Senegal River |

| Water Projects: | Manantali Dam |

Contents

Summary

The Senegal River, the second-largest river in Western Africa, originates in the Fouta Djallon Mountains of Guinea where its three main tributaries, the Bafing, Bakoye, and Faleme contribute 80% of the river's flow. After originating in Guinea, the Senegal River then travels 1,800 km crossing Mali, Mauritania and Senegal on its way to the Atlantic Ocean. [1]Following the independence of the basin countries, tension remained in the region due to the instability of the political powers and the influence of neo-colonial states such as the United States and the Soviet Union. Throughout the turmoil following World War II into the 1970s, the Senegal River continued to be a common link between the basin countries. There was a desire between them to cooperate in the management of the basin so that all countries would benefit from its development. This aspiration has been carried into the twenty-first century as Guinea, Mali, Mauritania and Senegal work cooperatively toward more effective basin management. The history of cooperation over this river basin has led to numerous multilateral agreements, projects and organizations over the last 25 years. The Manantali Dam has been working at full capacity since May 2003 providing each of the basin countries with electricity based on the amount the invested in the dam project.The Senegal River Charter, signed in 2002, sets the principles and procedures for allocating water between the various use sectors, defines procedures for the examination and acceptance of new water use projects, determines regulations for environmental preservation and protection and defines the framework and procedures for water user participation in resource management decision-making bodies.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

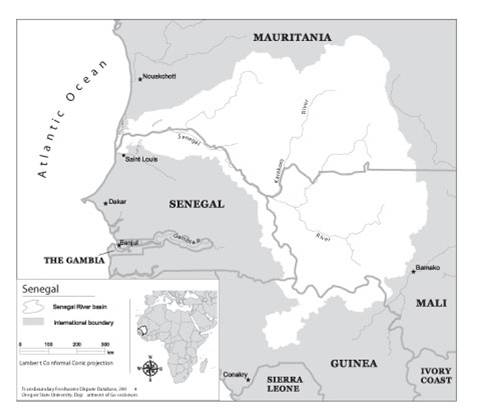

Image 1. Map of the Senegal River Basin.[2]

Image 1. Map of the Senegal River Basin.[2]

Background

The Senegal River, the second-largest river in Western Africa, originates in the Fouta Djallon Mountains of Guinea where its three main tributaries, the Bafing, Bakoye, and Faleme contribute 80% of the river's flow. After originating in Guinea, the Senegal River then travels 1,800 km crossing Mali, Mauritania and Senegal on its way to the Atlantic Ocean.

Following the independence of the basin countries, tension remained in the region due to the instability of the political powers and the influence of neo-colonial states such as the United States and the Soviet Union. Throughout the turmoil following World War II into the 1970s, the Senegal River continued to be a common link between the basin countries. There was a desire between them to cooperate in the management of the basin so that all countries would benefit from its development. This aspiration has been carried into the twenty-first century as Guinea, Mali, Mauritania and Senegal work cooperatively toward more effective basin management.

The river is a key resource for all three countries. Large herds of cattle, camels, goats and sheep migrate season to season across these borders and herders rely on this water source to sustain their herds. The basin region receives only an average of 660mm of rainfall per year, therefore the Senegal river waters represent the key to agriculture in the region. On the left bank, the surface area of community-based irrigated fields grew from 20 hectares in 1974 to 7,335 hectares in 1983 and 12,978 hectares in 1986. After agriculture, fishing is the largest economic activity in the region. Other river based economic activities include sugar cane production, rice framing and, to a lesser extent, mining,

Two dams, Manantali and Diama, were built in 1986 and 1988, respectively, in order to provide fresh water for agriculture and municipal uses and, in the case of the Manantali Dam, eventually to produce hydroelectric power for the region. These two dams were part of an economic growth strategy for the region that would reduce the investment risk and reduce poverty by increasing income-generating activities. The Manantali Dam was put on line in 2002 and is now supplying the three basin countries with 547 gwh/yr.

The Problem

There are a few areas of concern in regards to the Senegal River basin. The first is that of the climate. Beginning in the 1960s, the region suffered a continuous drop in rainfall until the mid-1980s. Because of the local populations' dependence on rainfall for crops, the droughts caused severe disruption in the economies of the basin states. The impacts to the economy were a result of the affects of the drought on the environment. Erosion, saltwater intrusion, drop in groundwater, vegetation loss among other impacts were felt in the entire region resulting in the exodus of large numbers of inhabitants from the rural areas towards the cities. The extreme poverty in the region makes these populations very vulnerable to changes in the climate.

In the 1960s and 1970s this problem led the countries of the Senegal River basin to look at ways to work together to mitigate the disastrous affects of severe droughts. Unlike other international water bodies, cooperation over this basin did not grow out of a conflict over use of the Senegal River resources. Instead the catalyst for cooperation was the vulnerability of the populations of the basin states. These four countries believe that collaboration on the development of this resource would improve the standard of living of all involved.

Problems in the basin today focus on the detrimental health and environmental and agricultural impacts of the two dams. Seasonal flooding and water movement decreased dramatically after the dams were built. This has caused an increase in the incidence of numerous waterborne diseases: diarrhea, schistosomiasis and malaria. The reduction of flooding also prevents pollution from industrial agricultural from flushing out of the basin. The dams have caused a reduction in pastureland, degradation of river fisheries, increased soil salinity and riverbank erosion. Traditional agricultural and pastoral productions systems have been superceded by irrigated, in some cases industrial size, agriculture. This emphasis on irrigation has created problems for social cohesion and access to land in some areas of the river basin, and in some cases artificial flooding has been so poorly planned that it has wiped out crops.

The basin countries expected to see a decrease in the rural-urban drift once irrigation was more feasible, but this has not happened. Politics also play an important role in decisions regarding the yearly artificial flood levels; they often vary according to the policies of current basin country governments.[3]

A separate, but equally worrisome issue is the pressure on this resource from a rapidly increasing river basin population: 16% of the population of the three river basin countries- Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal -live in this basin, and this population is growing at a rate of 3% per year.

Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

Individuals may add their own Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight (ASI) to a case. ASI sub-articles are protected, so that each contributor retains authorship and control of their own content. Edit the case to add your own ASI.

Learn moreASI:Organization for the Development of the Senegal River: Insights from the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database

Contributed by: Aaron T. Wolf, Joshua T. Newton, Matthew Pritchard (last edit: 12 February 2013)

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at: http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/OMVS_New.htm

- ^ Product of the Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University. Additional information about the TFDD can be found at:http://www.transboundarywaters.orst.edu/research/case_studies/OMVS_New.htm

- ^ Organization for the Development of the Senegal River (1972). Senegal River Basin, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, Pilot Case Studies, A Focus on Real-World Examples, pp. 448-461.