Difference between revisions of "Forming Groundwater Sustainability Agencies for Sonoma County"

| [unchecked revision] | [checked revision] |

SamKumasaka (Talk | contribs) m (Saved using "Save and continue" button in form) |

SamKumasaka (Talk | contribs) m (Saved using "Save and continue" button in form) |

||

| (19 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|Issue Description=Securing a steady supply of clean groundwater is in the interest of many types of stakeholders in Sonoma County sub-basins. | |Issue Description=Securing a steady supply of clean groundwater is in the interest of many types of stakeholders in Sonoma County sub-basins. | ||

| − | '''Affordable housing advocates:''' ensure water supply is adequate to provide for housing | + | '''Affordable housing advocates:''' ensure water supply is adequate to provide for housing<br /> |

| − | '''Agricultural interests:''' provide water for agricultural operations to support the local economy | + | '''Agricultural interests:''' provide water for agricultural operations to support the local economy<br /> |

| − | '''Community or organized citizens:''' provide water for the economy and citizens | + | '''Community or organized citizens:''' provide water for the economy and citizens<br /> |

| − | '''Environmental non-governmental organizations:''' provide water for people and ecosystems, fish and wildlife | + | '''Environmental non-governmental organizations:''' provide water for people and ecosystems, fish and wildlife; provide opportunity for groundwater recharge<br /> |

| − | '''Existing agencies:''' continue to manage water effectively and provide quality water supply for customers | + | '''Existing agencies:''' continue to manage water effectively and provide quality water supply for customers<br /> |

| − | '''GSA-eligible agencies:''' Most rely on groundwater for peak supply and emergencies. One city, Rohnert Park relies on groundwater as part of its regular supply. | + | '''GSA-eligible agencies:''' Most rely on groundwater for peak supply and emergencies. One city, Rohnert Park relies on groundwater as part of its regular supply.<br /> |

| − | '''Land use non-governmental organizations:''' connect land use planning to water resources planning to protect recharge areas and open space and concentrating housing in developed areas | + | '''Land use non-governmental organizations:''' connect land use planning to water resources planning to protect recharge areas and open space and concentrating housing in developed areas<br /> |

| − | '''Local government:''' manage the water supply to provide water for citizens and the economy | + | '''Local government:''' manage the water supply to provide water for citizens and the economy<br /> |

| − | '''Public utilities/regulated water companies''': private water companies that draw water from wells and provide water to urban customers | + | '''Public utilities/regulated water companies''': private water companies that draw water from wells and provide water to urban customers want to continue to provide water supply for customers<br /> |

| − | '''Public water systems:''' provide water to customers and ensure water quality is upheld | + | '''Public water systems:''' provide water to customers and ensure water quality is upheld<br /> |

| − | '''Rural residential well owners:''' have access to quality, affordable drinking water in wells | + | '''Rural residential well owners:''' have access to quality, affordable drinking water in wells<br /> |

'''Tribal government:''' Lytton Rancheria and Graton Rancheria rely on groundwater for their rancheria and casino operations. The Dry Creek Tribe owns land in the Petaluma Valley groundwater basin; however, the land is not currently in trust. | '''Tribal government:''' Lytton Rancheria and Graton Rancheria rely on groundwater for their rancheria and casino operations. The Dry Creek Tribe owns land in the Petaluma Valley groundwater basin; however, the land is not currently in trust. | ||

|NSPD=Water Quantity; Water Quality; Ecosystems; Governance; Assets | |NSPD=Water Quantity; Water Quality; Ecosystems; Governance; Assets | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

|Subject=Integration across Sectors | |Subject=Integration across Sectors | ||

|Key Question - Industries=How can consultation and cooperation among stakeholders and development partners be better facilitated/managed/fostered? | |Key Question - Industries=How can consultation and cooperation among stakeholders and development partners be better facilitated/managed/fostered? | ||

| + | |Key Question Description='''Key Tools and Frameworks''' | ||

| + | The key tools that were essential to success in this process were the stakeholder issue assessment, stakeholder identification, collaborative problem solving, interest-based negotiation, professional mediation, and transparency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The stakeholder issue assessment was critical for defining the issues and concerns, identifying stakeholders to represent the key interests, and designing a process that was responsive to political dynamics and the task at hand. The impartial mediation and facilitation team was able to make recommendations on the process for going forward. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Collaborative problem solving framework including interest-based negotiation were critical to this process. The process design focused on educating participants about the law and its requirements, and agencies informing one another about their stakeholders' interests. Understanding each other's’ interests was necessary so participants could craft solutions that were responsive to the range of interests engaged in the process. The participants used interest-based negotiation to identify and evaluate solutions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Professional mediators played an instrumental role in bringing agency stakeholders together and assisting with negotiations. The mediators created a process structure in which the parties were able to engage productively and consider outcomes that considered all the perspectives being shared. Amongst other outcomes, this resulted in Advisory Boards for each GSA where agricultural, rural, and environmental interests are represented and can oversee the process of achieving long-run groundwater sustainability. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Transparency was another important element of success. The mediators also worked to engage the broader public along the way, scheduling groundwater stakeholder forum meetings for the public and preparing communication materials on the web site and for work group members to share with constituents. The communication tools helped to engage the broader community, raising awareness and creating widespread support. All meetings were open to the public. A website ([http://sonomacountygroundwater.org/ sonomacountygroundwater.org]) continues to document ongoing progress by each GSA and provides notifications about prior and upcoming meetings. | ||

}} | }} | ||

|Water Feature={{Link Water Feature | |Water Feature={{Link Water Feature | ||

| Line 48: | Line 58: | ||

=== Regional Outline === | === Regional Outline === | ||

==== Geography ==== | ==== Geography ==== | ||

| + | Sonoma County lies in the North Coast Ranges of California, northwest of the San Francisco Bay Area region. | ||

| + | [[File:CASonoma.png|400px|thumbnail|right|California Water Projects with Sonoma County Overlay, California Water Plan]] | ||

==== Economy and Groundwater ==== | ==== Economy and Groundwater ==== | ||

| − | California is the most populous state in the country with almost 40 million residents and has the single largest state economy with a GDP of 2.67 trillion USD. This means it makes up 14.1% of US GDP, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis | + | California is the most populous state in the country with almost 40 million residents and has the single largest state economy with a GDP of 2.67 trillion USD. This means it makes up 14.1% of US GDP, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2017). Access to a water supply has been essential to the functioning of many of key state industries as well as its populous urban centers. California also has an extremely variable climate: dry years were common throughout the 20th century and could extend into a period of several years, such as the eight-year drought of Water Years (WY) 1984 to 1991 (DWR 2015; Chap. 3). During these extended dry periods, state agencies restricted water allocations to urban and agricultural water contractors and were forced to rely heavily on groundwater access, reservoir storage, and water sharing schemes. |

| − | California ranks as the leading agricultural state in the United States in terms of farm-level sales. In 2012, California’s farm-level sales totaled nearly $45 billion and accounted for 11% of total U.S. agricultural sales. Given frequent drought conditions in California, there has been much attention on the use of water to grow agricultural crops in the state. Depending on the data source, irrigated agriculture accounts for roughly 40% to 80% of total water supplies. Such discrepancies are largely based on different survey methods and assumptions, including the baseline amount of water estimated for use (e.g., what constitutes “available” supplies). The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimates water use for agricultural irrigation in California at 25.8 million acre-feet (MAF), accounting for 61% of USGS’s estimates of total withdrawals for the state | + | California ranks as the leading agricultural state in the United States in terms of farm-level sales. In 2012, California’s farm-level sales totaled nearly $45 billion and accounted for 11% of total U.S. agricultural sales (Johnson & Cody 2015). Given frequent drought conditions in California, there has been much attention on the use of water to grow agricultural crops in the state. Depending on the data source, irrigated agriculture accounts for roughly 40% to 80% of total water supplies (Johnson & Cody 2015). Such discrepancies are largely based on different survey methods and assumptions, including the baseline amount of water estimated for use (e.g., what constitutes “available” supplies). The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimates water use for agricultural irrigation in California at 25.8 million acre-feet (MAF), accounting for 61% of USGS’s estimates of total withdrawals for the state (Maupin et al. 2014). |

| − | USDA’s 2013 Farm and Ranch Irrigation Survey reports that, nationally, California has the largest number of irrigated farmed acres compared to other states and accounts for about one- fourth of total applied acre-feet of irrigated water in the United States. Of the reported 7.9 million irrigated acres in California, nearly 4 million acres were irrigated with groundwater from wells and about 1.0 million acres were irrigated with on-farm surface water supplies. Water use per acre in California is also high compared to other states averaging 3.1 acre-feet per acre, nearly twice the national average (1.6 acre-feet per acre) in 2013. Available data for | + | USDA’s 2013 Farm and Ranch Irrigation Survey reports that, nationally, California has the largest number of irrigated farmed acres compared to other states and accounts for about one-fourth of total applied acre-feet of irrigated water in the United States. Of the reported 7.9 million irrigated acres in California, nearly 4 million acres were irrigated with groundwater from wells and about 1.0 million acres were irrigated with on-farm surface water supplies (USDA 2013). Water use per acre in California is also high compared to other states averaging 3.1 acre-feet per acre, nearly twice the national average (1.6 acre-feet per acre) in 2013 (USDA 2013). Available data for that year indicates, of total irrigated acres harvested in California, about 31% of irrigated acres were land in orchards and 18% were land in vegetables (USDA 2013). Another 46% of irrigated acres harvested were land in alfalfa, hay, pastureland, rice, corn, and cotton (USDA 2013). |

==== Climate and Groundwater ==== | ==== Climate and Groundwater ==== | ||

| − | Drought periods are a trend which will increase in frequency and severity as a result of anthropogenic climate change: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that precipitation events, especially snowfall, in the southwestern United States will become less frequent or productive in the future. These changes in surface water availability may further increase the role of groundwater in California’s future water budget: historically, California has | + | Drought periods are a trend which will increase in frequency and severity as a result of anthropogenic climate change: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that precipitation events, especially snowfall, in the southwestern United States will become less frequent or productive in the future (Kunkel et al. 2013). These changes in surface water availability may further increase the role of groundwater in California’s future water budget: historically, California has relied on groundwater to supplement other backstops like reservoirs. Therefore, the California Water Plan emphasizes that the protection of groundwater aquifers and proper management of contaminated aquifers is critical to ensure that this resource can maintain its multiple beneficial uses (California Water Plan 2013). |

| + | |||

| + | The California Department of Public Health estimates that 85 percent of California’s community water systems serve more than 30 million people who rely on groundwater for a portion of their drinking water supply (California Water Boards 2013; 7). Because of significant current and future reliance on groundwater in some regions of California, contamination or overdraft of groundwater aquifers has far-reaching consequences for municipal and agricultural water supplies. Sonoma County is a groundwater-dependent area, regularly drawing more than 70 percent of its water from wells to meet demand for 260 million gallons a day, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Agriculture consumes nearly 150 million gallons, about 60 percent of the total. California’s reliance on groundwater increases during times of drought, offsetting surface water demand from municipal, agricultural, and industrial sources. | ||

| − | + | A 2014 Stanford "Water in the West" study summarizes the often-overlooked impacts of groundwater overdraft. Direct impacts include a “reduced water supply due to aquifer depletion or groundwater contamination, increased groundwater pumping costs, and the costs of well replacement or deepening” (Moran et al. 2014). Less obvious are the indirect consequences of groundwater overdraft, which include “land subsidence and infrastructure damage, harm to groundwater-dependent ecosystems, and the economic losses from a more unreliable water supply for California” (Moran et al. 2014). In coastal groundwater basins, overdraft of aquifers can result in seawater being drawn in. This saltwater intrusion contaminates the water supply and requires expensive remediation. Groundwater overdraft can also lead to diminished surface water flow (affecting ecosystem services), degraded water quality and attendant health problems, and increased food prices. | |

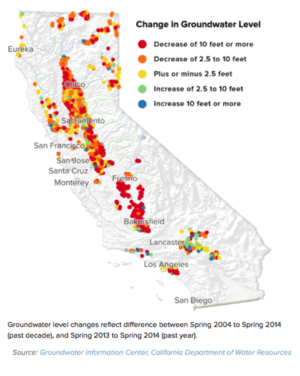

| − | + | [[File:sal2.png|300px|thumbnail|right|10-Year Change in Groundwater Level (2004-2014)|]] | |

| − | Although there is little data available on total damages, costs associated with overdraft mount in a variety of ways, some more obvious and immediate than others. Accessing deeper and deeper aquifers is costly because drilling and pumping groundwater are expensive. The electricity needed to run pumps is a significant and obvious expense: in 2014, the statewide drought is estimated to have cost the agricultural industry $454 million in additional pumping costs alone. Remediation of water quality and land subsidence is an endeavor where costs accumulate over time. Local water agencies must undertake dramatic measures to stem saltwater intrusion into aquifers, like running pipes from distant surface water sources to inject into the ground. Land is subsiding at more than a foot a year in some parts of the state as a result of groundwater overdraft and aquifer compaction. In some California valleys like San Joaquin, well over a billion dollars of associated damages have accumulated over several decades as land buckles under infrastructure and buildings | + | Although there is little data available on total damages, costs associated with overdraft mount in a variety of ways, some more obvious and immediate than others. Accessing deeper and deeper aquifers is costly because drilling and pumping groundwater are expensive. The electricity needed to run pumps is a significant and obvious expense: in 2014, the statewide drought is estimated to have cost the agricultural industry $454 million in additional pumping costs alone (Moran et al. 2014). Remediation of water quality and land subsidence is an endeavor where costs accumulate over time. Local water agencies must undertake dramatic measures to stem saltwater intrusion into aquifers, like running pipes from distant surface water sources to inject into the ground. Land is subsiding at more than a foot a year in some parts of the state as a result of groundwater overdraft and aquifer compaction. In some California valleys like San Joaquin, well over a billion dollars of associated damages have accumulated over several decades as land buckles under infrastructure and buildings (Moran et al. 2014). Rural landowners and small-scale farmers can be disproportionately affected by overdraft as they have less financial capital to dig new or deeper wells (Richtel 2015). |

=== Politics and Governance === | === Politics and Governance === | ||

==== Groundwater Management Act ==== | ==== Groundwater Management Act ==== | ||

| − | Since the early 1990s, existing local agencies have developed, implemented, and updated more than 125 Groundwater Management Plans (GWMP) using the systematic procedure provided by the Groundwater Management Act, Sections 10750‐10755 of the California Water Code (commonly referred to as AB 3030). AB 3030 allowed certain defined existing local agencies to develop a groundwater management plan in groundwater basins defined in California Department of Water Resources (DWR) | + | Since the early 1990s, existing local agencies have developed, implemented, and updated more than 125 [http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/groundwater_management/GWM_Plans_inCA.cfm Groundwater Management Plans (GWMP)] using the systematic procedure provided by the Groundwater Management Act, Sections 10750‐10755 of the California Water Code (commonly referred to as AB 3030). AB 3030 allowed certain defined existing local agencies to develop a groundwater management plan in groundwater basins defined in California Department of Water Resources (DWR) [http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/bulletin118/index.cfm Bulletin 118]. |

The twelve potential components of a Groundwater Management Plan, as listed in Water Code Section 10753.8, include: | The twelve potential components of a Groundwater Management Plan, as listed in Water Code Section 10753.8, include: | ||

| Line 82: | Line 96: | ||

* Development of relationships with state and federal regulatory agencies. | * Development of relationships with state and federal regulatory agencies. | ||

* Review of land use plans and coordination with land use planning agencies to assess activities which create a reasonable risk of groundwater contamination. | * Review of land use plans and coordination with land use planning agencies to assess activities which create a reasonable risk of groundwater contamination. | ||

| − | [http://www.water.ca.gov/urbanwatermanagement/2010uwmps/CA%20Water%20Service%20Co%20-%20Salinas/Appendix%20H%20-%20GWMP.pdf; | + | ([http://www.water.ca.gov/urbanwatermanagement/2010uwmps/CA%20Water%20Service%20Co%20-%20Salinas/Appendix%20H%20-%20GWMP.pdf Monterey County GWMP 2006]; 1) |

However, under the previous law (AB3030), no new level of government is formed and action by the agency is voluntary, not mandatory. Senate Bill 1938 enhanced the process slightly and added technical components that are required in each plan in order to be eligible for groundwater related DWR grant funding. | However, under the previous law (AB3030), no new level of government is formed and action by the agency is voluntary, not mandatory. Senate Bill 1938 enhanced the process slightly and added technical components that are required in each plan in order to be eligible for groundwater related DWR grant funding. | ||

| − | Assembly Bill 359, signed into Water Code 2011, added further technical components and modified several groundwater management plan adoption procedures. GWMPs were not required to be submitted to the California DWR under the Groundwater Management Act. AB 359 placed new requirements on agencies concerning the submittal of GWMP documents and on DWR to provide public access to this information. GWMPs may still be developed in low-priority basins as they are not subject to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). | + | [http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/docs/2011_AB359_Summary_02192014.pdf Assembly Bill 359], signed into Water Code 2011, added further technical components and modified several groundwater management plan adoption procedures. GWMPs were not required to be submitted to the California DWR under the Groundwater Management Act. AB 359 placed new requirements on agencies concerning the submittal of GWMP documents and on DWR to provide public access to this information. GWMPs may still be developed in low-priority basins as they are not subject to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). |

| − | + | ||

==== Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (2014) ==== | ==== Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (2014) ==== | ||

California’s historic groundwater management legislation, passed in 2014 after the driest three-year period recorded in state history, requires that groundwater be managed locally to ensure a sustainable resource well into the future. This legislation, a package of three bills (AB 1739, SB 1168, and SB 1319) known as the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), prioritizes groundwater basins in significant overdraft to move forward first. SGMA requires that such areas first identify or form an agency or group of agencies to oversee groundwater management, then develop a plan to to halt overdraft and bring basins into balanced levels of pumping and recharge by 2020 or 2022, depending on water supply condition. Beginning January 1, 2015, no Groundwater Management Plans can be adopted in medium- and high-priority basins in accordance with the SGMA. Existing GWMPs will be in effect until Groundwater Sustainability Plans (GSPs) are adopted in medium- and high-priority basins. | California’s historic groundwater management legislation, passed in 2014 after the driest three-year period recorded in state history, requires that groundwater be managed locally to ensure a sustainable resource well into the future. This legislation, a package of three bills (AB 1739, SB 1168, and SB 1319) known as the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), prioritizes groundwater basins in significant overdraft to move forward first. SGMA requires that such areas first identify or form an agency or group of agencies to oversee groundwater management, then develop a plan to to halt overdraft and bring basins into balanced levels of pumping and recharge by 2020 or 2022, depending on water supply condition. Beginning January 1, 2015, no Groundwater Management Plans can be adopted in medium- and high-priority basins in accordance with the SGMA. Existing GWMPs will be in effect until Groundwater Sustainability Plans (GSPs) are adopted in medium- and high-priority basins. | ||

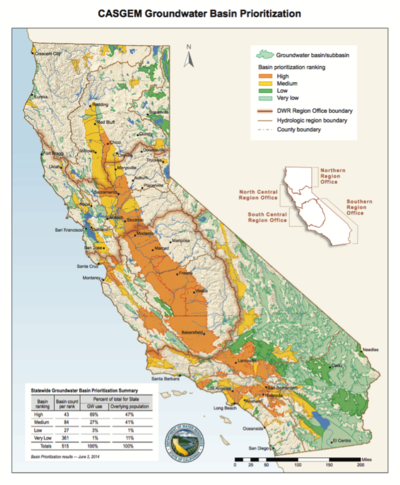

| − | For the first time in California history, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act provides local agencies with a framework for local, sustainable management of groundwater basins. The State has designated 127 basins in the state as high- or medium-priority based on population, irrigated acreage, public supply well distribution, and other variables. Prioritized basins, which includes the three Sonoma Valley sub-basins, must create groundwater sustainability plans by 2022. The California Department of Water Resources Bulletin 118 is a report that defines the basin boundaries. | + | For the first time in California history, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act provides local agencies with a framework for local, sustainable management of groundwater basins. The State of California has designated 127 basins in the state as high- or medium-priority based on population, irrigated acreage, public supply well distribution, and other variables. Prioritized basins, which includes the three Sonoma Valley sub-basins, must create groundwater sustainability plans by 2022. The California Department of Water Resources Bulletin 118 is a report that defines the basin boundaries. |

Basins that must comply with SGMA have to meet several critical deadlines. A local agency, combination of local agencies, or county must establish a Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) by June 30, 2017. Local agencies with water supply, water management, or land use responsibilities are eligible to form GSAs. A water corporation regulated by the Public Utilities Commission or a mutual water company may participate in a groundwater sustainability agency through a memorandum of agreement or other legal agreement. The GSA is responsible for developing and implementing a groundwater sustainability plan that considers all beneficial uses and users of groundwater in the basin. | Basins that must comply with SGMA have to meet several critical deadlines. A local agency, combination of local agencies, or county must establish a Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) by June 30, 2017. Local agencies with water supply, water management, or land use responsibilities are eligible to form GSAs. A water corporation regulated by the Public Utilities Commission or a mutual water company may participate in a groundwater sustainability agency through a memorandum of agreement or other legal agreement. The GSA is responsible for developing and implementing a groundwater sustainability plan that considers all beneficial uses and users of groundwater in the basin. | ||

| Line 105: | Line 118: | ||

== Background on Sonoma County Groundwater == | == Background on Sonoma County Groundwater == | ||

| − | Sonoma County has three priority basins subject to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. This case study is focusing on the Santa Rosa Plan. Two other basins, the Petaluma Valley and the Sonoma Valley formed GSAs at the same time. All three basins developed a very similar structure, with a governing board made up of representatives of GSA-eligible entities and an advisory board made up of the key interests in the basin. This case study focuses on the conditions, process, and agreements in the Santa Rosa Plain. | + | Sonoma County has three priority basins subject to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (CASGEM). This case study is focusing on the Santa Rosa Plan. Two other basins, the Petaluma Valley and the Sonoma Valley formed GSAs at the same time. All three basins developed a very similar structure, with a governing board made up of representatives of GSA-eligible entities and an advisory board made up of the key interests in the basin. This case study focuses on the conditions, process, and agreements in the Santa Rosa Plain. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[File:SonomaBasins.png|400px|thumbnail|right|SGMA Basin Boundary Map|]] | |

=== Existing Management Programs === | === Existing Management Programs === | ||

| Line 119: | Line 132: | ||

The Santa Rosa Plain Groundwater Management Plan (Plan) was developed through the collaborative and cooperative effort of a broadly based, 30- member Basin Advisory Panel. The Plan is intended to inform and guide local decisions about groundwater management in the Santa Rosa Plain Watershed. Its purpose is to proactively coordinate public and private groundwater management efforts and leverage funding opportunities to maintain a sustainable, locally-managed, high-quality groundwater resource for current and future users while sustaining natural groundwater and surface water functions. | The Santa Rosa Plain Groundwater Management Plan (Plan) was developed through the collaborative and cooperative effort of a broadly based, 30- member Basin Advisory Panel. The Plan is intended to inform and guide local decisions about groundwater management in the Santa Rosa Plain Watershed. Its purpose is to proactively coordinate public and private groundwater management efforts and leverage funding opportunities to maintain a sustainable, locally-managed, high-quality groundwater resource for current and future users while sustaining natural groundwater and surface water functions. | ||

| − | The United States Geological Survey (USGS) has completed a study of the Santa Rosa Plain groundwater basin in collaboration with the Sonoma County Water Agency (Water Agency), the cities of Cotati, Rohnert Park, Santa Rosa and Sebastopol, the town of Windsor, the County of Sonoma, and the California American Water Company. As part of this study, the USGS developed an innovative computer model that fully integrates surface water and groundwater to better understand and manage the Santa Rosa Plain’s water resources. The study shows that increased groundwater pumping has caused an imbalance of groundwater inflow and outflow. This imbalance could affect wells and eventually will likely reduce flows in creeks and streams, leading to a potential for decline in habitat and ecosystems. Rural pumping for residences and agricultural water supply traditionally account for the majority of groundwater withdrawals, and both these categories increased over the 1976- 2010 study period. | + | The United States Geological Survey (USGS) has completed a study of the Santa Rosa Plain groundwater basin in collaboration with the Sonoma County Water Agency (Water Agency), the cities of Cotati, Rohnert Park, Santa Rosa and Sebastopol, the town of Windsor, the County of Sonoma, and the California American Water Company. As part of this study, the USGS developed an innovative computer model that fully integrates surface water and groundwater to better understand and manage the Santa Rosa Plain’s water resources. The study shows that increased groundwater pumping has caused an imbalance of groundwater inflow and outflow. This imbalance could affect wells and eventually will likely reduce flows in creeks and streams, leading to a potential for decline in habitat and ecosystems. Rural pumping for residences and agricultural water supply traditionally account for the majority of groundwater withdrawals, and both these categories increased over the 1976 - 2010 study period. |

| − | Groundwater pumping by public water suppliers in the Plan area (e.g. Water Agency and cities) generally increased until 2001 but subsequently declined. The USGS model shows decreased groundwater levels in response to pumping, which reduced groundwater contribution to stream flow, groundwater uptake by plants (known as evapotranspiration), and groundwater storage. The model also simulates the effects of several potential climate change scenarios on surface water flows and groundwater supplies. The results indicate a potential for overall lowering of groundwater levels compared to historic baseline conditions; reduced groundwater contribution to stream flow (“baseflow”); reduced groundwater evapotranspiration in riparian areas and reduced groundwater flow to wetlands and springs; and more infiltration of surface water to groundwater, further reducing stream baseflow ( | + | Groundwater pumping by public water suppliers in the Plan area (e.g. Water Agency and cities) generally increased until 2001 but subsequently declined. The USGS model shows decreased groundwater levels in response to pumping, which reduced groundwater contribution to stream flow, groundwater uptake by plants (known as evapotranspiration), and groundwater storage. The model also simulates the effects of several potential climate change scenarios on surface water flows and groundwater supplies. The results indicate a potential for overall lowering of groundwater levels compared to historic baseline conditions; reduced groundwater contribution to stream flow (“baseflow”); reduced groundwater evapotranspiration in riparian areas and reduced groundwater flow to wetlands and springs; and more infiltration of surface water to groundwater, further reducing stream baseflow ([http://www.scwa.ca.gov/files/docs/projects/srgw/SRP_GMP_12-14.pdf Santa Rosa Plain Groundwater Management Plan], 2014). |

Water supply in the Santa Rosa Plain either comes from a municipality (a city or other water provider) or a privately owned well. The water supplied by municipalities is usually a combination of surface water from the Russian River and local groundwater. Russian River water delivered by the Sonoma County Water Agency to many of the municipalities in the Santa Rosa Plain is sourced from outside of the Basin. In total (including water from municipalities and water from privately owned wells), it is estimated that a little over half of the water used in the Santa Rosa Plain is local groundwater. The use of recycled water for agricultural and landscape irrigation has also become an important source of water supply and can offset the need to use potable water supplies. | Water supply in the Santa Rosa Plain either comes from a municipality (a city or other water provider) or a privately owned well. The water supplied by municipalities is usually a combination of surface water from the Russian River and local groundwater. Russian River water delivered by the Sonoma County Water Agency to many of the municipalities in the Santa Rosa Plain is sourced from outside of the Basin. In total (including water from municipalities and water from privately owned wells), it is estimated that a little over half of the water used in the Santa Rosa Plain is local groundwater. The use of recycled water for agricultural and landscape irrigation has also become an important source of water supply and can offset the need to use potable water supplies. | ||

| Line 132: | Line 145: | ||

The State of California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014. The State has designated three groundwater basins in Sonoma County as medium priority: the Petaluma Valley, Santa Rosa Plain, and Sonoma Valley. The Act requires that medium and high priority basins form a groundwater sustainability agency by June 2017, develop a groundwater sustainability plan by 2022, and achieve sustainability by 2042. Under the Act, local agencies with water supply, water management or land use responsibilities are eligible to form a groundwater sustainability agency. To develop an effective process for groundwater sustainability agency formation in these three basins, the Sonoma County Water Agency contracted with the Consensus Building Institute to conduct a stakeholder assessment and make recommendations on a process for forming groundwater sustainability agencies in compliance with the Act. This section summarizes CBI’s interview findings and process recommendations for GSA formation. | The State of California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014. The State has designated three groundwater basins in Sonoma County as medium priority: the Petaluma Valley, Santa Rosa Plain, and Sonoma Valley. The Act requires that medium and high priority basins form a groundwater sustainability agency by June 2017, develop a groundwater sustainability plan by 2022, and achieve sustainability by 2042. Under the Act, local agencies with water supply, water management or land use responsibilities are eligible to form a groundwater sustainability agency. To develop an effective process for groundwater sustainability agency formation in these three basins, the Sonoma County Water Agency contracted with the Consensus Building Institute to conduct a stakeholder assessment and make recommendations on a process for forming groundwater sustainability agencies in compliance with the Act. This section summarizes CBI’s interview findings and process recommendations for GSA formation. | ||

| + | [[File:sal3.png|400px|thumbnail|left|CASGEM Groundwater Basin Prioritization|]] | ||

| + | |||

CBI conducted interviews with representatives of each GSA-eligible local agency and key organizations and interest groups. CBI also met with both the Santa Rosa Plain and the Sonoma Valley basin advisory panels in person to discuss panel members’ perspectives on implementing the Act. CBI also conducted an online survey related to these issues and received 36 confidential responses. For the survey, CBI invited basin advisory panel members from both the Sonoma Valley and Santa Rosa Plain, stakeholders interested in water issues, federal and state agencies with jurisdiction in the region, and Public Utilities Commission-regulated water companies to participate. | CBI conducted interviews with representatives of each GSA-eligible local agency and key organizations and interest groups. CBI also met with both the Santa Rosa Plain and the Sonoma Valley basin advisory panels in person to discuss panel members’ perspectives on implementing the Act. CBI also conducted an online survey related to these issues and received 36 confidential responses. For the survey, CBI invited basin advisory panel members from both the Sonoma Valley and Santa Rosa Plain, stakeholders interested in water issues, federal and state agencies with jurisdiction in the region, and Public Utilities Commission-regulated water companies to participate. | ||

| Line 148: | Line 163: | ||

In determining the composition of the GSA’s board of directors, stakeholders preferred to avoid using the quantity of water use as a determinant for representation because conserving water use should be a key value. Instead, they thought population should be a consideration in representation, as long as equity was also a consideration. Participants also thought allowing governing boards to appoint representatives (so a representative could be an elected official or an appointee) would be helpful as each entity could decide who represents it. However, interviewees also believed the GSA Board should not mix staff and elected officials. Interviewees preferred that GSA board consist of elected or appointees of electeds. Some would like opportunity for agriculture and private water companies (like Cal American Water) to have a role in governance, but there was also a concern that agricultural interests, if involved in GSA, might overwhelm cities’ interests. | In determining the composition of the GSA’s board of directors, stakeholders preferred to avoid using the quantity of water use as a determinant for representation because conserving water use should be a key value. Instead, they thought population should be a consideration in representation, as long as equity was also a consideration. Participants also thought allowing governing boards to appoint representatives (so a representative could be an elected official or an appointee) would be helpful as each entity could decide who represents it. However, interviewees also believed the GSA Board should not mix staff and elected officials. Interviewees preferred that GSA board consist of elected or appointees of electeds. Some would like opportunity for agriculture and private water companies (like Cal American Water) to have a role in governance, but there was also a concern that agricultural interests, if involved in GSA, might overwhelm cities’ interests. | ||

| − | Multiple interviewees suggested the Sonoma County Transportation Authority and the Sonoma County Water Agency’s Water Advisory Committee / Technical Advisory Committee as successful models to examine and possibly emulate. The latter was thought to be effective due to its policy arm that imposes limits and potential fees. In evaluating SCWA’s eligibility to become a GSA, interviewees noted that the agency has pumping facilities in the Santa Rosa Plain groundwater basin only, not in Petaluma Valley or Sonoma Valley. | + | Multiple interviewees suggested the Sonoma County Transportation Authority and the Sonoma County Water Agency’s Water Advisory Committee/Technical Advisory Committee as successful models to examine and possibly emulate. The latter was thought to be effective due to its policy arm that imposes limits and potential fees. In evaluating SCWA’s eligibility to become a GSA, interviewees noted that the agency has pumping facilities in the Santa Rosa Plain groundwater basin only, not in Petaluma Valley or Sonoma Valley. |

==== Potential Financial Structure ==== | ==== Potential Financial Structure ==== | ||

| − | Agency interviewees were concerned about costs and funding SGMA implementation. While SGMA authorizes the groundwater sustainability agency to levy fees, the agency is still subject to Proposition 218, potentially limiting the ability to raise funds. Proposition 218 is a California constitutional amendment passed in 1996 requiring voter approval prior to the imposition or increase of general taxes, assessment and other user fees by local government. | + | Agency interviewees were concerned about costs and funding SGMA implementation. While SGMA authorizes the groundwater sustainability agency to levy fees, the agency is still subject to Proposition 218, potentially limiting the ability to raise funds. [https://www.californiataxdata.com/pdf/Proposition218.pdf Proposition 218] is a California constitutional amendment passed in 1996 requiring voter approval prior to the imposition or increase of general taxes, assessment and other user fees by local government. |

| − | Entities that purchase water from the Sonoma County Water Agency (SCWA) to supply their customer base (water contractors) expressed concern about paying for groundwater planning more than once – through water purchases that fund SCWA and through cost sharing agreements for groundwater planning. The cities express commitment to continuing to fund groundwater planning, but would like other groundwater users (specifically in unincorporated areas) to contribute since substantial groundwater use occurs outside of city boundaries, and some cities only use groundwater for emergency and peak supply – it is a small part of their water budget. | + | Entities that purchase water from the Sonoma County Water Agency (SCWA) to supply their customer base (water contractors) expressed concern about paying for groundwater planning more than once – through water purchases that fund SCWA and through cost sharing agreements for groundwater planning. The cities express commitment to continuing to fund groundwater planning, but would like other groundwater users (specifically, in unincorporated areas) to contribute since substantial groundwater use occurs outside of city boundaries, and some cities only use groundwater for emergency and peak supply – it is a small part of their water budget. |

==== County of Sonoma Role ==== | ==== County of Sonoma Role ==== | ||

| Line 165: | Line 180: | ||

=== Governance Options === | === Governance Options === | ||

As part of the assessment, the facilitator and interviewees discussed possible configurations for the groundwater sustainability agency(s) within basins and across the three basins. Stakeholders articulated pros and cons of different options based on their understanding at the time. | As part of the assessment, the facilitator and interviewees discussed possible configurations for the groundwater sustainability agency(s) within basins and across the three basins. Stakeholders articulated pros and cons of different options based on their understanding at the time. | ||

| − | + | ||

'''One GSA per Basin or 3 GSAs''' | '''One GSA per Basin or 3 GSAs''' | ||

| + | |||

'''''Pros''''' | '''''Pros''''' | ||

| − | + Provides for decision making at local level, reflects each unique basin | + | * + Provides for decision making at local level, reflects each unique basin |

'''''Cons''''' | '''''Cons''''' | ||

| − | - GSAs might compete against one another for external funding | + | * - GSAs might compete against one another for external funding |

| − | - Spreading resources too thin | + | * - Spreading resources too thin |

| − | + | ||

''Models:'' Existing BAP Structure | ''Models:'' Existing BAP Structure | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

'''Hybrid: One GSA per Basin (or 3 GSAs) that Coordinate or Share Staff and Resources''' | '''Hybrid: One GSA per Basin (or 3 GSAs) that Coordinate or Share Staff and Resources''' | ||

| + | |||

This option was very popular among interviewees. | This option was very popular among interviewees. | ||

| + | |||

'''''Pros''''' | '''''Pros''''' | ||

| − | + Provides for decision making at local level | + | * + Provides for decision making at local level |

| − | + Shares resources across basins | + | * + Shares resources across basins |

| − | + Allows for regional consideration on management issues | + | * + Allows for regional consideration on management issues |

| − | + | ||

'''''Cons''''' | '''''Cons''''' | ||

| − | - GSAs might compete against one another for external funding | + | * - GSAs might compete against one another for external funding |

| − | + | ||

''Model:'' Metropolitan Transportation Commission | ''Model:'' Metropolitan Transportation Commission | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

'''Centralized: 1 GSA in County for all three Basins''' | '''Centralized: 1 GSA in County for all three Basins''' | ||

| + | |||

'''''Pros''''' | '''''Pros''''' | ||

| − | + Like the simplicity and ease of setting up | + | * + Like the simplicity and ease of setting up |

| − | + Shares decision making across agencies with possibility of designating seats for particular agencies or interests groups | + | * + Shares decision making across agencies with possibility of designating seats for particular agencies or interests groups |

| − | + Shares resources and costs | + | * + Shares resources and costs |

| − | + | ||

'''''Cons''''' | '''''Cons''''' | ||

| − | - Governing board too big. Agency too big. | + | * - Governing board too big. Agency too big. |

| − | - Prefer decision-making at local level. Might miss the nuances of the local detail | + | * - Prefer decision-making at local level. Might miss the nuances of the local detail |

| − | - Concerned about GSA board representing all groundwater users’ interests | + | * - Concerned about GSA board representing all groundwater users’ interests |

| − | + | ||

| − | '''Multiple GSAs/Basin''' | + | |

| + | '''Multiple GSAs/Basin'''<br /> | ||

No interviewees expressed interest in having multiple GSAs within a basin. | No interviewees expressed interest in having multiple GSAs within a basin. | ||

| Line 229: | Line 251: | ||

==== Desired Qualities of a Groundwater Sustainability Agency ==== | ==== Desired Qualities of a Groundwater Sustainability Agency ==== | ||

| − | In response to the facilitator’s question, respondents articulated that the agency or agencies should have political credibility and a strong technical capacity, with a track record of conducting similar activities. The agency should be willing to leverage existing work (USGS studies and existing Groundwater Management Programs) and link responsibility between countywide surface water supply and basin groundwater supplies. It should fairly represent local interests and have equal representation of those interests on its Board of Directors. Consistent with SGMA, participants would like to evaluate the ability of the governance structure to protect groundwater supply interests for all beneficial uses and users. Scalability was also an important long-term consideration: the agency should be structured so that it can manage future basin designations as medium or high priority in the county. | + | In response to the facilitator’s question, respondents articulated that the agency or agencies should have political credibility and a strong technical capacity, with a track record of conducting similar activities. The agency should be willing to leverage existing work (like USGS studies and existing Groundwater Management Programs) and link responsibility between countywide surface water supply and basin groundwater supplies. It should fairly represent local interests and have equal representation of those interests on its Board of Directors. Consistent with SGMA, participants would like to evaluate the ability of the governance structure to protect groundwater supply interests for all beneficial uses and users. Scalability was also an important long-term consideration: the agency should be structured so that it can manage future basin designations as medium or high priority in the county. |

| − | Interviewees recommended repeatedly to keep the structure as simple as possible and to avoid cumbersome, costly bureaucracy while allowing more complex structures to evolve if needed in the future. Concern exists that establishing structure could be lengthy or difficult. Some worry that creating a joint powers authority would be very difficult to organize / agree to and cumbersome in implementation. They advocated for a cost-effective and efficient institution that considers ratepayers when leveling self-sustaining fees. Interviewees recommend comparing costs, potential fees that structures and options would require. | + | Interviewees recommended repeatedly to keep the structure as simple as possible and to avoid cumbersome, costly bureaucracy while allowing more complex structures to evolve if needed in the future. Concern exists that establishing structure could be lengthy or difficult. Some worry that creating a joint powers authority would be very difficult to organize/agree to and cumbersome in implementation. They advocated for a cost-effective and efficient institution that considers ratepayers when leveling self-sustaining fees. Interviewees recommend comparing costs, potential fees that structures and options would require. |

Interviewees noted that SCWA has the technical and scientific capacity to develop the groundwater sustainability plan. SCWA is involved in groundwater management and conjunctive use. SCWA also provides regional perspective across basins and has been able to solicit funding from the state to assist existing groundwater programs. | Interviewees noted that SCWA has the technical and scientific capacity to develop the groundwater sustainability plan. SCWA is involved in groundwater management and conjunctive use. SCWA also provides regional perspective across basins and has been able to solicit funding from the state to assist existing groundwater programs. | ||

| Line 272: | Line 294: | ||

The first area that the group moved forward was these adopted principles. The principles served as a tool for staff to share with their elected boards of directors and the public about their goals and intent in the GSA formation process. | The first area that the group moved forward was these adopted principles. The principles served as a tool for staff to share with their elected boards of directors and the public about their goals and intent in the GSA formation process. | ||

| − | # | + | # Eligible local agencies should work together to identify a unified and equitable approach to governance in which each local agency has a meaningful voice. |

| − | # | + | # The governance structure should reinforce the “local management” principles embodied in the Act by ensuring that management decisions are made at the local level in each groundwater basin. |

| − | # | + | # While local management is essential, opportunities should be found for sharing resources and management expertise across basins. The governance structure should avoid redundancy and reduce management costs by efficiently using local staff and technical resources and agency infrastructure. |

# Groundwater sustainability planning under the Act should build upon successful water management efforts in Sonoma County, including the adopted groundwater management plans in the Sonoma Valley and Santa Rosa Plain. | # Groundwater sustainability planning under the Act should build upon successful water management efforts in Sonoma County, including the adopted groundwater management plans in the Sonoma Valley and Santa Rosa Plain. | ||

# In addition to the local agencies, community stakeholders should be represented through additional formal governance structures, such as advisory committees, to ensure diverse viewpoints are represented in plan development and implementation. | # In addition to the local agencies, community stakeholders should be represented through additional formal governance structures, such as advisory committees, to ensure diverse viewpoints are represented in plan development and implementation. | ||

| Line 293: | Line 315: | ||

=== Voting === | === Voting === | ||

| − | The governing board adopted a simple and super-majority voting structure and unanimous voting for financial contributions. | + | The governing board adopted a simple and super-majority voting structure and unanimous voting for financial contributions. To approve a measure, a simple-majority (>50% or 5 of 9 Directors) of Board Directors must vote in favor to approve the decision. All decision-making votes require a simple majority, except for those requiring super-majority or unanimous votes. A super-majority would require 75% of board directors for approval. This would be needed for fees, regulations, and budgets. |

| − | + | ||

| − | To approve a measure, a simple-majority (>50% or 5 of 9 Directors) of Board Directors must vote in favor to approve the decision. All decision-making votes require a simple majority, except for those requiring super-majority or unanimous votes. | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | A super-majority would require 75% of board directors for approval. This would be needed for fees, regulations, and budgets. | + | |

GSA Board unanimous voting would be required for financial contributions of entities that signed on to the legal agreement that created the structure, the joint powers authority. The rationale was that if an entity did not have the funds available, then the GSA could not levy fees for them. The alternative would be to modify the GSA budget. | GSA Board unanimous voting would be required for financial contributions of entities that signed on to the legal agreement that created the structure, the joint powers authority. The rationale was that if an entity did not have the funds available, then the GSA could not levy fees for them. The alternative would be to modify the GSA budget. | ||

=== Periodic Check-in on Governance === | === Periodic Check-in on Governance === | ||

| − | To ensure that agreement meets GSA needs, a public review will be held after initial fee study, after the Groundwater Sustainability Plan is adopted, and very 10 years after GSP adoption. | + | To ensure that the agreement meets GSA needs, a public review will be held after initial fee study, after the Groundwater Sustainability Plan is adopted, and very 10 years after GSP adoption. |

=== Strong Advisory Body === | === Strong Advisory Body === | ||

A strong advisory body was created to address stakeholder input in order to advise Sonoma Valley GSA Boards on plan development and implementation. Each advisory body plays a significant policy-making role, through providing recommendations to the GSA board on a broad array of issues, including the groundwater sustainability plan itself and how that plan would be implemented through regulations, projects, programs and funding. The Sonoma Advisory Body will advise the board on development and implementation of groundwater sustainability plan, regulations, fees, capital projects, programs, and community with stakeholder constituencies. | A strong advisory body was created to address stakeholder input in order to advise Sonoma Valley GSA Boards on plan development and implementation. Each advisory body plays a significant policy-making role, through providing recommendations to the GSA board on a broad array of issues, including the groundwater sustainability plan itself and how that plan would be implemented through regulations, projects, programs and funding. The Sonoma Advisory Body will advise the board on development and implementation of groundwater sustainability plan, regulations, fees, capital projects, programs, and community with stakeholder constituencies. | ||

| − | Each entity participating in the GSA would appoint one member of the advisory body. The GSA board would appoint seven additional members representing: | + | Each entity participating in the GSA would appoint one member of the advisory body. The GSA board would appoint seven additional members representing: two environmental representatives; two rural residential well owners; one business community representatives; two agricultural interests. And, Graton Rancheria, a tribe in the Santa Rosa Plain, would appoint a representative as well. |

Appointments to the advisory body are for two years and are made through a formal application process. Most entities preferred that the advisory panel be open to community members and staff representatives. Meetings are subject to public process transparency laws in California, and are open to public attendance as per the Brown Act. Decision-making for this body will be made under the protocols established by its charter. | Appointments to the advisory body are for two years and are made through a formal application process. Most entities preferred that the advisory panel be open to community members and staff representatives. Meetings are subject to public process transparency laws in California, and are open to public attendance as per the Brown Act. Decision-making for this body will be made under the protocols established by its charter. | ||

| Line 319: | Line 337: | ||

''Achieving Sustainability:'' After forming the groundwater sustainability plans, the Santa Rosa Plain GSA and the Sonoma Valley GSA have 20 years to achieve sustainability. The law establishes seven metrics of sustainability, and the groundwater sustainability plan will quantify those metrics. Through the planning process, the plan will identify the steps necessary to achieve sustainability. Introducing tools to manage groundwater pumping is going to be instrumental to success and will not be easy. | ''Achieving Sustainability:'' After forming the groundwater sustainability plans, the Santa Rosa Plain GSA and the Sonoma Valley GSA have 20 years to achieve sustainability. The law establishes seven metrics of sustainability, and the groundwater sustainability plan will quantify those metrics. Through the planning process, the plan will identify the steps necessary to achieve sustainability. Introducing tools to manage groundwater pumping is going to be instrumental to success and will not be easy. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|Summary=Following three years of severe drought -- the driest recorded period in the century and a half since the state began recording rainfall -- California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014 (SGMA) to create a statewide framework for groundwater regulation. This legislation called for local agencies to form Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSA) for 127 priority groundwater basins by 2017, develop groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) by 2022, and achieve sustainability within 20 years. Each GSA has the significant challenge and opportunity to develop a GSP and prevent “undesirable results” of chronic groundwater overdraft while considering the interest of “all beneficial uses and users of groundwater.” | |Summary=Following three years of severe drought -- the driest recorded period in the century and a half since the state began recording rainfall -- California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014 (SGMA) to create a statewide framework for groundwater regulation. This legislation called for local agencies to form Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSA) for 127 priority groundwater basins by 2017, develop groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) by 2022, and achieve sustainability within 20 years. Each GSA has the significant challenge and opportunity to develop a GSP and prevent “undesirable results” of chronic groundwater overdraft while considering the interest of “all beneficial uses and users of groundwater.” | ||

| Line 337: | Line 353: | ||

|Topic Tag=SGMA | |Topic Tag=SGMA | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | |Refs=Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2017). Gross Domestic Product by State - First Quarter of 2017. Retrieved from https://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/regional/gdp_state/2017/pdf/qgsp0717.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | California Department of Water Resources. (February 2015). California's Most Significant Droughts: Comparing Historical and Recent Conditions. Retrieved from http://www.water.ca.gov/waterconditions/docs/California_Signficant_Droughts_2015_small.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | California Water Plan Update 2013. Vol. 3.16. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.water.ca.gov/waterplan/docs/cwpu2013/Final/Vol3_Ch16_Groundwater-Aquifer-Remediation.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | California Water Resources Control Boards. (January 2013). Communities That Rely On A Contaminated Groundwater Source for Drinking Water: State Water Resources Control Boards Report to the Legislature. Retrieved from https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/gama/ab2222/docs/ab2222.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | Johnson, Renee and Betsy A. Cody. (June 2015). "California Agricultural Production and Irrigated Water Use." Retrieved from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44093.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kunkel, K. E., L. E. Stevens, S. E. Stevens, L. Sun, E. Janssen, D. Wuebbles, and J. G. Dobson. (2013). Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment: Part 9. Climate of the Contiguous United States. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Technical Report NESDIS 142-5. Retrieved from https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/asset/document/NOAA_NESDIS_Tech_Report_142-5-Climate_of_the_Southwest_U.S.pdf | ||

| + | |||

| + | M. A. Maupin, et al. (2014). "Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2010,” USGS Circular 1405. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Moran, Tara, Janny Choy, and Carolina Sanchez. (2014). The Hidden Costs of Groundwater Overdraft. Retrieved from http://waterinthewest.stanford.edu/groundwater/overdraft | ||

| + | |||

| + | Monterey County Farm Bureau. (2015). Facts, Figures, and FAQs. Retrieved from http://montereycfb.com/index.php?page=facts-figures-faqs | ||

| + | |||

| + | Richtel, Matt. (June 2015). California Farmers Dig Deeper for Water, Sipping Their Neighbors Dry. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/07/business/energy-environment/california-farmers-dig-deeper-for-water-sipping-their-neighbors-dry.html | ||

| + | |||

| + | USDA Farm and Ranch Irrigation Survey. (2013). Retrieved from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44093.pdf | ||

|External Links= | |External Links= | ||

|Case Review={{Case Review Boxes | |Case Review={{Case Review Boxes | ||

Latest revision as of 14:34, 13 November 2017

| Geolocation: | 38° 34' 40.6398", -122° 59' 19.7948" |

|---|---|

| Total Population | .502502,000,000 millionmillion |

| Total Area | 45804,580 km² 1,768.338 mi² km2 |

| Climate Descriptors | Humid mid-latitude (Köppen C-type), Dry-summer |

| Predominent Land Use Descriptors | agricultural- cropland and pasture, agricultural- confined livestock operations, conservation lands, forest land, urban |

| Important Uses of Water | Agriculture or Irrigation, Domestic/Urban Supply |

| Water Features: | Sonoma Valley Groundwater Subbasin, Petaluma Valley Groundwater Subbasin, Santa Rosa Plain Groundwater Subbasin, Russian River, Sonoma Creek |

| Riparians: | California (U.S.) |

Contents

[hide]- 1 Summary

- 2 Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

- 2.1 History of the California Groundwater Supply

- 2.2 Background on Sonoma County Groundwater

- 2.3 GSA Stakeholder Issue Assessment

- 2.4 Recommendations

- 2.5 Outcomes and GSA Governance Structure

- 2.6 Future Challenges and Solutions

- 3 Issues and Stakeholders

- 4 Analysis, Synthesis, and Insight

- 5 Key Questions

- 6 References

Summary

Following three years of severe drought -- the driest recorded period in the century and a half since the state began recording rainfall -- California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014 (SGMA) to create a statewide framework for groundwater regulation. This legislation called for local agencies to form Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSA) for 127 priority groundwater basins by 2017, develop groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) by 2022, and achieve sustainability within 20 years. Each GSA has the significant challenge and opportunity to develop a GSP and prevent “undesirable results” of chronic groundwater overdraft while considering the interest of “all beneficial uses and users of groundwater.”

Beginning in 2015 shortly after the legislation, groundwater sustainability agency formation in Sonoma County, California, involved mediating agreements on governance for three emergent groundwater agencies, including legal structure, governing board structure, voting, initial funding, and public advisory component in three priority basins under California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.

The Consensus Building Institute (CBI), an impartial mediation and facilitation services organization, facilitated discussions among staff of agencies eligible to serve as the GSA and workshops with interested stakeholders and the public to identify agreements on GSA formation. At the outset of this effort, CBI conducted an issue assessment with eligible agencies and stakeholders and conducted a joint evaluation with Sonoma County staff to assess issues and design a decision-making framework on the agency formation process. Public agency staff and CBI designed and implemented a countywide community engagement plan and held nine public workshops to solicit input and build widespread support and understanding. Toward the end of the process, CBI convened a meeting of elected officials from 9 public agencies to resolve final conflicts on voting and representation for GSA formation.

The agreement included the legal structure, board composition and selection, voting, and funding for the agency formation process. The newly formed agency, the Santa Rosa Plain Groundwater Sustainability Agency, will regulate groundwater. The process achieved success for a variety of reasons: the public workshops were instrumental to broadening input to staff-centered discussions; the robust advisory process gave non-governmental actors a voice to contribute to decision-making; and the provision to allow newly formed entities to automatically join the governing board.

Natural, Historic, Economic, Regional, and Political Framework

History of the California Groundwater Supply

Regional Outline

Geography

Sonoma County lies in the North Coast Ranges of California, northwest of the San Francisco Bay Area region.

Economy and Groundwater

California is the most populous state in the country with almost 40 million residents and has the single largest state economy with a GDP of 2.67 trillion USD. This means it makes up 14.1% of US GDP, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA 2017). Access to a water supply has been essential to the functioning of many of key state industries as well as its populous urban centers. California also has an extremely variable climate: dry years were common throughout the 20th century and could extend into a period of several years, such as the eight-year drought of Water Years (WY) 1984 to 1991 (DWR 2015; Chap. 3). During these extended dry periods, state agencies restricted water allocations to urban and agricultural water contractors and were forced to rely heavily on groundwater access, reservoir storage, and water sharing schemes.

California ranks as the leading agricultural state in the United States in terms of farm-level sales. In 2012, California’s farm-level sales totaled nearly $45 billion and accounted for 11% of total U.S. agricultural sales (Johnson & Cody 2015). Given frequent drought conditions in California, there has been much attention on the use of water to grow agricultural crops in the state. Depending on the data source, irrigated agriculture accounts for roughly 40% to 80% of total water supplies (Johnson & Cody 2015). Such discrepancies are largely based on different survey methods and assumptions, including the baseline amount of water estimated for use (e.g., what constitutes “available” supplies). The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimates water use for agricultural irrigation in California at 25.8 million acre-feet (MAF), accounting for 61% of USGS’s estimates of total withdrawals for the state (Maupin et al. 2014).

USDA’s 2013 Farm and Ranch Irrigation Survey reports that, nationally, California has the largest number of irrigated farmed acres compared to other states and accounts for about one-fourth of total applied acre-feet of irrigated water in the United States. Of the reported 7.9 million irrigated acres in California, nearly 4 million acres were irrigated with groundwater from wells and about 1.0 million acres were irrigated with on-farm surface water supplies (USDA 2013). Water use per acre in California is also high compared to other states averaging 3.1 acre-feet per acre, nearly twice the national average (1.6 acre-feet per acre) in 2013 (USDA 2013). Available data for that year indicates, of total irrigated acres harvested in California, about 31% of irrigated acres were land in orchards and 18% were land in vegetables (USDA 2013). Another 46% of irrigated acres harvested were land in alfalfa, hay, pastureland, rice, corn, and cotton (USDA 2013).

Climate and Groundwater

Drought periods are a trend which will increase in frequency and severity as a result of anthropogenic climate change: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that precipitation events, especially snowfall, in the southwestern United States will become less frequent or productive in the future (Kunkel et al. 2013). These changes in surface water availability may further increase the role of groundwater in California’s future water budget: historically, California has relied on groundwater to supplement other backstops like reservoirs. Therefore, the California Water Plan emphasizes that the protection of groundwater aquifers and proper management of contaminated aquifers is critical to ensure that this resource can maintain its multiple beneficial uses (California Water Plan 2013).

The California Department of Public Health estimates that 85 percent of California’s community water systems serve more than 30 million people who rely on groundwater for a portion of their drinking water supply (California Water Boards 2013; 7). Because of significant current and future reliance on groundwater in some regions of California, contamination or overdraft of groundwater aquifers has far-reaching consequences for municipal and agricultural water supplies. Sonoma County is a groundwater-dependent area, regularly drawing more than 70 percent of its water from wells to meet demand for 260 million gallons a day, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Agriculture consumes nearly 150 million gallons, about 60 percent of the total. California’s reliance on groundwater increases during times of drought, offsetting surface water demand from municipal, agricultural, and industrial sources.

A 2014 Stanford "Water in the West" study summarizes the often-overlooked impacts of groundwater overdraft. Direct impacts include a “reduced water supply due to aquifer depletion or groundwater contamination, increased groundwater pumping costs, and the costs of well replacement or deepening” (Moran et al. 2014). Less obvious are the indirect consequences of groundwater overdraft, which include “land subsidence and infrastructure damage, harm to groundwater-dependent ecosystems, and the economic losses from a more unreliable water supply for California” (Moran et al. 2014). In coastal groundwater basins, overdraft of aquifers can result in seawater being drawn in. This saltwater intrusion contaminates the water supply and requires expensive remediation. Groundwater overdraft can also lead to diminished surface water flow (affecting ecosystem services), degraded water quality and attendant health problems, and increased food prices.

Although there is little data available on total damages, costs associated with overdraft mount in a variety of ways, some more obvious and immediate than others. Accessing deeper and deeper aquifers is costly because drilling and pumping groundwater are expensive. The electricity needed to run pumps is a significant and obvious expense: in 2014, the statewide drought is estimated to have cost the agricultural industry $454 million in additional pumping costs alone (Moran et al. 2014). Remediation of water quality and land subsidence is an endeavor where costs accumulate over time. Local water agencies must undertake dramatic measures to stem saltwater intrusion into aquifers, like running pipes from distant surface water sources to inject into the ground. Land is subsiding at more than a foot a year in some parts of the state as a result of groundwater overdraft and aquifer compaction. In some California valleys like San Joaquin, well over a billion dollars of associated damages have accumulated over several decades as land buckles under infrastructure and buildings (Moran et al. 2014). Rural landowners and small-scale farmers can be disproportionately affected by overdraft as they have less financial capital to dig new or deeper wells (Richtel 2015).

Politics and Governance

Groundwater Management Act

Since the early 1990s, existing local agencies have developed, implemented, and updated more than 125 Groundwater Management Plans (GWMP) using the systematic procedure provided by the Groundwater Management Act, Sections 10750‐10755 of the California Water Code (commonly referred to as AB 3030). AB 3030 allowed certain defined existing local agencies to develop a groundwater management plan in groundwater basins defined in California Department of Water Resources (DWR) Bulletin 118.

The twelve potential components of a Groundwater Management Plan, as listed in Water Code Section 10753.8, include:

- Control of seawater intrusion.

- Identification and management of wellhead protection areas and recharge areas.

- Regulation of the migration of contaminated groundwater.

- Administration of a well abandonment and well destruction program.

- Mitigation of conditions of overdraft.

- Replacement of groundwater extracted by water producers.

- Monitoring of groundwater levels and storage.

- Facilitating conjunctive use operations.

- Identification of well construction policies.

- Construction and operation by the local agency of groundwater contamination cleanup, recharge, storage, conservation, water recycling, and extraction projects.

- Development of relationships with state and federal regulatory agencies.

- Review of land use plans and coordination with land use planning agencies to assess activities which create a reasonable risk of groundwater contamination.

(Monterey County GWMP 2006; 1)

However, under the previous law (AB3030), no new level of government is formed and action by the agency is voluntary, not mandatory. Senate Bill 1938 enhanced the process slightly and added technical components that are required in each plan in order to be eligible for groundwater related DWR grant funding.

Assembly Bill 359, signed into Water Code 2011, added further technical components and modified several groundwater management plan adoption procedures. GWMPs were not required to be submitted to the California DWR under the Groundwater Management Act. AB 359 placed new requirements on agencies concerning the submittal of GWMP documents and on DWR to provide public access to this information. GWMPs may still be developed in low-priority basins as they are not subject to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (2014)

California’s historic groundwater management legislation, passed in 2014 after the driest three-year period recorded in state history, requires that groundwater be managed locally to ensure a sustainable resource well into the future. This legislation, a package of three bills (AB 1739, SB 1168, and SB 1319) known as the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), prioritizes groundwater basins in significant overdraft to move forward first. SGMA requires that such areas first identify or form an agency or group of agencies to oversee groundwater management, then develop a plan to to halt overdraft and bring basins into balanced levels of pumping and recharge by 2020 or 2022, depending on water supply condition. Beginning January 1, 2015, no Groundwater Management Plans can be adopted in medium- and high-priority basins in accordance with the SGMA. Existing GWMPs will be in effect until Groundwater Sustainability Plans (GSPs) are adopted in medium- and high-priority basins.

For the first time in California history, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act provides local agencies with a framework for local, sustainable management of groundwater basins. The State of California has designated 127 basins in the state as high- or medium-priority based on population, irrigated acreage, public supply well distribution, and other variables. Prioritized basins, which includes the three Sonoma Valley sub-basins, must create groundwater sustainability plans by 2022. The California Department of Water Resources Bulletin 118 is a report that defines the basin boundaries.